Not quite getting the point about regulation

It’s not that this view of regulation is wrong, it’s that it’s incomplete:

The hi-tech startup with a new drug that, say, relieves Parkinson’s disease or a piece of kit that diminishes the toxicity of car exhausts will grow faster if the company can assure its buyers that its products have been tested and have passed the regulatory standard. They will grow even faster if they can assure European and American buyers they conform to European and American standards.

This is true as far as it goes. Assuming that there is a new piece of kit then being able to sell it into wider markets is of benefit.

But the basic insight of economics is that there are no solutions, there are only trade offs of varying levels of desirability. What’s being missed here is that regulation at the earlier stages of that development process will lead to less development of new kit.

From a project that has been floating around for some time - a new method of separating rare earths. Something that would be fairly useful in the present industrial environment. To test - using modern tech and knowledge - a supposition from the 1950s. No, don’t worry exactly what it is, but one of those things that in theory will work, has been shown to work on a lab bench and now needs to be tested in the tens of to hundreds of kilos at a time. So-called “pilot-plant” stage.

The cost of buying the kit to do the testing, running the test, about £250,000. The cost of gaining the relevant permissions to be allowed to run the test? About £250,000. Under certain interpretations of the REACH regulations it’s not possible to faff about in a lab, to that pilot-stage, to see what happens. Instead it is necessary to gain full environmental permissions for every experiment that is done.

This undoubtedly reduces the amount of interesting experimentation that is done on things that might work out, might not. For we’ve just doubled the cost of doing that experimentation.

Yes, regulation has a value. So does the absence of regulation. Any flat-out statement that regulation is worth it is wrong. As is any flat-out statement that regulation is not worth it. It depends upon which regulation, stating what, then a calculation of what is not happening as a result of the regulation. Yes, of course, less pollution has a value - but so also does experimentation into what can be done. It’s the balance - as with everything else in a world as complex as this one - which matters, not the insistence that “this” or “that” is good all on its lonesome.

That one of the examples used by Willy Hutton - for of course it is he - is a new pharmaceutical adds to the piquancy of the statement. For it not only costs some $2 billion to get a new drug to market these days it is also true that America’s FDA adamantly refuses to allow approval elsewhere, to other standards, to influence its decision. Each and every drug must be separately approved by they themselves. It’s one of the major proposals to make the world a better place that the Americans actually accept European - or UK, or Japanese etc - drug licensing rather than insisting upon their own system.

If only those who would rule our world actually understood our world.

Those darn supply curves

From the British point of view this is just another of those oddities we must observe. From the American it is more important than that:

Under the NHS’s Voluntary Scheme for Branded Medicines Pricing and Access (VPAS), pharmaceutical companies agree to help subsidise the cost of the health service’s drugs bill if it rises by more than 2pc. The rate of how much companies are charged ultimately depends on how big the NHS’s medicines’ bill is and how fast it rises.

If drug prices rise then the drug manufacturers must “compensate” the NHS for those price rises. Or, if prices rise then prices must not rise. This has logical effects:

The repercussions of a sharp spike in these levies are prompting some less well known manufacturers to pull out of supplying Britain altogether.

This is particularly the case for companies manufacturing so-called “generic” drugs – medicines no longer protected by patents and so made and sold for far less. Generic medicines account for four out of every five prescription medicines used by the NHS and four in every 10 of them fall under the VPAS scheme.

“These companies run on very thin margins, so when the costs increase, including VPAS, it does make some products loss making,” says the British Generic Manufacturers Association’s chief executive Mark Samuels.

“At that point, companies will really look at whether that can supply the NHS, because no business can sustain supply of products at a loss for very long.”

We’re deliberately reducing the prices suppliers can charge. This moves us along the supply curve to where we get shortages of drugs. Oh well, there’s that basic economics shouting at us again. Shrug.

The Americans though, it’s long been an insistence that the Feds should be able to bargain with the drug companies over drug pricing. The NHS is offered as the justification, see, they do it therefore so can we.

Well, yes, the NHS does do it and see? Just like economics 101 states, reduce the prices to be paid and move along that supply curve. This might not be something that you want to do therefore. You know, don’t copy one of the - many - things the NHS gets wrong?

