The Laffer Curve applies to the poor as well as the rich

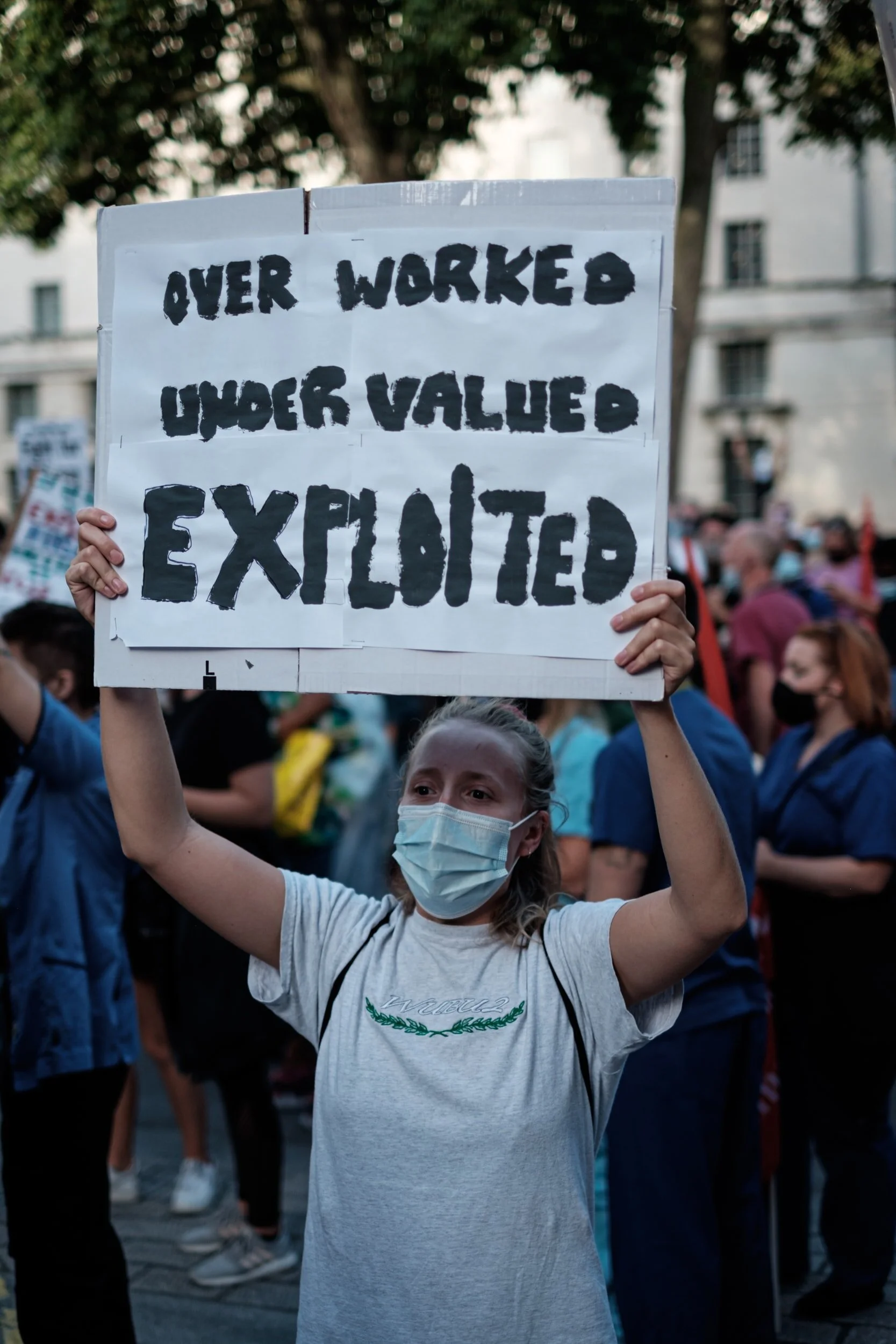

The point being made here is that at some rate of marginal taxation folks don’t bother going to work:

Buried in a government-commissioned report published this year is a clue to the reason some employers are finding it so difficult to attract British workers to lower-paid jobs.

