Expropriating the rich

There are many out there who insist that we really must, just must, expropriate the rich. We’ve even seen one buffoon state baldly “We must tax the rich because they are rich”. It’s also noted, a la M. Piketty, that the rich have been expropriated. Unfortunately, he gets the mechanism entirely wrong.

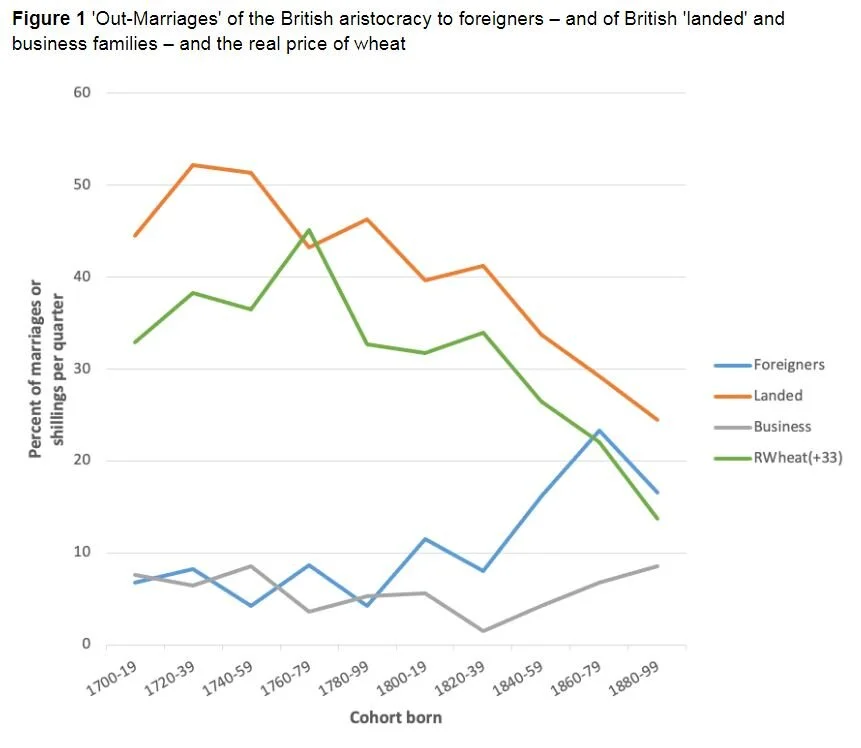

The premise of my recent paper (Taylor 2021) is that the rapid decline in British agricultural prices in the last quarter of the 19th century, which shrank not only the income of aristocratic landed estates but also the income of ‘commoner’ (i.e. non-aristocratic) families who owned land, led to a significant proportion of male aristocrats marrying American heiresses with rich dowries as substitutes for the traditional source – namely, brides from British families with landed estates but no titles.

British agricultural prices began their drop in the mid-1870s for several reasons, from the development of US railroads and prairies to the advent of steamships, all of which led to the UK market being flooded with cheap prairie wheat.

Agricultural land prices declined precipitately as a result of those changes. One marker of how much they did is that by the 1920s the income from an agricultural estate would not even maintain the buildings which the prices of a century before had been able to build.

But by the timing of this we can see that it wasn’t wars, taxation or government action - with one exception - that led to this expropriation of the landed classes. M. Piketty is wrong in his analysis. It was that technological change, the flood first of produce from the US and then, in the 1890s, from the Ukraine, that did. The government action was the revocation of the Corn Laws in 1846 which meant government got out of the way and allowed the technological change to so alter the wealth distribution. Those conservatives opposing the change were in fact right, the common man gaining cheaper bread would change their fortunes.

This is something that has a lesson for today’s social justice warriors. Technological change is what promotes social mobility by altering the value of assets and income streams. In a time of technological change one cannot remain at the top of the societal pile by simply sitting, lumpen, on the useful assets of the previous economic model. In our current day we could note that it is the geeks inheriting the earth but their time will pass too, as did that of merely owning land.

That lesson being that those who desire more of that social mobility need to support the system which best promotes technological change - that is, of course, free market capitalism. Those those arguing for social mobility need to be arguing for more free market capitalism and a lot less protection of the incomes and assets of the current generation of top dogs.

Oh, and that lesson of how to actually deal with those entrenched asset holdings. The way to expropriate the rich is to compete it out of them, not confiscate it.