ASH is just gasping at trivia here over single use vapes

We would, obviously, prefer defiant teenagers to vape their way into coolness rather than smoke. At which point ASH decides that this should be taxed out of existence, this lower damage method of teenage rebellion:

Add £4 to the price of every vape to put off children from buying them, campaigners have said.

Action on Smoking and Health (ASH) are calling for an excise tax on disposable vapes to stop children from being able to buy them for less than £5.

The charity said adding £4 to each single-use vape, which currently cost around £4.99, would make them significantly less affordable for children while still less expensive than tobacco.

One of the justifications put forward is:

It argued such a tax would also have an environmental benefit, with discarded single-use vapes equating to 10 tonnes of lithium being thrown away a year.

10 tonnes of lithium is worth perhaps £800,000 these days. In a more rational market - when the planned mines open - perhaps more like £80,000. That’s the input price, not the value as scrap.

10 tonnes of lithium is also a trivial amount. A world class mine might produce anything from 10,000 to 100,000 tonnes. So, the “waste” here is of the order of one thousandth to one ten thousandth of the output of the one mine.

Not that it is wasted of course - humans have had the use of that lithium so what is the waste?

The single use vape market appears to be worth some £750 million a year. At a fiver a piece that’s 150 million units. Oh, and when we run the numbers back the other way each vape contains half a penny’s worth of lithium. At today’s very high valuation that is.

Ten tonnes of lithium - despite the fact that this is becoming one of those little factoids that is doing the rounds - is trivia.

It’s also true that there is that Pigou Tax idea to think about. That there are externalities, not properly contained in market prices and a tax should be used to correct that. But that idea does insist that the tax should - must - be equal to the size of the problem. It’s not in fact true that this is an externality, that ha’penny of lithium is already included in the market price. But imagine it isn’t, the tax should be that half penny. £4 is overdoing it by only 800 times.

People are losing their minds here. This is like trying to judge the overall health of British sport by concentrating on the question of Sheffield Wednesday’s B Team left fullback. Something of interest to perhaps five people - the manager, the two potential fullbacks and their Mums.

As further proof of the insanity:

It comes as major supermarkets have pulled one of the most popular e-cigarettes from shelves after they were found to contain 50 per cent more nicotine than the legal limit.

Watermelon flavour Elf Bar 600s have been removed from shelves in Asda, Morrisons, Sainsbury’s and Tesco, with some chains stopping sale of the whole Elf Bar 600 range.

The move came after an investigation by the Daily Mail found between 3ml and 3.2ml of nicotine liquid in some e-cigarettes, while the legal limit is 2ml.

A spokesman for Elf Bar told the paper that some batches in the UK had been “inadvertently” overfilled.

Note that the claim isn’t that the vapes are too strong - it’s that they’re too good a deal. The naughty, naughty, people have been offering a 3 lb loaf of bread for only the price of a 2lb loaf. Terrors, eh?

There are indeed problems in this world but perhaps we should raise our sights and try to deal with them, not this sort of trivia.

So, who you reckon? Sam Reed or Jaden Brown, maybe Reece James for the A team then?

The problem with all macroeconomic policy

This claims that monetary policy comes with certain problems:

Monetary tightening is like pulling a brick across a rough table with a piece of elastic. Central banks tug and tug: nothing happens. They tug again: the brick leaps off the surface into their faces.

Or as Nobel economist Paul Kugman puts it, the task is like trying to operate complex machinery in a dark room wearing thick mittens. Lag times, blunt tools, and bad data all make it nigh impossible to execute a beautiful soft-landing.

That is all true - it’s also true of monetary loosening of course. Our recent 12% inflation rate is proof of that.

But the big bad truth about macroeconomic policy is that this also applies to fiscal policy. Which, given that there are only two macroeconomic toolsets, fiscal and monetary policy, leaves us with something of a problem concerning macroeconomic management.

