Just how progressive should paying for social care be?

We look upon the current row about spending for social - by which everyone really means old age - care with a certain wonderment:

Sir Keir told MPs in the Commons that his party would support taxing wealth: “We do need to ask those with the broadest shoulders to pay more, and that includes asking much more of wealthier people, including in respect of income from stocks, shares, dividends and property.”

The Prime Minister and Chancellor’s plan to raise the dividend tax rate by 1.25 percentage points, another pillar of the Government’s package, amounted only to “tinkering and fiddling”, he claimed.

A tax on dividends is a tax upon income from stocks, shares and dividends Sir Keir.

But that’s just snark over a small part of the issue.

The current system is that those with wealth pay for their own social - old age - care. Those without wealth are subsidised from the general tax pot. A pot that is largely filled by those with both higher incomes and also wealth. Which, we submit, is a pretty progressive manner of funding that social - old age - care.

That is, if it’s a progressive system to pay for care that is desired then that’s what we’ve already got before any changes. So, why change it?

Capitalism and the solution to climate change

Not that we are endorsing this specific example of capitalism getting to grips with climate change, rather just a support of the underlying idea. Folks putting their own money where mouths are and getting on with attempting to solve a problem:

A British app that encourages people to give away excess food has raised $43m (£31m) from investors including German takeaway giant Delivery Hero.

Olio, founded in 2015 by Tessa Clarke and Saasha Celestial-One – whose second name was invented by her “hippy entrepreneur” parents – has 5m users who collect and distribute food that is going to waste in their neighbourhood.

The start-up has signed up deals with Tesco and Booker, which pay Olio to collect food near the end of its shelf life to give it away for free.

We’re not entirely sure that this is a particular problem but then that’s why central planning never does work - no one group of people can possibly know what all the problems are, let alone the solutions to them.

Ms Clarke said while she was a “card carrying capitalist”, she sympathised with Extinction Rebellion’s view that “time is running out” to tackle climate change.

We are pretty certain that time isn’t running out and that XR are entirely wrong about everything. However, we still support this base idea.

You’ve got an idea about how to make the world a better place? Go on then, do so. As and when you prove that you are doing so - making a profit being the signal that your output is worth more than your inputs put to alternative uses - then other greedy capitalists (sorry, that should read others following their own enlightened self interest) will copy you and the world will become a better place at an accelerating rate.

Capitalism providing both the incentive and the measuring rod, free markets the ability to try it all out.

Or, as both we and the IPCC have been saying for some decades now, free market capitalism is the way out of climate change assuming that the problem exists in the first place.

The Fabian Society fails Chesterton's Fence

Chesterton’s Fence is the idea that, if when walking in a field one encounters a fence, it is necessary to work out why a fence was built before concluding that the fence should be destroyed. We can also invert this and ask, when considering a new policy, whether we’ve had this before and if we did why did we stop doing so?

This is what the Fabian Society fails to do:

Hundreds of thousands of people would be guaranteed up to 80% of their earnings for a maximum of six months if they lose their job, under furlough-style proposals to overhaul the current unemployment benefit system.

Under the proposed scheme, people who have paid sufficient national insurance credits prior to losing their job would be eligible for payments of up to £460 a week – rather than the current job seeker’s allowance (JSA) of £75 a week for over 25-year-olds.

The scheme, proposed by the Fabian Society thinktank,

The thing being that we used to have this. From 1966 to 1982 in fact, then we stopped having it. We did look through the Fabian report and could see no mention of this - perhaps it is our speed reading at fault.

We can think of all sorts of reasons why it was stopped. Significant unemployment benefits do extend the period of unemployment. Costs might well be more than what a 1% rise in national insurance might cover. Folks might indeed start to wonder why people on higher incomes get more. But that’s not our point here.

The specific reasons why it might be a bad idea are this one thing over here. Far more important is this other over there that we used to have this then we stopped doing so. The first and most obvious thing to ask when proposing it again is, well, why did we stop having it? Failing to do that means that the entire suggestion must be ignored until they bother to do that most basic inquiry.

But then this is the Fabians, the future of the left from 1884 and having learnt little by experience since.