Universal Credit (UC), the author said, “can act as a disincentive” to those in the jobs market because working age people “do not believe there is sufficient reward” if they try to stand on their own two feet.

It is the latest version of the so-called “benefits trap”, in which potential employees choose to stay at home, living off generous welfare payments, because working for a living would make them only marginally better off.

It is also part of the reason for the Government’s current spat with business leaders, who see cheap foreign immigrants as the answer to all labour shortages, rather than paying higher wages to attract British workers, as Boris Johnson wants them to do.

While UC ensured that people were always better off if they work, the intricacies of the system mean that many workers are only £3.29 better off for every hour they work if they decide to enter the labour market.

Assuming an average wage of £10 that’s a marginal tax rate of 67%. £10 sounds about right for people entering work really.

This links in with the Laffer Curve of course, it is that substitution effect - effectively, it’s not worth working for that, I’m off fishing - which causes the peak tax collection as a result of the tax rate.

This telling us something important and generally not thought about much. That peak of the Laffer Curve applies to the poor going to work as well as the rich. The answer to our becoming a richer nation is therefore to lower that tax rate. Or, in the intersection of benefits and tax, the combined tax and taper rate.

This is why 15 years ago we started to say that the personal allowance should be whatever the minimum wage is - full year, full time that is. We even managed to get there except a decade late. The personal allowance today is what that full year, full time, minimum wage was in 2010 - £12,500 a year - when the point was first accepted as being valid.

Time to make that point again. The very reason there is a minimum wage, not that we agree with there being one, is that this is the minimum that someone should righteously be paid for their labour. That means that government get to keep their fingers out of that wallet just as much as anyone else. If that means the personal allowance must be raised to £18,000 a year or whatever Boris is about to announce the minimum wage is to be then so be it.

We’ll just have to have a little less government in order to pay for it, won’t we?

When the lights go out, blame the Treasury

In zero carbon 2050, the UK energy requirements will be almost entirely supplied by three categories of electricity generation: renewables, nuclear and “counter-renewables”, by which I mean power plants that can be switched on, or otherwise varied, at short notice when the wind and sun are not delivering. In 2020, wind produced less than 4GW, i.e. one sixth of capacity, on a few occasions across 207 days. Demand averages around 30GW but is often 40GW in winter and can peak at 49GW or more. Nuclear should be, by 2050, the main steady-state producer, i.e. responsible for the “baseload”, i.e. the minimum non-varying requirement, although gas with carbon capture and storage (CCS) is a contender for that role. The main counter-renewable will remain gas + CCS, Bio-mass can be regarded similarly. Imports, currently 10.7% of the electricity market, will be a key element. Hydro is too small to be included in these notes and hydrogen is not a source but a storage mechanism which itself requires more electricity for its production than it replaces. It is, however, an ideal use for excess production from renewables.

The UK imports 35% of its total energy needs. It is difficult to determine electricity’s share of the total UK energy market as the figures for fossil fuels include usage for electricity generation which needs to be subtracted. In the absence of a better number, we should assume that electricity is 50% of the total.

“Nuclear installed capacity peaked at 12.7GW in 1995, with the opening of Sizewell B – the last nuclear reactor to be opened in the UK. In this year, nuclear accounted for more than a quarter of total electricity supply.” By 2018, that had shrunk to 18.7%. Generation peaked in 1995 at 12GW, but no current plants will be operational by 2035. Those under construction and planned (in 2018) should be producing 9GW. That estimate is not changed by the just announced Wylfa, Anglesey, as it replaces Bradwell which is no longer planned (but might be reinstated!). Using the 50% assumption, nuclear supplies about 10% of the current energy requirement.

Looking forward to 2050, when virtually all energy will be electricity and the population, and perhaps therefore total energy need, has grown by 15%, the current 9GW planned nuclear production would only supply 8.7%. A number of commentators have claimed the UK will need another 40GW of baseload capacity by 2050. If that should all be nuclear it means more than quadrupling the UK’s nuclear electricity generation capacity by then. Even with the Treasury’s new-found enthusiasm for nuclear power, that seems a little unlikely. The projected purchase of 16 Rolls Royce Small Modular Reactors would only be the equivalent of two more Hinkley Points, i.e. 4.6GW. But that is still speculative. The first working model is hoped to be operational in the 2030s. Meanwhile, other small nuclear reactors, e.g. those using molten salt and operational in the 2020s, are being ignored by the UK Government.