Given the tools available macroeconomic management just isn’t going to be very good. Sure, if gross events occur - GDP drops 10%, inflation rises to 12% - then clearly a gross and inaccurate tool might be appropriate. But that Keynesian dream of managing, in detail, the temperature and speed of the economy centrally just doesn’t work. Not because we cannot make an intellectual case for it, but because the ability to do anything about it relies upon those gross and inaccurate tools.

The management of the economy therefore devolves down to those microeconomic matters that we both know more about and can indeed deal with. Incentives, the fine detail of market structures and so on.

This is not to say that we must have microeconomic foundations for our macroeconomic theories. Quite the opposite in fact - it’s to insist that our macroeconomic toolbox to be able to do anything about the macroeconomy isn’t very good. Therefore use must be sparing, in extremis only.

Get the structure of markets and incentives correct and she’ll be right, the economy as a whole being emergent from those.

This is, of course, very boring for those who would get all Fat Controllerish about the macroeconomy but it does have the startling merit of being both true and useful advice.

All hands on deck (chairs)

When the ship of state lacks direction, crowding the bridge with more Cabinet Officers and unfolding more deckchairs for the crew, will not avoid any icebergs.

Last week we had 30 around the Cabinet table - now there are 33. By statute there should be a maximum of “21 Cabinet Ministers excluding the Lord Chancellor.”(1) This changes the dynamic of those in the room from being decision-makers to being part of an audience.

Worse still, Commander Sunak is steering by hindsight. The policy of reducing the size of the civil service to pre-Brexit numbers has been scrapped. More deck chairs are being made available and the crew can work ashore if they like. When I grumbled about a senior Department of Health civil servant working from Gloucestershire, he told me he had just had approval to move his office to Cornwall…

A zero carbon 2050 implies that almost all energy will take the form of electricity. That rests on three legs: renewables, nuclear, and fossil fuels. Back in April, Boris Johnson recognised nuclear as the key to minimising fossil fuels emissions because renewables are unreliable. On more than 180 days in any year wind only produces 4GW (2% of electricity needs) at some stage of the day or night.

Remarkably, this fundamental issue is not even mentioned in the BEIS 2050 projections. (2) Johnson clocked it and created Great British Nuclear (GBN) to deliver it. Purser Jeremy Hunt, however, answering a question at an informal gathering of Tory MPs, replied that “Boris Johnson’s ambition to build one new plant every year for the next decade was unfeasible in the present environment."(3)

That means fossil fuels will remain the key leg. The current artificial pricing which is responsible for their record profits has little to do with Mr Putin and everything to with the government allowing them to base wholesale prices on alien products. The UK was buying very little gas from Russia: Norwegian pipelines were an issue and so was using the foreign gas market to set the prices for UK renewables. (4)

Another example of steering by hindsight is the re-merger of domestic and international trade departments. International trade used to be part of the domestic business department but its relationship with the Foreign Office did not work so UK Trade & Investment was formed in 2003 as a joint subsidiary of the two departments. That proved useless, partly because the three cultures did not mix, and in 2016 the Department for International Trade (DIT) became a stand-alone ministry in anticipation of Brexit. (5)

Now Commander Sunak is taking us back to where we started and history will repeat itself. All that said, dedicating one department solely to energy/net zero is a good idea but Lieutenant Shapps should be given his own lifeboat to row, free of constraint by the Treasury. Captain Hands, meanwhile, should be facing the titanic problem before him, and should clear his bridge of those looking back.

(2) www.gov.uk

(5) https://www.gov.uk/government/organisations/department-for-international-trade

As we were saying, Just Say No to HS2

Madsen Pirie describes our work here as to be those howling in the woods - shouting out those truly weird ideas and concepts which a decade later become the commonplaces of the political discussion. Which brings us to HS2:

The number of trains running on HS2 will be almost halved and services will travel more slowly in a proposed shake-up of the £72bn line as ministers scramble to save money.

Whitehall officials are considering reducing the number of trains from 18 to 10 an hour, insiders said.

Meanwhile, plans to run services at up to 360 km/h (224 mph) are in jeopardy as officials weigh whether to reduce maximum speeds.

Dropping the H is indeed one way to reduce costs. But in the newspaper report there is also this:

Lord Berkeley….He said: “Why do you need to get to London 30 minutes quicker when you have Wi-Fi and your laptop on the train?