Be careful of conflating pay and living conditions

While making a case - which we’re not commenting upon right here and right now - against raising national insurance this point is made:

Nor have most people enjoyed a long period of steadily improving living standards, of the kind that might make them more inclined to be generous. Real pay, immediately prior to the pandemic, was still below the peak it reached under the last Labour government. Conservative-led governments delivered a lost decade for earnings, especially for the young.

The is both a logical and empirical error. Real pay and living standards are not the same thing. We may indeed say that they should be, for what we hope to measure and discuss as real pay is those living standards of those who gain that pay. But that’s not how it actually works out.

Real pay is derived from adjusting nominal pay by the inflation rate. This rather leaves out much of the effect of technological advance.

Assume, for the moment, that the peak in nominal, and by this calculation real, pay was in 2007, before the Grand Crash. That also the year of introduction of the iPhone, the first mass market smartphone. Even if nominal pay, or real as adjusted by the general inflation rate, has remained static does anyone really believe that a world with more smartphones (in the UK at least) than people now as opposed to none then has had static living standards? Or broadband, which has risen in average speed from some 2 Mbits to 90 or so. Streaming was hardly even a thing back then, nor was mobile internet. Facebook only went to general availability in 2006. So too did Twitter launch that year - for all that second may or may not be an addition to living standards.

The idea that living standards have been static since 2007 is absurd.

As to why, inflation calculations deal badly with new tech. Those two social media sites, being free, aren’t included at all nor are they in GDP. But inflation is calculated from the consumer basket - things that lots of people do in proportion. Which, by definition, doesn’t include things that no one does, nor what few people do as a new technology starts out. Only when many people are doing it does it enter the basket and become part of inflation. But that’s also after the first mass reduction in price which accompanies the change from rich man’s toy to mass acceptance which is the path of all new techs.

It’s simply innate to inflation calculations that they don’t deal well with new tech.

One set of estimates- probably the best we’ve got - says that WhatsApp is worth $600 a month to users, Facebook $50 and Search engines and free email (so, Google) $18,000 a year.

Or, as we might put it, the reason that real pay isn’t reflecting the rise in living standards these past two decades is because we don’t measure the rise in real pay properly. After all, it is supposed to be how much do we get for an hour of our labour? If that’s rising then so is real pay.

The next sector for international trade - cannabis

The Guardian tells us of how aged grandmothers, trying to bring up their AIDs orphaned grandchildren, illegally grow marijuana in the mountains of Swaziland:

In Nhlangano, in the south of Eswatini (formerly Swaziland), the illegal farming of the mountainous kingdom’s famous “Swazi gold” is a risk many grandmothers are ready to take.

In what is known locally as the “gardens of Eden”, a generation of grandparents are growing cannabis, many of them sole carers for some of the many children orphaned by the HIV/Aids epidemic that gripped southern Africa.

The plots of marijuana are tucked away in forests in the mountains. Around one tiny village alone, the Guardian counted 17 fields of cannabis plants.

Noncedo Manguya is the breadwinner for her family of five grandchildren and two other children from her extended family, who were left in her care after the death of their parents. Manguya, 59, struggled to find a job or start a business and makes money by illegally growing marijuana, or dagga, that she sells on to dealers in South Africa.

This sounds like the sort of thing we ought to encourage. Not, we hasten to add, that we encourage there to be more orphans, or impoverished grandmothers who must break the law to feed them. Rather, the international trade which will make all of us better off.

We in the rich countries are finally - much too slowly but finally - getting sensible about cannabis. Both in the sense that we do own our own bodies and thus do, righteously, decide what goes into them and also in the more practical sense that prohibition simply doesn’t work. So, in fits and starts, medical, recreational, decriminalisation, legalisation, we’re changing the rules. But the one part that isn’t being changed is to allow international trade. Or at least that sensible policy is lagging domestic.

This is straight Ricardo, comparative advantage, even the laws of one price and all that. For as the UN reports (admittedly, old figures, 2006, 2008 and the like) marijuana herb is $40 in Swaziland, in not quite next country over, Malawi, it’s $10. In the UK from $5 to $15.

Except those Southern Africa prices are per kilogramme, the UK ones per gramme. A thousandfold price difference is the sort of thing international trade is made of. Legalising that would mean higher prices to the farmers, lower to consumers and human utility - not to mention pleasure - increases at both ends. And the region does already provide a significant portion of the global tobacco supply so the at least beginnings of the necessary infrastructure are there. There are also the beginnings of attempts to make this happen too.