Shock horror! We do not all enjoy equal health

From time to time, the government bows to the view that, as we are not all equally healthy, the government should do something about it. According to the Department for Health and Social Care (DHSC), health inequalities cost the economy “around £100 billion a year”. Not unusually, the reasoning is fallacious: it is the ill health that costs the money, not the disparity. The NHS already focuses its resources on trying to make the sick healthy. If we were all equally unhealthy, the bill would be a great deal higher. The DHSC response, of course, is to set up yet another quango,The Office for Health Improvement and Disparities (OHID), which will tell us, yet again, not to smoke, to go easy on the booze, take more exercise and lose weight. There are no costs or performance measures. The OHID will have no effect but at least the government will be seen to have done something.

According to the WHO, the root causes of health disparities are “education, employment status, income level, gender and ethnicity”. The DHSC tells us that “health disparities across the nation [are] to be reduced by tackling [these] top risk factors for poor health”. That will be as transformative as four year-olds tackling the All Blacks.

The government needs to forget disparity and focus on improving the nation’s health overall. Has the DHSC considered, for example, whether the UK’s unique affection for the NHS is as much part of the problem as the solution? We can smoke, drink and get fat safe in the knowledge that the NHS will, mostly, protect us from the consequences at no cost to ourselves. Our GP may wave a warning finger and nanny state may run advertising to tell us to mend our wicked ways but the NHS will pick up the tab if we don’t.

In terms of healthcare quality, France and Italy come first and second with the UK 18th – not bad really. Italy is also the second healthiest country in the world (after Spain) with the UK 18th once again, but that does not tell us which countries have the lowest disparities. One would expect health and income disparities to correlate and on the latter the UK comes 104th [a high number means low disparity] out of 174 countries, next to Spain. The EU is comparable with the UK but the Nordic countries have slightly lower income disparity.

The French healthcare system expects some contribution, apart from taxes, from the unhealthy: “When you visit the doctor in France, the healthcare system will typically cover 70% of the fees and 80% of hospital costs. If you have a major illness, 100% of the expenses are covered………. the patient [pays] 1 EUR (1 USD), for example, per doctor visit.” Driving one’s car at excessive speed is not good for one’s life expectancy or that of others on the road but we are likely to pay a financial penalty for doing so. Irresponsible attention to one’s own health should attract penalties, not wholly free health care.

The disparity that does need attention is that between the NHS and social care. If one needs nursing due to a condition that’s no fault of one’s own, such as dementia, one is expected to pay for the care oneself or have one’s family do so. If, on the other hand, one occupies a hospital bed due to one’s own life choices, lung cancer for example, the state bears the cost. One’s life may be shortened but there is no financial penalty.

The nation’s social care problem will not be solved by giving more money to the NHS. Indeed, it may make both care and health worse. Social care “aggregate expenditure has declined in real terms by 8% between 2009/10 and 2015/16 in England” despite rising demand and huge increases for the NHS. We should use insurance to incentivise responsibility for our own healthcare and trim the NHS back to front line treatment and cure. It is astonishing that the insurance systems that have played such a big part in continental health and care systems barely exist here beyond BUPA-type health insurance that enables wealthier people, or those in high-level employment, to jump hospital waiting lists.

The Americans have given insurance too large a part; a balance between state (NHS and local authority) and private sector (insurance) health and care provision is needed. France and Germany have that roughly right; the UK does not.

As only about 20% of people used care homes at the last published census (2011), it is an ideal opportunity for insurance not least because the premium for those with healthy lifestyles would be lower than those for their more self indulgent cousins. “41% of residents in care homes fund themselves (self-funders) and 49% receive LA [local authority]-funding (around a quarter of these pay top-ups). Even for those receiving LA-funding, nearly all income, such as pensions, is offset against state contributions. The NHS also commissions nursing care services for people who have a primary health problem, around 10% of residents.” Of course, the problem would be that those who can least afford insurance are also those with the most need for it, i.e. the greatest health deprivation. Controversial as it would certainly be, the logical solution would be to increase social security benefits but then take the health and care premium from them. Practical solutions can be found on the continent.