“I suggest that ministers should look at options for radically cutting the costs of what is left of HS2.”

Ah, yes, as we pointed out just over a decade ago:

The economic case for HS 2 is dead

Unlike the trains themselves - or even the project - the truth is arriving just on time.

On-train wireless internet connectivity is growing fast in Europe - but even faster in the UK, which now has more than 2,000 Wi-Fi equipped carriages.

If people are productive while in a train then the benefit of getting them there faster disappears.

That's bad news for High Speed Rail though, as the justification for HS2 (the £17bn high-speed London/Birmingham connection) assumes all travellers are entirely unproductive during transit and thus the 30 minute reduction in travelling time benefits the economy.

We did get one part terribly wrong, that £17 billion was terribly naive. But the base point, once we have WiFi on trains then the economics entirely fall apart was and is true.

Of course, having been right isn’t enough, even if unlike Cassandra some now believe. It’s still necessary for someone to act on that rightness and cancel the thing.

This seems like a sensible idea

We criticise often enough so perhaps applauding something sensible should also be done:

Train tickets in Britain could be priced like airline seats under a demand-based system being trialled by the government as part of a wider rail shake-up.

The transport secretary, Mark Harper, announced on Tuesday evening that fares on some long-distance trains run by LNER on the East Coast line will fluctuate according to availability.

He said the state-run train company would also move towards scrapping return tickets across its network, as a test for whether the idea could eventually be rolled out across the wider railway. The trial follows a successful pilot of selling only single-leg tickets on some longer intercity journeys such as London-Edinburgh since 2020.

Airlines face the same basic problem as trains. Near all of the costs (near for airlines, all for trains) are the fixed costs of running the routes. The marginal cost of the extra passenger is near (or is) nothing. Thus the game is to maximise total revenue from the seats. That does mean variable pricing. This is then compounded by the manner in which an empty seat on a train/plane 10 minutes before departure has some value or other, that same seat 15 minutes later is worth nothing.

So, given that airlines have indeed found the solution to this problem over the past 30 to 40 years why not the same solution on trains? After all, solving an economic problem is indeed solving an economic problem. This also being an interesting proof that economics - at the level of microeconomics at least - is indeed a science. Generalisable principles extracted from observation and experiment, that’s pretty scientific.

Which does leave us with just the one question really. Why has it taken 30 to 40 years for a solution already known to be applied to trains? Possibly because whatever it is we’re calling the Department for Transport these days has retained control of ticketing methods?

Less lab space keeps us off the pace

The COVID-19 pandemic helped highlight our reliance on laboratories like never before.

The labs provided vital research into vaccinations, playing a vital role in overcoming the challenges presented by the pandemic. Even before that point, life science innovation has contributed to society in immeasurable ways. Including the development of antibiotics, the invention of gene editing techniques, and understanding the structure of DNA à la CRISPR.

In the UK, this innovation is largely concentrated in the Oxford-Cambridge arc, an area in which there is a distinct focus on academic research. Biotechnology companies buzz around this golden part of the South like bees to (profitable) honey, hoping to set up research laboratories across these cities due to their close proximity to highly intelligent science graduates who may go into research.

However, there is a colossal problem standing in the way of the continued development of vital research innovation. A problem so big that it could hinder the very safety of the British people come the next pandemic - a lack of lab space which handicaps the very research keeping us safe.

As shown on the graph below from the Financial Times, demand for lab space far exceeds available supply.

Sue Foxley, research director at Bidwells property consultants, explained in 2022 that,

“In June this year, Oxford had 18,000ft(sq) of lab space available for research-intensive SMEs, but the demand was vastly higher at 860,000ft(sq); Demand in Cambridge totalled nearly 1.2 million square feet, but the availability there was zero.”

With the UK unable to keep up with growing demand for lab spaces, we are at threat of losing potential innovation opportunities in the life sciences sector to cities such as Boston, where more lab space is available. We’re also at risk of a brain drain, forcing graduates from these research specialist universities to move further afield. Perhaps to another more attractive country.