We should do more to make this happen properly. Throw ourselves open to international trade here, to our own benefit and that of the producers.

The biggest opponents will be those who already try to grow cannabis in our own less amenable climate. Plus, there seems to be some infestation of the cannabis cheering classes with an anti-trade, anti-big business worldview. We do expect that thousandfold price difference to win out over such opposition, even if only eventually. And lets face it, we’re used to domestic producers being against international trade, aren’t we?

But let’s start right now. Whatever level cannabis consumption is at in any particular jurisdiction make the international production and trade in it subject to exactly the same rules as any domestic. Prices will tumble at our end and grandmothers will feed their orphans better at the other.

Sounds like a plan.

The purest nonsense about American wealth inequality

The latest bemoaning of wealth inequality in the US:

The shocking racial wealth gap between families, and its impact on Black and Hispanic kids, is revealed in groundbreaking new research by scholars on US inequality. It shows that the basic wealth levels of families from different racial and ethnic backgrounds have diverged to such a stark degree in the past three decades that the future prospects of children from lower-wealth groups are likely to be grossly compromised.

In 2019, the median wealth level for a white family with children in the US was $63,838. The same statistic for a Black family with children was $808.

It’s the purest nonsense. The full papers are here. The crucial error is here.

National levels of income inequality have long been shown to be shaped by labor-market institutions and welfare states

In their measurements of wealth inequality they, determinedly and in common with other wealth studies, refuse to incorporate the effects of welfare states. Just to remind, yes, the United States does have one of those even if it’s a little different.

As an example, and not one that specifically applies to families with children, the capital value of Social Security as a retirement income can be put in the $300,000 to $600,000 range - depends upon full or minimal benefits, expected lifespan, assumed discount rates and all that. Being naughty and extreme with those numbers, a racial wealth gap of $363,838 to $300,808 looks a great deal less alarming.

Now add in Medicare (of more interest to those in retirement of course), Medicaid, free schooling, unemployment insurance, the EITC and Section 8 (both of a great deal more interest to families with children, as with the schooling) the child tax credit and on and on up to and including free cellphones.

Their measurement of wealth inequality is before all of those things done which reduce wealth inequality. As a decision making tool it is therefore valueless for what is desired before deciding whether to do more, less or nothing is what is the situation after what is already done?

Further, don’t forget one rather important point. If everything government does which reduces wealth inequality is to be disregarded then it’s not a problem that can be solved by government, is it? For we’ll have to disregard the effects upon wealth inequality of what government does.

We do so enjoy the New Economics

The world has entirely changed, so we’re told in The Guardian:

Their problem is that many of the issues exacerbated by the pandemic, such as wage stagnation, precarious work and rising inequality are not bugs in an otherwise well-functioning system, but inevitable outcomes of the way that western economies are now organised. So a business-as-usual approach simply won’t work. Much more fundamental change is needed.

Global neoliberalism hasn’t produced much growth so we must have a different system that produces growth. Well, OK, not much growth except for the greatest reduction in absolute poverty in the history of our species.

Still we must have change:

Unlike his predecessors, Biden is pursuing large-scale public spending and taking advantage of ultra-low interest rates to borrow for infrastructure investment. His stimulus plans target the climate crisis while creating green jobs and expanding health, education and childcare – the “social infrastructure” that is essential to the economy but has often been ignored by mainstream economists.

That’s more generally called current spending rather than investment in infrastructure. But, change!

This was followed by long years of austerity and slow growth, stagnating wages, stalling productivity and extreme inequality.

We must have that more growth!

As long as low interest rates keep the cost of borrowing affordable, and borrowing is used to fund investment (which raises future national income and therefore brings in more taxes), the ratio of debt to GDP will ultimately fall.

Not just will the growth pay for all these lovely things, we need the growth in order to pay for the lovelies.

We’re really pretty sure this has all been tried before. Sweden quite famously retreated from it a few decades back. But still, the true glory of the New Economics argument is here:

Above all, many are starting to realise that economic policy needs to end its fixation with growth. Growth was never the only aim, but economists long assumed that it would solve most other problems. It’s now clear this was never the case. New ideas for “post-growth” economics are emerging, which focus on environmental sustainability, reducing inequalities, improving individual and social wellbeing and ensuring the economic system is more resilient to shocks.

As well as complaining that global neoliberalism doesn’t produce growth, therefore we need more government to have more growth and, also, we must invest to get the more growth to pay for the investment, we don’t need and shouldn’t have growth anyway.