Interestingly, whilst the care home population remained stable in the ten years to 2011 (290,000), the percentage dropped from 23% to 20%, possibly because of the funding difficulties.

The Association of British Insurers have talked with the government about this issue but, I was told, decided there was “no market for it.” In the 19th century there was no market for motor cars. A point which may have escaped them is that, far from being unfair, insurance is actually positive for reducing health disparities. If you are number 20 in the queue for a hip operation, and five people use private insurance to jump the queue, you are now number 15. Insurance is such a valuable tool to getting personal responsibility for one’s own health or late-in-life care that it should be tax deductible.

This blog makes four suggestions for reforming England’s health and care regimes:

The new disparities quango is either well intentioned, but muddled, thinking or a cynical application of political PR. Either way, it is an unhelpful distraction from the health and care reforms the country needs.

Private insurance already exists for health to a limited extent but not for late-in-life care. It should be encouraged for both, with tax deductibility, to incentivise healthier lifestyles through the premia.

The NHS does not need further large financial handouts but should be trimmed to front-line treatment and cure. Hospitals do not need layers of boards of different kinds nor should the NHS be allowed to take over social care via a mass of joint committees. The Centre for Policy Studies has found no evidence that integration improves outcomes.

Social care, per contra, does indeed need substantially more funding as well as a rise in status to rank alongside the NHS. That would also reduce the pressures on the NHS.

The significance of Labor Day

US Labor Day, September 6th this year, honours the works and contributions of labourers to the development and achievements of the United States. It is a Federal holiday and comes on the first Monday in September after a Labor Day weekend, a time of picnics and some parades. It marks the unofficial end of summer as the Northern hemisphere moves into autumn, and a time to enjoy the diminishing opportunities for outdoor barbecues.

Most European countries celebrate their Labour Day on May 1st, or on the nearest Monday to it. It cannot escape notice that the European Labour Day comes in Spring, at a time of planting and promise, whereas the US Labor Day comes in the Autumn, when the harvest is in. It highlights the difference between hope and achievement.

The difference between the two Labour days also illustrates the difference between Socialism and Capitalism. Socialism is full of promise and aspiration, but does not achieve in practice the results it aspires to. Most Socialist countries have been racked by shortages and shoddy goods, some even by famines. Inflation has abounded in many. Never do its Springtime plants deliver their hoped-for harvest.

Capitalism has delivered the goods. Its harvest is in, and has lifted more people out of subsistence and starvation than anything else people have ever done. Its wealth has eliminated malnutrition for most, extended life expectancy, reduced child mortality and deaths in childbirth.

Socialism is Spring; Capitalism is Autumn. By all means enjoy the Springtime hopes of better weather and a better world. But more realistically, enjoy the Autumn achievements of human success, and reflect on what it has taken to bring it to pass. Happy Labor Day.

Expropriating the rich

There are many out there who insist that we really must, just must, expropriate the rich. We’ve even seen one buffoon state baldly “We must tax the rich because they are rich”. It’s also noted, a la M. Piketty, that the rich have been expropriated. Unfortunately, he gets the mechanism entirely wrong.