You may hear people argue that we are fixing this problem by growing lab spaces in other parts of the UK, and indeed we have. In South Manchester for example, a £2.1 million deal has been passed, completing the sale of 10,000 sq ft of office space to convert into lab space. Similarly, in Edinburgh, 20,000 sq ft of space is currently being turned into lab space.

This is a step in the right direction but it doesn’t fix the problem in Oxford and Cambridge: the areas where clusters of innovative firms already exist. These innovation clusters, like the ones we see in Oxford and Cambridge, take years to develop. By building a series of lab spaces dispersed throughout the UK we would be missing out on agglomeration effects and thus losing out on the positive innovation opportunities that we see in Oxford and Cambridge.

How do we go about resolving this? We could repurpose existing spaces in Oxbridge into lab space. One way this could be done is by relaxing restrictions on Grade II buildings which take up a large percentage of all listed buildings in both Oxford and Cambridge (in Oxford and Cambridge there are 77 and 47 Grade II buildings respectively). While there is a reluctance to suggest this due to the ‘special interest’ these buildings have, due to the dysfunctional nature of the planning system, this seems like a necessary approach to ensuring an increase in lab space.

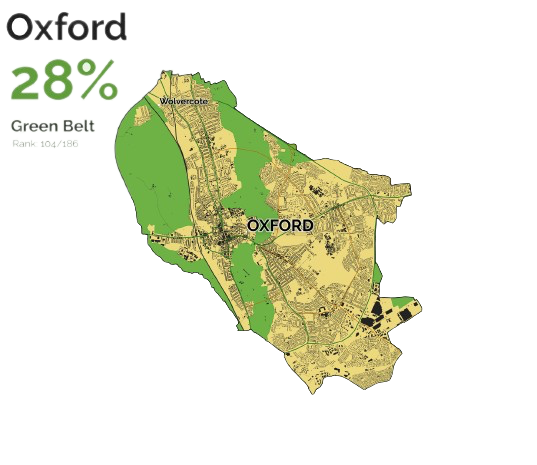

Another solution, as with the housing market in general, is to open up areas of the green belt for construction. Admittedly, Oxford and Cambridge are places with lower green belt areas in contrast to others in the UK, however there is still around a quarter of green space in both, as shown on the graphs above.

By extending construction into these areas, the supply of space available for labs would become much more readily available. Despite concerns that this ruins ‘picturesque’ landscapes, this largely isn't the case with more than a third of the green belt dedicated to intensive farming, an environmentally damaging process which leaves landscapes far from scenic.

We're mildly unconvinced by this medical records contract

This strikes us - from an admittedly sketchy knowledge of IT - as being not the right solution:

Silicon Valley billionaires are lining up to bid for a £480m NHS contract to transform the health service’s creaking IT systems into a high tech database.

The so-called NHS Federated Data Platform has attracted a bid from US artificial intelligence company C3.AI, founded by billionaire Thomas Siebel, The Telegraph can reveal.

Moving back one step to what the Federated thing is:

A flagship programme intended to bring down NHS waiting backlogs is to be delayed after becoming mired in bureaucracy.

The £360 million federated data platform is seen as critical to reducing waiting lists, with a record 7.1 million people now waiting for treatment.

When the plans were announced in the spring, health chiefs said that the system would be an “essential enabler to transformational improvements” across the NHS.

Experts have warned that progress in clearing the lists has been set back by chaotic recording systems.

We would not argue that NHS IT is all Ticketty Boo, we are after all rational beings. Greater centralisation would not be our base plan for sorting it out, however. We do recall what happened last time a central solution was tried, £11.5 billion was spent to produce not one, single, usable line of code.

This is also one of those areas where even we agree there’s a role for government. As with the internet itself. But to remind what the government involvement in the internet was - it wasn’t to plan how cat pictures get to you, not how advertising should work, nor even what people should use it for. It was to develop and define the interface.

If the output of some process, machine, effort, whatever, can pass through that TCP/IP interface then it can go on the internet. Any process, machine, effort, whatever that can absorb information through TCP/IP can read the internet and all that’s on it.

Yes, yes, that’s gross simplification to an absurd level. Yet it is also true.