As things stand, the gap would have to be filled by gas + CCS. The risk is that, whilst we do have the technology for small and large nuclear, CCS is still at the developmental stage. The Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) published comparative costs for the main alternative sources in August 2020. They ranged from £44 per kilowatt hour to £85 for gas + CCS. Nuclear was omitted on the ground that it was commercially sensitive. The report did, however, say “The Government’s ambition is for the nuclear sector to deliver a 30 per cent reduction in the cost of new build nuclear projects by 2030, as set out in the Nuclear Sector Deal published in 2018.” Of course, ambition and results do not always match.

In the previous (2016) report, Chart 6 shows that nuclear is 50% more expensive than solar or onshore wind, due to its high commissioning costs, but cheaper than the alternatives, even with these costs. Thanks to its negligible fuel costs (high for gas) it is far cheaper than any alternative candidate for the role of baseload supplier.

Four things are clear at this point: BEIS is so besotted with renewables and hydrogen that planning for a secure, least-cost baseload is woeful, if it exists at all. Secondly, HM Treasury’s 20 year refusal to even consider adequate nuclear provision has got us into this mess. And they are not alone. The National Grid update on trends dated March 2021 does not mention “nuclear” at all. Thirdly, imports and consumer prices are likely to go through the roof. Nuclear is by far the strongest candidate for the provision of the baseload but unless BEIS accelerates nuclear development very rapidly, either the lights will go out or the UK will be stuck with gas + CCS with massive costs to the consumer. The current indifference to 4th generation small reactors is perverse.

A little history is a useful thing

Apparently it’s something or other that there are so few black figures (we use that description because that is what the source is using) commemorated by those blue plaques stating that someone famous lived here.

Blue plaques commemorating notable black figures still make up just 2.1% of the individuals honoured across London, according to a Guardian analysis.

The scheme, run by English Heritage, was started in 1866 with the purpose of commemorating figures who have lived, worked or stayed in buildings across the capital.

More than 1,160 notable people are name-checked on the scheme’s 978 plaques.

A little history would be useful here. The enrichment through diversity of Britain - and it is indeed enrichment - is a very recent phenomenon. According to the usual Census figures about 1.5% of the population is currently of Afro Caribbean background, another 1.5% of Black African (using the Census definitions and names) for a total of 3%.

In 1939 the total black population of Britain was about 10,000 souls, perhaps a little under - 0.02%. The arrival of the still segregated American army in those war years boosted this by some 1,500%, near all of whom left again in 1945. Then came Windrush and so on but the significant growth is in recent decades.

So, what percentage would we expect in a scheme that has been running since 1866? Further, one where consideration for a plaque cannot be done until the individual has already been dead 20 years?

We’re not arguing that the past was a perfection of equal treatment and we’d not even strongly insist that today is. But a complaint that the capital has too few commemorations of people who, to a great extent, were not actually there doesn’t strike us as anything other than evidence of an ignorance about that past.

But then, you know, Guardian investigations and all that.

The thing is, Chris Loder MP does actually have a point

Or perhaps, it’s possible to divine a useful and important point in what Loder is saying even if it’s not quite the one he thinks he’s making:

Mr Loder said: “It is in our mid and long-term interest that these logistics chains do break.

“It will mean the farmer down the street will be able to sell their milk in the village shop like they did decades ago. It is because these commercial predators – the supermarkets – have wiped that out and I’d like to see that come back.”

Any rational examination of what a supermarket is will conclude that it is, in fact, that logistics chain. The shop itself is just the box at the end. The economic entity is that chain that fills it - the logistics.

We insist that said logistics is one of the grand achievements of the modern age as well. We’d not want to see them break any more than we’d like to be in the age before penicillin.