Believing entirely contradictory things is oft taken as a sign of a certain mental fragility and we used to have comfy places for people to recover from such. That system was abandoned but we were unaware that it was replaced by positions in economics departments:

Michael Jacobs is professor of political economy at the University of Sheffield, and managing editor of NewEconomyBrief.net

Ah, that’s right, political economy isn’t economics is it? Nor, apparently, is it constrained by basic logic.

The British chip industry benefits from the Cowperthwaite approach

Sir John Cowperthwaite was sent out to aid in running Hong Kong after WWII. So the story goes it took him some months to get there and found it thriving without his guiding hand. Therefore, he concluded, his job was to make sure this continued by not allowing anyone else to try to be that guiding hand.

Asked what the key thing poor countries should do, Cowperthwaite once remarked, "They should abolish the office of national statistics." He refused to collect all but the most superficial statistics, believing they led the state to fiddle about remedying perceived ills, thus hindering the working of the market. This caused consternation: a Whitehall delegation was sent to find out why employment statistics were not being collected, but the financial secretary literally sent them back on the next plane.

So it is said, he refused even to collect, or to allow to be collected, GDP statistics on the grounds that “some damn fool will only want to do something with them.”

Hong Kong remained, until just very recently, the most classically liberal free market economy in the world and thereby became one of the richest.

Which brings us to the British computer chip industry:

Britain’s first-class chip industry must be protected

Indeed so.

This century, Bath and Bristol, the latter home to Inmos’s design team, have spawned successful conventional microprocessor companies such as Picochip (sold to Intel) and the latest tech Unicorn, Graphcore. British chip companies have had to be resourceful – our most successful today is Arm, which was unable to secure funding for a fab, so instead pioneered the model of licensing its designs.

Today a new and exciting nationwide ecosystem is emerging in the new field of advanced, post-Silicon electronics, components with science fiction-like properties, but an awful name: “compound semiconductors”.

.....

For commercial success, you need three things near each other, says Dr Andy Sellars of the Compound Semiconductor Applications Catapult: researchers, the chip design teams, and the fabs, and Britain has all three.

“We’re world leaders in this niche,” says Rupert Baines, formerly chief executive of the British chip company UltraSoc, which made a successful exit when it was acquired by Bosch for £150m last year.

...

So why is SW1 so oblivious to it?

The contrast is made between this current success, where SW1 does not just leave the industry to its own devices (sorry) with a policy of benign neglect but one of active ignorance, and the failures such as Inmos when government was more deeply involved in subsidy and direction.

Which leads to the obvious point that protecting the industry should be done by the Cowperthwaite method. It is the absence of government or political involvement that has led to the thriving and world class sector. The task is therefore to continue the policy of not allowing a guiding hand.

Policy becomes obvious. Not that we’re supposed to use quite such incendiary language and we do mean this in a metaphorical sense only, but protecting Britain’s chip industry is best done by shooting any politician who even so much as expresses an interest let alone has suggestions for policy.

Fiddling while Rome burns

39 Victoria Street,

London SW1

“Humphrey.”

“Yes, Minister?”

“You seem to be concerned that the 2014 Care Act is not part of everyone’s holiday reading. Is that why you have issued a ‘List of changes made to the Care Act guidance’?”

“Well, we like to keep up to date, Minister.”

“Isn’t 2014 a bit passé?”

“Study guides are still being produced for Virgil’s Aeneid. Great works of fiction, I mean great literature needs to be re-interpreted as times change.”

“I think we would rather know, Humphrey, what the Care Act was supposed to achieve and whether it did so.”

“Indeed. In 2016 we produced no less than 12 ‘Factsheets’ which review the Act.”

“Yes, but none of them address what the Act was supposed to achieve nor whether anything changed.”

“We only have to specify, Minister, what should happen and leave it to local authorities to make sure it does.”

“Have we ever actually enforced the Care Act?”

“As we are not responsible for local authorities; the Ministry of Housing is, we have no records on that. We do know that eight councils in the last year applied a moratorium on the Care Act due to workforce shortages and the pandemic.”

“Does that mean all local authorities could claim a moratorium, given the nationwide carers shortfall?”

“Very possibly, Minister.”

“So our response to that is not to do anything substantial but just to fiddle about with our guidance on how to interpret an Act which, so far as we know, has proved completely useless?”

“I know it will not accompany you to the beach, Minister, but August is a good month for tidying things up. And the 2016 Factsheets are also helpful guides as to desired outcomes.”