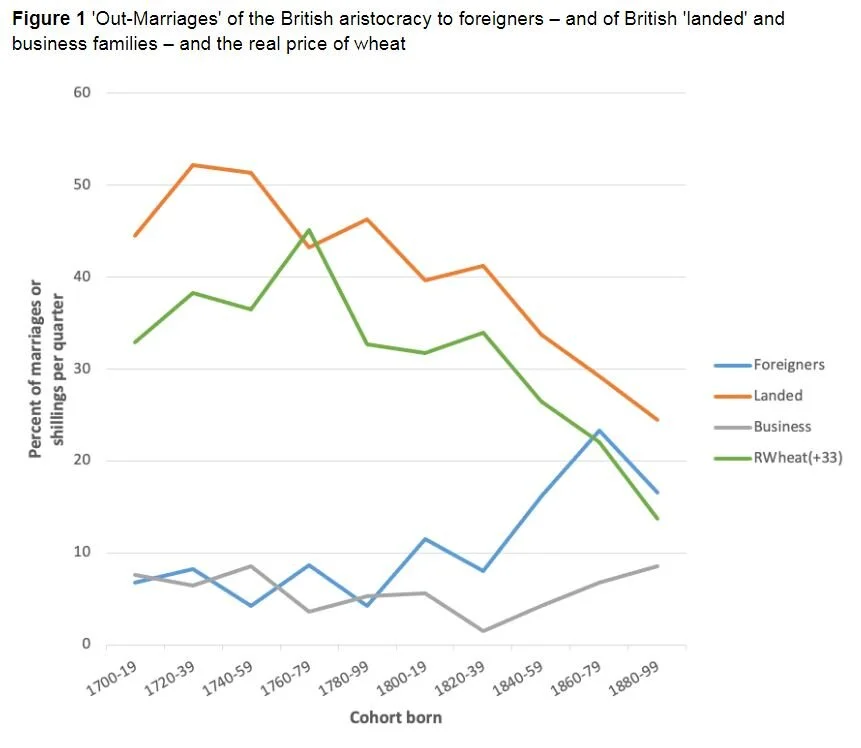

The premise of my recent paper (Taylor 2021) is that the rapid decline in British agricultural prices in the last quarter of the 19th century, which shrank not only the income of aristocratic landed estates but also the income of ‘commoner’ (i.e. non-aristocratic) families who owned land, led to a significant proportion of male aristocrats marrying American heiresses with rich dowries as substitutes for the traditional source – namely, brides from British families with landed estates but no titles.

British agricultural prices began their drop in the mid-1870s for several reasons, from the development of US railroads and prairies to the advent of steamships, all of which led to the UK market being flooded with cheap prairie wheat.

Agricultural land prices declined precipitately as a result of those changes. One marker of how much they did is that by the 1920s the income from an agricultural estate would not even maintain the buildings which the prices of a century before had been able to build.

But by the timing of this we can see that it wasn’t wars, taxation or government action - with one exception - that led to this expropriation of the landed classes. M. Piketty is wrong in his analysis. It was that technological change, the flood first of produce from the US and then, in the 1890s, from the Ukraine, that did. The government action was the revocation of the Corn Laws in 1846 which meant government got out of the way and allowed the technological change to so alter the wealth distribution. Those conservatives opposing the change were in fact right, the common man gaining cheaper bread would change their fortunes.

This is something that has a lesson for today’s social justice warriors. Technological change is what promotes social mobility by altering the value of assets and income streams. In a time of technological change one cannot remain at the top of the societal pile by simply sitting, lumpen, on the useful assets of the previous economic model. In our current day we could note that it is the geeks inheriting the earth but their time will pass too, as did that of merely owning land.

That lesson being that those who desire more of that social mobility need to support the system which best promotes technological change - that is, of course, free market capitalism. Those those arguing for social mobility need to be arguing for more free market capitalism and a lot less protection of the incomes and assets of the current generation of top dogs.

Oh, and that lesson of how to actually deal with those entrenched asset holdings. The way to expropriate the rich is to compete it out of them, not confiscate it.

Be careful of conflating pay and living conditions

While making a case - which we’re not commenting upon right here and right now - against raising national insurance this point is made:

Nor have most people enjoyed a long period of steadily improving living standards, of the kind that might make them more inclined to be generous. Real pay, immediately prior to the pandemic, was still below the peak it reached under the last Labour government. Conservative-led governments delivered a lost decade for earnings, especially for the young.

The is both a logical and empirical error. Real pay and living standards are not the same thing. We may indeed say that they should be, for what we hope to measure and discuss as real pay is those living standards of those who gain that pay. But that’s not how it actually works out.

Real pay is derived from adjusting nominal pay by the inflation rate. This rather leaves out much of the effect of technological advance.

Assume, for the moment, that the peak in nominal, and by this calculation real, pay was in 2007, before the Grand Crash. That also the year of introduction of the iPhone, the first mass market smartphone. Even if nominal pay, or real as adjusted by the general inflation rate, has remained static does anyone really believe that a world with more smartphones (in the UK at least) than people now as opposed to none then has had static living standards? Or broadband, which has risen in average speed from some 2 Mbits to 90 or so. Streaming was hardly even a thing back then, nor was mobile internet. Facebook only went to general availability in 2006. So too did Twitter launch that year - for all that second may or may not be an addition to living standards.