Which is what the reform of NHS IT should be. Define the interface. Information that is in a format that can be read in “this manner” is an acceptable output of any process, machine or effort. Any information that cannot be read in that manner is not allowed. So too with any demand from any machine or process for information as an input. It must be able to accept that in this one specified format. Proprietary methods are allowed, of course they are. But only if any system can both emit and collect all information in the one standardised form as well.

Government’s role is to define and then insist - very forcefully - on that one interface.

We’d go further too, in not allowing anyone in British Government to alter, upgrade, improve or anything else that interface. Pick one - say OpenEMR - and that’s it.

We then gain the best of both worlds. We retain - or even get for the first time - all the glories of markets and competition in how information is to be processed, increasing productivity, lowering costs and all that. We entirely avoid technological lockin by having that open and fixed standard. We also gain an integrated health care IT system - the interface, the portability of the only important thing, the information.

Works for us, now tell us why it doesn’t work in reality?

Lifting the next 800 million out of poverty

How do we go about lifting more people out of poverty?

‘Over the past 40 years, the number of people in China with incomes below US$1.90 per day—the international poverty line as defined by the World Bank to track global extreme poverty—has fallen by close to 800 million. With this, China has accounted for almost 75 percent of the global reduction in the number of people living in extreme poverty.’ (World Bank, 2022)

How do we lift the next 800 million out of poverty? It’ll be tough. But here in the UK there are some simple, effective, and proven policies that I’d like to share with you. Poverty is by no means a solved problem in the West - and I think you’ll be surprised to see the state of it in the UK.

As per the brilliant Our World in Data graph above, the yellow section of the graph indicates a colossal move out of extreme poverty for a huge amount of East Asians - half of which is attributable to China. A colossal move away from absolute destitution never before seen in the history of the World. How the hell did this happen?

I think the single most effective measure at lifting people out of poverty - which has been tried and tested - seems to be a focus on growing the economy; on increasing the amount of products and services we produce. Baking a bigger pie so all can have a bigger slice… supposedly.

So what pro-growth policies did China pursue in order to bring nearly a billion of its people out of poverty? The World Bank tells us that:

‘China’s poverty reduction story since the late 1970s is fundamentally a growth story, complemented, particularly in more recent years, by targeted poverty reduction policies and programs.’ (2022, pg.5)

China opened themselves up to world markets by lessening economic protectionism and mercantilism, developed the necessary infrastructure to compete on the world stage, increased their agricultural productivity, managed urbanisation from rural to urban economic hubs, all of which constituted the free-market led growth side of this achievement. And targeted ‘in-house’ poverty reduction policies constituted the second part, namely investment in education and productivity-increasing skills development.

These growth-led policies helped China to lift 800 million out of poverty. But how do we start to lift the next 800 million people out? The low-hanging fruit (to use a weird but apt phrase) has been picked and it is now tougher to take the next person on the margin out of extreme poverty. And we still have a lot of work to do, globally. Although only 9% of the world now live on the UN’s definition of ‘extreme poverty’ - less than $1.90 - another 53% of the world lives on less than $10 a day. This is far too high a number., as per the OurWorldInData graph below.

But how do the numbers look in the UK? Not great. As of 2017, over 200,000 still live in extreme poverty, defined as living below the International Poverty Line; less than £1.79 ($2.15) a day. Just above the amount of people who live in York are this impoverished in the UK, a high-income G7 country. This is obviously not acceptable - and I thought we’d got rid of extreme poverty in the UK?

200,000 people is around 0.3 per cent of the UK population, which is obviously a very low percentage. But statistics get in the way of reality: these are still people who are struggling and who can ill afford to feed themselves or their families. Some may have mental health problems that make this tougher, etc, but we should look at these cases as challenges to be solved rather than a reason to say: “ah, poverty is pretty low, so we should just be happy with that.”

Unaffordable housing, extortionate childcare costs, high-tax for substandard public services, an increasingly less competitive private sector, and other ailments, seem to have *at the least* worked against further poverty alleviation in the UK.