However, we do insist that we believe in markets, markets untrammelled by unnecessary interventions. Which means that we’re entirely happy with, even insist upon, competition among models as well as specific participants within the one model. So, why is it that the local farmer cannot sell in the village shop?

Actually, it’s because we have specific regulations against it. At least, it’s illegal to sell raw milk other than directly, selling it through a shop is verboeten. In Scotland, even direct sale is illegal. This means that the farmer must pasteurise the milk at the farm. Or, must sell direct at the farm gate, deliver directly to households - or must sell to a wholesale operation that does the pasteurisation.

At which stage there is actually a point in what Loder says. We don’t want to break the supermarket logistics chains, not in the slightest. But we’d be entirely on side with reducing regulation, freeing up the supply side of the economy, so that alternatives can compete on a level footing. For the benefits of competition come not just from battles between different people being more or less efficient at doing the same thing but also - and more importantly too - from different methods of doing different things.

Power Games

“UK energy policy since the 2008 Energy Act has largely been built around reducing carbon dioxide emissions rather than security of supply or cost”. It may be too much to expect of recent governments but they should have grasped that, removing fossil fuel dependency would require more electricity in total and nuclear power would be better value than the alternative, namely gas plus carbon capture and storage (CCS), for providing the steady “baseload” generation to complement renewables.

The sun does not always shine and the wind does not always blow. Indeed, the only thing that is certain to blow with the wind is government policy. At the beginning of 2021, the proposed nuclear power station at Wylfa Anglesey was cancelled. The government blamed the change of heart for that, and terminating Oldbury, on “the impact of the falling prices of renewable energy in recent years”. The vital need for the baseload to provide continuity appears to have escaped the minister. In September, in response to surging gas prices, Wylfa was back on the table, albeit with a new partner.

A Treasury swing-around, from anti- to pro-nuclear, appears to have taken place in the last week or so. It seems to have been prompted by the immediate gas price crisis. Watching these developments reminds one of the “....Goes Wrong” plays. We know what is going to happen but it’s our money and not really very funny. In 1992, the Treasury decided it would cunningly meet the requirement for more hospitals and other capital projects, which it claimed not to be able to afford, with public private partnerships: the Private Finance Initiative (PFI) was born. It was fundamentally a good idea but the civil servants, having little idea of how to manage such projects, consulted clever bankers in the City about how to ensure clever bankers did not excessively profit. Of course, it all went wrong and the clever bankers got excessively rich. By the time PFI was ended in 2018, PFI deals had financed £12 billion of English hospital building at a cost to the NHS, namely the taxpayer, of £79 billion in repayments. Fast forward only one year and history repeats itself. HM Treasury has been blocking new nuclear plants for 20 years on the grounds that they cannot afford them. Energy has been privatised so the private sector should pay for new energy plants. The trouble with that is large nuclear power stations can cost £23 billion a pop and take 20 years to get approvals and build. No private companies can afford that. So the Treasury has come up with the Regulated Asset Base (RAB) model for nuclear as their solution.

After 20 years, one might expect the flood gates to be opened but not so: “the government will aim to bring at least one large-scale nuclear project to the point of final investment decision (FID) by the end of this parliament [i.e. in three years], subject to clear value for money and all relevant approvals.” If nuclear is to provide the baseload for a zero carbon 2050 and bearing in mind their long lead times, we probably need not one but 10 new plants (or the equivalent in smaller reactors) and in a hurry.

“On 22 July 2019 the Government launched a consultation on a RAB model for new nuclear projects that would have the following features ……

a) Government protection for investors and consumers against specific remote, low probability but high impact risk events, through a Government Support Package (GSP);

b) A fair sharing of costs and risks between consumers and investors, set out in an Economic Regulatory Regime (ERR);

c) An economic regulator (the ‘Regulator’) to operate the ERR; and

d) A route for funding to be raised from energy suppliers to support new nuclear projects, with the amount set through the ERR, during both the construction and operational phases (the ‘Revenue Stream’).”

Once again, the Treasury is trying to solve a problem it has itself created. Where does it say, in Holy Writ, that nuclear power stations can only be financed by the private sector? If that logic applied to other infrastructure, we would never have embarked on HS2 and we would all have been better off. However one dresses up major capital expenditures, the government can finance them at less cost because it borrows at lower interest rates.