The idea that living standards have been static since 2007 is absurd.

As to why, inflation calculations deal badly with new tech. Those two social media sites, being free, aren’t included at all nor are they in GDP. But inflation is calculated from the consumer basket - things that lots of people do in proportion. Which, by definition, doesn’t include things that no one does, nor what few people do as a new technology starts out. Only when many people are doing it does it enter the basket and become part of inflation. But that’s also after the first mass reduction in price which accompanies the change from rich man’s toy to mass acceptance which is the path of all new techs.

It’s simply innate to inflation calculations that they don’t deal well with new tech.

One set of estimates- probably the best we’ve got - says that WhatsApp is worth $600 a month to users, Facebook $50 and Search engines and free email (so, Google) $18,000 a year.

Or, as we might put it, the reason that real pay isn’t reflecting the rise in living standards these past two decades is because we don’t measure the rise in real pay properly. After all, it is supposed to be how much do we get for an hour of our labour? If that’s rising then so is real pay.

The next sector for international trade - cannabis

The Guardian tells us of how aged grandmothers, trying to bring up their AIDs orphaned grandchildren, illegally grow marijuana in the mountains of Swaziland:

In Nhlangano, in the south of Eswatini (formerly Swaziland), the illegal farming of the mountainous kingdom’s famous “Swazi gold” is a risk many grandmothers are ready to take.

In what is known locally as the “gardens of Eden”, a generation of grandparents are growing cannabis, many of them sole carers for some of the many children orphaned by the HIV/Aids epidemic that gripped southern Africa.

The plots of marijuana are tucked away in forests in the mountains. Around one tiny village alone, the Guardian counted 17 fields of cannabis plants.

Noncedo Manguya is the breadwinner for her family of five grandchildren and two other children from her extended family, who were left in her care after the death of their parents. Manguya, 59, struggled to find a job or start a business and makes money by illegally growing marijuana, or dagga, that she sells on to dealers in South Africa.

This sounds like the sort of thing we ought to encourage. Not, we hasten to add, that we encourage there to be more orphans, or impoverished grandmothers who must break the law to feed them. Rather, the international trade which will make all of us better off.

We in the rich countries are finally - much too slowly but finally - getting sensible about cannabis. Both in the sense that we do own our own bodies and thus do, righteously, decide what goes into them and also in the more practical sense that prohibition simply doesn’t work. So, in fits and starts, medical, recreational, decriminalisation, legalisation, we’re changing the rules. But the one part that isn’t being changed is to allow international trade. Or at least that sensible policy is lagging domestic.

This is straight Ricardo, comparative advantage, even the laws of one price and all that. For as the UN reports (admittedly, old figures, 2006, 2008 and the like) marijuana herb is $40 in Swaziland, in not quite next country over, Malawi, it’s $10. In the UK from $5 to $15.

Except those Southern Africa prices are per kilogramme, the UK ones per gramme. A thousandfold price difference is the sort of thing international trade is made of. Legalising that would mean higher prices to the farmers, lower to consumers and human utility - not to mention pleasure - increases at both ends. And the region does already provide a significant portion of the global tobacco supply so the at least beginnings of the necessary infrastructure are there. There are also the beginnings of attempts to make this happen too.

We should do more to make this happen properly. Throw ourselves open to international trade here, to our own benefit and that of the producers.

The biggest opponents will be those who already try to grow cannabis in our own less amenable climate. Plus, there seems to be some infestation of the cannabis cheering classes with an anti-trade, anti-big business worldview. We do expect that thousandfold price difference to win out over such opposition, even if only eventually. And lets face it, we’re used to domestic producers being against international trade, aren’t we?

But let’s start right now. Whatever level cannabis consumption is at in any particular jurisdiction make the international production and trade in it subject to exactly the same rules as any domestic. Prices will tumble at our end and grandmothers will feed their orphans better at the other.

Sounds like a plan.