It seems that there isn’t one single silver bullet here when it comes to growth. But I’ll try and single out some of the more focussed options from here on out. I’m sorry that this first policy on the list could effectively be hundreds of separate ones. I promise the rest of the list isn’t like this…

2) Take the Poorest out of Tax

The UK’s ‘Personal Allowance’ means you can earn up to £12,570 before you are subject to any tax. But I think this personal allowance amount should be higher. As does the Adam Smith Institute, who thinks the specific amount should be pegged to the National Minimum Wage rate, at least. If this was the case,

‘the personal allowance should now be £17,374.50 a year, the equivalent of 37.5 hours a week on the minimum wage of £8.91. Instead, it has remained frozen for the last 10 years. For the average 18-29 year old, we calculate an annual saving of £250 if both income and NI thresholds were indexed by inflation.’ (2022, pg.15)

This would mean those earning the least would have more money in their pocket. I also err on the side of not wanting taxation falling on the poorest in society.

3) Trillion-Dollar Bills on the Sidewalks

We should liberalise immigration. If I’m right, the gains would create so much value that American Economist, Michael Clemens, imagines that it would be like having trillion dollar bills on the sidewalks… sound appealing?

‘The gains to eliminating migration barriers amount to large fractions of world GDP—one or two orders of magnitude larger than the gains from dropping all remaining restrictions on international flows of goods and capital.’ (2011, pg. 83/84)

But won’t this just mean the poorest in our society will face fiercer competition for lower paying jobs? Clemens thinks not:

‘If [...] human capital externalities are real and large [...] it is possible that the depletion of human capital stock via emigration inflicts negative externalities on nonmigrants. However, these externalities have proven difficult to observe [...] and their use to justify policy remains shaky.’ (2011, pg. 90)

Some useful reforms here:

Implement Flexible Right to Buy à la my last blog.

Let residents in each street vote to allow existing houses to be extended upwards or outwards.

Allow development on small areas of the green belt within walking distance of train stations, whilst preserving areas of exceptional beauty.

Liberalise a range of design regulations.

Legalise subletting for social tenants to make better use of existing social housing stock.

The Housing Crisis might just be the single most damaging and far-reaching ailment the UK is suffering with. But how does this help those in poverty?

First-order effects include: an inability to even *think* about getting on the housing ladder as someone in poverty; means those in poverty who might be more economically productive elsewhere cannot live there due to high housing costs.

Second-order effects include: less affordable housing means social housing is more likely to be at capacity usage, meaning those in poverty will wait longer for better housing arrangements; a stronger housing sector means a stronger economy which in turn could increase the opportunities available to those in poverty.

5) Phase in a Negative Income Tax or Basic Income

There is a sizeable literature which believes that just *giving* money to people in poverty might be the most helpful solution to their situation. Those in poverty are so because they lack cash. Yes, other factors are at play, such as mental health and familial wealth. But the primary issue here is that they don’t have enough cash.

A Basic Income (BI) is a payment sent to every citizen (above a certain age, as usually construed) unconditionally - regardless of their wealth. Usually (except for some tougher cases) people in poverty are there because they lack the cash needed to live comfortably and buy their essentials. A BI would seemingly remedy this. Although of course there are questions of how you give those in extreme poverty the cash when most don’t have their own bank accounts.

A Negative Income Tax is, as per Nikhil Woodruff of the PolicyEngine who wrote for us on the topic last week,

‘[…] a very broadly-defined concept with a simple proposition: income tax should start below zero, representing a transfer from the government to the taxpayer.’

‘'When it comes to work incentives, the negative income tax diverges from a policy often described in the same breath: a universal basic income, which provides an unconditional equal cash payment to every person. While a NIT and UBI might sound like the same thing, a UBI doesn’t include any kind of clawback […]'.’

‘This kind of radical egalitarianism necessitates equal treatment of an entire population [combined with] the values of equality and fairness with its most practical implementation: if we share those values, so should we.’

Final thoughts:

Poverty reduction across the World and in the UK has come far and market reforms have lifted hundreds of millions out of poverty.

There is still more for the UK and other countries in the World to do to lift those last people out of poverty-stricken misery.

Effective policy can prove a potent weapon in this task.