The GSP is the Treasury’s promise to keep prices, i.e. total costs, down but, as the respondents to the consultation pointed out, the Treasury has not explained how the GSP will work. Either the government is in charge of the project from day one, and therefore is in at least nominal control of costs and timings, or it is not. The most likely reason for the GSP not being explained is that it is a fudge.

According to the Government’s consultation response, “17. For the ERR, we proposed a regime whereby the regulator granted a licence to a project company, allowing it to charge an ‘Allowed Revenue’ in return for construction and operation of the asset. The Allowed Revenue amount would be determined by the Regulator. Our initial analysis indicated that it would likely be more appropriate for the regulatory regime to be set ex-ante.” The respondents, being likely investors, supported the ex-ante approach, unsurprisingly as that would be more likely to generate higher returns for them. The Hinkley Point “strike price” was set ex-ante: “the deal guarantees that [the equity owners] NNBG will receive £92.50 (2012 prices), linked to inflation, for each megawatt hour (MWh) of Hinkley Point C’s electricity for 35 years [from when it becomes operational], with electricity bill payers paying top-ups if the market price is lower.” With inflation since 2012 being low, the £92.50 would have been £112 in 2020, i.e. well above the average actual UK wholesale average price of £70.59 per MWh.

The “Revenue Stream” is the whizzy idea that the project company is given all the money it needs to plan and construct the plant before it becomes operational and starts to receive income from selling electricity to the National Grid. The traditional commercial concept of using revenue to make a return on the original investment goes out of the window because the Revenue Stream will have taken care of the investment. As the running costs of nuclear power plants are very low, operational revenue, namely £92.50 + inflation in the case of Hinkley Point, will be almost all profit. I have asked BEIS what the strike price is expected to be for Wylfa but answer came there none. In the case of Sizewell C, where the US is pressing for the removal of Chinese investment, “EDF has been lobbying intensively for a RAB mechanism, arguing that it could slash the ‘strike price’ – the guaranteed price for Sizewell’s electricity – to between £30 and £60 per megawatt hour.” The paragraph above explains why they can well afford to do so. If the capital costs have all been covered by the Revenue Stream, there should be no need for any strike price. The wholesale price of the day should be quite enough.

But quite apart from anything else, why should the consumer have to pay for the construction of nuclear plants before they receive any electricity from them? Yet that is what is proposed: “65. If a version of the [RAB] model described above were to be used, a revenue stream would need an intermediary body to charge and collect payment from suppliers [who would want it from consumers], and to pass this onto the project company. Both suppliers and the project company would need to have confidence that the organisation which took on this function had the capability to do so effectively.”

It gets worse. Why have one new bureaucracy when one can have two? In addition to the “intermediary body” above, the Office for Nuclear Regulation (ONR) and Ofgem, the government proposes an ERR Regulator who “should have responsibility for protecting the interests of consumers, whilst having regard to the ability of the project company to finance the project i.e. construction and operation of the plant” (para 58). Its main role would be to liaise with all the other regulators: “The intention would be to draw on existing experience of cooperation between economic, safety and environmental regulators in other regulated businesses, whilst also taking account of any considerations specific to the nuclear sector. Each regulator would retain its complete statutory independence.” There can be little doubt that the interference from all these regulators would delay, and add to the costs of, new nuclear plants. To ERR, after all, is only human.

Reviewing the rest of these RAB proposals would take many more pages and try the reader’s patience. The simple truth is that the Treasury is making a mountain out of a molehill, and a very expensive mountain at that. Unless RAB is rejected consumer prices will be hugely inflated, the necessary nuclear projects delayed, and electricity security threatened.

Here is all that is needed:

Government should decide what new nuclear plants are needed and get them built on time and on budget. As civil servants are not known for high level commercial skills or successfully managing major projects, management should be outsourced with incentives to minimise costs and construction time. Where management can identify unnecessary delays caused by any part of government, the latter should be financially penalised.