The purest nonsense about American wealth inequality

The latest bemoaning of wealth inequality in the US:

The shocking racial wealth gap between families, and its impact on Black and Hispanic kids, is revealed in groundbreaking new research by scholars on US inequality. It shows that the basic wealth levels of families from different racial and ethnic backgrounds have diverged to such a stark degree in the past three decades that the future prospects of children from lower-wealth groups are likely to be grossly compromised.

In 2019, the median wealth level for a white family with children in the US was $63,838. The same statistic for a Black family with children was $808.

It’s the purest nonsense. The full papers are here. The crucial error is here.

National levels of income inequality have long been shown to be shaped by labor-market institutions and welfare states

In their measurements of wealth inequality they, determinedly and in common with other wealth studies, refuse to incorporate the effects of welfare states. Just to remind, yes, the United States does have one of those even if it’s a little different.

As an example, and not one that specifically applies to families with children, the capital value of Social Security as a retirement income can be put in the $300,000 to $600,000 range - depends upon full or minimal benefits, expected lifespan, assumed discount rates and all that. Being naughty and extreme with those numbers, a racial wealth gap of $363,838 to $300,808 looks a great deal less alarming.

Now add in Medicare (of more interest to those in retirement of course), Medicaid, free schooling, unemployment insurance, the EITC and Section 8 (both of a great deal more interest to families with children, as with the schooling) the child tax credit and on and on up to and including free cellphones.

Their measurement of wealth inequality is before all of those things done which reduce wealth inequality. As a decision making tool it is therefore valueless for what is desired before deciding whether to do more, less or nothing is what is the situation after what is already done?

Further, don’t forget one rather important point. If everything government does which reduces wealth inequality is to be disregarded then it’s not a problem that can be solved by government, is it? For we’ll have to disregard the effects upon wealth inequality of what government does.

We do so enjoy the New Economics

The world has entirely changed, so we’re told in The Guardian:

Their problem is that many of the issues exacerbated by the pandemic, such as wage stagnation, precarious work and rising inequality are not bugs in an otherwise well-functioning system, but inevitable outcomes of the way that western economies are now organised. So a business-as-usual approach simply won’t work. Much more fundamental change is needed.

Global neoliberalism hasn’t produced much growth so we must have a different system that produces growth. Well, OK, not much growth except for the greatest reduction in absolute poverty in the history of our species.

Still we must have change:

Unlike his predecessors, Biden is pursuing large-scale public spending and taking advantage of ultra-low interest rates to borrow for infrastructure investment. His stimulus plans target the climate crisis while creating green jobs and expanding health, education and childcare – the “social infrastructure” that is essential to the economy but has often been ignored by mainstream economists.

That’s more generally called current spending rather than investment in infrastructure. But, change!

This was followed by long years of austerity and slow growth, stagnating wages, stalling productivity and extreme inequality.

We must have that more growth!

As long as low interest rates keep the cost of borrowing affordable, and borrowing is used to fund investment (which raises future national income and therefore brings in more taxes), the ratio of debt to GDP will ultimately fall.

Not just will the growth pay for all these lovely things, we need the growth in order to pay for the lovelies.

We’re really pretty sure this has all been tried before. Sweden quite famously retreated from it a few decades back. But still, the true glory of the New Economics argument is here:

Above all, many are starting to realise that economic policy needs to end its fixation with growth. Growth was never the only aim, but economists long assumed that it would solve most other problems. It’s now clear this was never the case. New ideas for “post-growth” economics are emerging, which focus on environmental sustainability, reducing inequalities, improving individual and social wellbeing and ensuring the economic system is more resilient to shocks.

As well as complaining that global neoliberalism doesn’t produce growth, therefore we need more government to have more growth and, also, we must invest to get the more growth to pay for the investment, we don’t need and shouldn’t have growth anyway.

Believing entirely contradictory things is oft taken as a sign of a certain mental fragility and we used to have comfy places for people to recover from such. That system was abandoned but we were unaware that it was replaced by positions in economics departments:

Michael Jacobs is professor of political economy at the University of Sheffield, and managing editor of NewEconomyBrief.net

Ah, that’s right, political economy isn’t economics is it? Nor, apparently, is it constrained by basic logic.