“One example of something that we should address, Humphrey, came up on the Today programme on Monday. Apparently, those staff members in care homes in November still refusing Covid vaccination must be sacked but if the same people are working in NHS hospitals, they can carry on infecting all and sundry. The irony is that care home deaths are now rare whereas hospitals are dangerous places to be.”

“Minister, really! Care home workers are not employees of ours, so we can set the rules. NHS staff, however, are our employees and the unions would object if we made jabs a condition of employment.”

“A ridiculous argument, Humphrey, but let’s look at the actual changes you have made to the Care Act guidance.”

“The new paragraph 2.60 is exactly the same as the one it replaces, except the words are in slightly different order. Paragraph 6.71 has been split into two separate paragraphs 6.71 and 6.72. Paragraph 6.121 is also basically unchanged except it is now eight sub-paragraphs of outcome criteria for eligibility, rather than 16.”

“Humphrey, is fiddling about like that really useful?”

“Meat and drink to professional civil servants.”

“Paragraph 6.128 has moved from ‘Outcomes’ ‘Wellbeing’ and paragraph 8.34 now distinguishes ‘short term’ from ‘temporary’ residents of care homes. That is an important distinction.”

“Your staff must have been working long hours to achieve these results, Humphrey.”

“Indeed we have – and during August too, when the Foreign Office was spread across the Mediterranean.”

“Should I also be impressed by making the maximum interest rate payable on deferred payment agreements more specific? Paragraph 9.64 sets it at 0.15% above the market gilts rate. Rather superciliously, it spells out the arithmetic: ‘for example, gilt rate 1% plus 0.15% equals a maximum interest rate of 1.15%’”

“Thank you, Minister. We thought that even an other-worldly judge should be able to grasp that.”

“Humphrey, I was rather puzzled by the new para 18.5 which is identical to the old one. It has the same 147 words in the same order.”

“After considerable thought, consultation and analysis, Minister, we felt that the original could not be improved. Surely we deserve credit for that.”

“Well, I had to read it several times before I realised how clever it was.”

“’Chapter 19 has been updated to include our position on where people live, following the Supreme Court judgment in the case of Cornwall Council v Secretary of State for Health and Others (Cornwall).’”

“Humphrey, really! That tells us nothing. How do we decide where people live and how has that changed?”

“We have not yet actually reached a conclusion on that matter, Minister. We had to leave ourselves with work to do.”

“The last chapter certainly gives the flavour of all this. The only change is replacing 2016 by 2020 as the date from which the guidance applies and it makes no difference anyway.”

“I hope I do not detect a note of dissatisfaction, Minister. That could be construed as bullying.”

“What you are detecting, Humphrey, is astonishment that our department can be wasting time on this drivel, when we should be sorting out the chaos in our whole adult social care system. We have too few carers, and they are not paid or recognised enough. The population is growing and the numbers of young and old needing care are growing even faster. No one has sorted out how the costs of caring for the elderly should be split between the taxpayer and those being cared for, or between central and local government. A substantial rise in homelessness is predicted, boosted by the inflow of refugees, and yet, so far as I know, we have no plans to address that either. No doubt you will tell me that that is the Ministry of Housing’s job. But when I get volunteered onto the Today programme by Number 10, I’m going to have to explain why we are fiddling around with the wording of our Care Act guidance when we should be addressing the big issues.”

”I am sure you will do that very well, Minister.”

But government appointing their own is the point of having elections

We’re fully in favour of Katherine Birbalsingh:

Katharine Birbalsingh, the founder of the “super-strict” London-based Michaela community school,

We’d not say “super-strict” we’d say she has founded and runs a super-successful educational establishment. By which we mean that it educates the pupils of it, no other definition of success really comes usefully to mind.

However, the bit in this story that interests is this:

Birbalsingh’s appointment would raise eyebrows, following previous claims that the government was placing hand-picked allies into key public roles.

This is rather the point of having elections, no? The people, that’s you and us and me, decide that the path of government has become unrighteous and we’d like a change. If enough of us do so at an election then the change of government does happen. The manner by which the path then changes is that government appoints people it agrees with, likes, to those key public roles.

If those key roles, even after that change in government, continue to come from the same previously approved ideological class then what value that democratic decision?

If every victims’ commissioner, child poverty commissioner, social mobility commissioner, online hate commissioner and Uncle Tom Cobbleigh commissioner continues to come from the same small pool of those who agree with the ancien regime then how much overthrowing - in accordance with that democratic vote - of the anciens is going to happen?