Regulation should be left with Ofgem, which itself needs reform. The “intermediary body” and the ERR Regulator proposals should be dropped and the ONR should be closed. It duplicates the safety investigations of the US and Canadian authorities who have agreed cooperation aimed at mutual recognition of nuclear approvals. The UK could join in that.

Once operational, the nuclear plants should be privatised.

The Treasury is good at being the Treasury and playing political power games but not at providing the country with the electrical power it needs at least cost. It stepped away from the Bank of England and it should step away from this.

What's wrong with the labour market?

There’s a distinct sound of head scratching going on out there. We’ve a record number of job vacancies, lots of unemployed people and yet no one seems to be getting hired. What’s going on?

Britain’s employers might be struggling to fill a record 1 million job vacancies amid the worst labour shortages in a generation – with a lack of lorry drivers, hospitality staff and other workers vital for the economic reopening. But for millions like Cousin, navigating the jobs market remains tough.

With the end of furlough last week, hundreds of thousands of workers are likely to be on a similar journey. Many are expected to drift into early retirement or put off their job search until their sectors recover.

Despite a gradual fall in recent months as firms scramble to recruit, official figures show unemployment is still almost 200,000 higher than before Covid, standing at more than 1.5 million.

The answer is in the Nobel winning work of Chris Pissarides and colleagues - frictional unemployment. It takes time to run through the jobs on offer and decide which one seems suitable. It takes time to run through the applicants and ponder which seems the best fit. Therefore there will always be some part of the workforce going through that run through and ponder process.

We would expect that the greater specialisation of the modern economy will increase the time it takes. We’d also expect that online job searches and advertising will reduce it. The growth of the human resources bureaucracy in most organisations might well increase it again. We end up with the balance we have.

The warning for us is to ponder a further point. How much worse would it get with more bureaucracy? If we had all those insistences about checking social class of parents (an actual thing that people are trying to insist upon), race, gender, and so on and on? Things would be worse.

The lesson being that there are costs to absolutely everything as well as benefits to many. Any decision making process has to weigh both.

Folks, they're making the New Soviet Man mistake again

The arrival of New Soviet Man was at first ecstatically predicted, then grimly awaited and finally the non-arrival mourned. For those who devised the socialist system were fully aware that human beings did not in fact act in the ways that would make such a system work. But that’s fine, build the system anyway and await that arrival of the new type of human who would make the wheels turn and the clocks tick.

This is the New Soviet Man mistake. To insist that folks will be, or are, how they need to be for your idea, your system, the plan, to work. Rather than observing how they are and then devising ways to deal with that nature:

The British like to think that they have a uniquely profound understanding of class. In truth, it’s the opposite. The arcane rules of the country’s class system mean we have a deranged understanding of our divisions, one that is informed not by whether someone owns financial assets or capital or employs people, but by their accent, hobbies and choice of supermarket.

That’s exactly the mistake being made there. Man is a purely economic being, we should view relationships between men in those purely economic terms. Thus class must be defined solely in those purely economic terms, capitalist, bourgeois, prole and the one rarely mentioned these days, lumpen. That this is necessary to make Marxism work as a method of understanding society and that we’re using Soviet to describe it is just a coincidence - any manner of describing humans as other than they are is that new man problem.

For we in Britain do not define class in that manner. It is about accent, education, interests, even, as George Mikes pointed out, shaving upon Sundays. The only ones who didn’t in his day were the toffs and the lumpen - everyone else did. Similarly, it’s long been a standing joke that the worst dressed person in the room is the toffest - to the point that a snide about Michael Heseltine was his mistake in getting his hand made suits to actually fit him.

Perhaps it’s even true that we ought to regard class purely through that lens of economic relationships. But we don’t and that’s all there is to it. Plans devised for the British have to deal with us as we are, not as we should be to fit the plan. Anything else is to condemn to that wait for the New Man who isn’t going to turn up.

If only these people could manage to make up their minds

Apparently it is just terrible that large American companies - including much of Big Tech - is funding lobbying and PR on the subject of the law and climate change:

Some of America’s most prominent companies, including Apple, Amazon, Microsoft and Disney, are backing business groups that are fighting landmark climate legislation, despite their own promises to combat the climate crisis, a new analysis has found.

A clutch of corporate lobby groups and organizations have mobilized to oppose the proposed $3.5tn budget bill put forward by Democrats, which contains unprecedented measures to drive down planet-heating gases. The reconciliation bill has been called the “the most significant climate action in our country’s history” by Chuck Schumer, the Democratic leader in the US Senate.

Not that we’d believe Chuck Schumer if he said the sky was blue but still - the insistence is that it’s bad the companies are lobbying upon climate matters.

Yet it was only last week that the same newspaper reported that it’s a terrible shame that large companies spend so little lobbying upon climate change:

The world’s biggest tech companies are coming out with bold commitments to tackle their climate impact but when it comes to using their corporate muscle to advocate for stronger climate policies, their engagement is almost nonexistent, according to a new report.

Apple, Amazon, Alphabet (Google’s parent company), Facebook and Microsoft poured about $65m into lobbying in 2020, but an average of only 6% of their lobbying activity between July 2020 and June 2021 was related to climate policy,

Perhaps a little work could be done on making up minds here. Is corporate lobbying a good thing or a bad one?

Ever such a slight problem with this renationalisation of the utilities idea

Knowing a little history is one of those things that could be useful here:

The privatisation of public services is a 40-year failed experiment that voters have had enough of. Recent polling shows that 74% of potential Labour voters now support a greater commitment to public ownership. Evidence suggests that Labour’s public ownership policies were always popular with the general public, and became even more so from 2017 to 2019. Brexit and the party leadership were the stated factors that stopped people from voting Labour. Even Conservative voters support public ownership of railways and water utilities. That’s because in general, people want to see profits reinvested into better services rather than leaking out to shareholders.

To use just the example of the water utilities:

The water industry in England has been transformed since privatisation 30 years ago. It’s easy to forget how bad things were, so it’s worth reminding ourselves.

After decades of underinvestment by successive governments water quality was poor, rivers were polluted, and our beaches were badly affected by sewage. Quite simply, the water industry was not high up the list of priorities for Ministers when its funding came out of the same pot as the money for schools, hospitals and police officers.

Now we agree, something called “Water UK” might not be the most entirely unbiased source. But that basic claim is true. Precisely because any profits from the water industry - and by logical extension, other publicly owned utilities - went into the general revenue pot to then be spent according to political priorities not a great deal went into reinvestment in better services.

Investment in the water companies - the water and sewage systems - rose substantially after privatisation.

We do agree that it’s theoretically possible that government deciding upon investment levels can or could lead to the optimal amount of said investment. We also insist upon pointing out that that’s not what actually happened.

Which does lead to an interesting question, doesn’t it? How can renationalisation be the solution to the problem that privatisation solved itself? How to increase the investment in the utility systems?

An interestingly difficult argument to make about mineral availability and the circular economy

We are told that there’s really no need to go deep sea mining because there’re plenty of minerals around without doing that:

Electrification of vehicle fleets is a “positive pathway” to reduce carbon emissions, says McCauley. But he accuses deep-sea mining companies of a “false narrative” that we must mine the ocean to meet renewable energy’s demand for metals.

We have an interesting example in the same newspaper on the same day. There’s vast amounts of lithium in the geothermal waters underneath the Salton Sea:

But as disastrous as the disappearing Salton Sea is, powerful people believe that a vast reserve of lithium locked beneath it and the surrounding area holds the key to flipping the region’s fortunes.

The Salton Sea thing is true by the way, just as there’s lithium underneath Cornwall, the Krusny Hory and many other places. For the same reason that we’d no go deep sea mining for that particular element, it’s soluble. We can, in fact, extract it from seawater itself even if that’s currently rather expensive -as might be that extraction from geothermal waters, something that remains to be found out.

But d’ye see the logical problem here? If it’s true that there are those vast resources meaning that we don’t have to go deep sea mining then what’s the argument that we must have a circular economy because of the lack of available resources? Why do we have to recycle everything if there’s plenty of it?

It’s difficult to argue both at the same time, there’s plenty but there isn’t. Still, no doubt some will still try to insist on both at the same time. Sadly, many of those some seem to be the people making policy.