The answer being, of course, not a lot. Which is why these reports of unnamed eyebrows being raised. To try to fend off that change in defiance of the expressed views of us mere peasantry out here. Don’t we know that whoever we vote for, whatever it is that we desire, we should continue to do what we’re told by the same establishment that we’ve rejected?

The entire point of elections is to be able to change who rules us. That includes who gets appointed to key public roles.

Fortunately we know how to solve this problem - global neoliberalism

Kenan Malik tells us that global inequality is just ridiculously high and something ought to be done about it. He’s right of course:

The 30 poorest countries in the world, with a combined population of almost a billion, have vaccinated on average barely 2% of their population. In the Democratic Republic of the Congo the figure is 0.1%, in Haiti 0.24%, in Chad 0.27%, in Tanzania 0.36%. “Living with the virus” will mean something very different in such countries than it will in the west.

There is though a problem with this observation - why is this true? Not that it is true, but why?

For the same inequalities exist for other forms of health care. The same inequalities exist in the calories on the table each evening, in the lack of or existence of holes in the ceiling that let the rain in and the number of shirts available to clothe nakedness. The reason being that some places and people are very much poorer than others.

We do not face simply a vaccine inequality, but a more general economic one. That more general problem being the one to solve as each of the individual inequalities will close as we do that. As Robert Colville points out:

Indeed, when the UN millennium summit set a target of halving extreme poverty (an income of below $1.25 a day) by 2015, it was through the opening of developing countries to global trade that this was achieved five years early. It was growth led by a mixture of western consumerism and developing world industrialisation, not “degrowth”, that transformed lives for the better in the poorest nations.

That being the great truth of these recent decades. It’s the one large and important truth of recent decades in fact:

If you care about people, the economic growth over the last generation is one of the most important stories in all 5,000 years of human civilization. Every economic issue discussed in our recent election cycle pales in comparison.

....Our world has, over your lifetime, undergone the greatest reduction in poverty and misery in human history. Heck, more people have been lifted out of poverty over that time than in all the rest of human history.

We can see this in the tabulations of how many poor there are out there. We can also note what it was that caused this. As Colville is far too polite and refined to point out in these words it was that globalised neoliberalism red in tooth and claw. The gross exploitation by the capitalist classes of the consumers of the world in pursuit of profit. These are the things which have reduced that absolute and abject poverty. In order to do more such reduction we need to do more allowing of those powerful economic forces - the forces which achieve the goal it is at least claimed we desire.

Global inequality has indeed fallen these recent decades as a result. And, by the very nature of these things, as that does then all the more specific inequalities - of gender, of access to contraception, vaccines, health care, education, nutrition, of life - reduce too. For that’s what economic growth is, the ability to have more of these things.

To reduce inequality further we need to have more of what has been reducing inequality - globalised neoliberalism.

We already have a Department for the Future

“The Department of the Future would set in motion a realignment of priorities in all aspects of society,” proposes geology professor Marcia Bjornerud in her compelling book Timefulness. “Resource conservation would again become a core value and patriotic virtue. Tax incentives and subsidies would be rebalanced to reward long-term stewardship over short-term exploitation.”

We already have such a Department for the Future. It’s called that capitalist free market out there.

For example, which organisations have the longest planning timelines? It’s not governments, run as they are by politicians whose horizons extend just beyond the next press conference all the way to the next election. It’s almost certainly the oil and mining companies who regularly plan and make 50 year investments - that’s their planning horizon.

We can also approach this another way, the current value of an organisation is the net present value of all future income streams from it. In capital markets concentration upon short term gains is also known as capital destruction and valuations do fall as a result.

Perhaps the only human institution that plans longer term than corporations is the family. By a likely time of death these days one might well have met one’s own great grandchild - a pretty direct link to thinking about another 80 years into the future when they’re likely to still be going.

But say that this isn’t enough, that we must reorder society once again to gain that longer term view. That means the abolition of inheritance taxation. Remove economic resources from that terribly short term politics and retain it in the human institution with the longest planning horizon. We can even test this. The Ottoman Empire had, over large economic resources at least, effectively a 100% inheritance tax. Everything belonged to the Sultan and those lifelong leases granted to pashas and deys and viziers reverted upon their death. This is not a system which, to put it mildly, led to economic vibrancy over those generations.

That is, even if we were to think we should have a department of the future we’d not then locate it in government, our most short term institution of all.