This isn't proof of a housing crisis

That we do have a housing problem is obvious. The reason we’ve got one is because the law - the Town and Country Planning Act 1947 and successors - makes it illegal to build houses Britons would like to live in where Britons would like to live. The solution is to blow up that Act, proper blow up, kablooie.

Return to the free market of the 1930s which is the last time that private housebuilding did meet demand.

We all know that.

However, we do also need to point out bad logic and bad evidence:

House-building alone won’t solve the crisis, but it will hugely contribute to some of the most urgent needs in this country – namely the 1.3 million people on English council house waiting lists in need of social rented homes, many of whom are privately renting and sliding into poverty.

Social housing is, by very definition, at less than market price. That there’s a queue for something at less than market price is not a proof of need. It’s a proof of that very human desire to get something on the cheap. If you start selling doughnuts at less than market price you’ll get a queue. Start selling pound coins for 50 p you’ll get a queue. The queue, the waiting list, is proof of below market price, nothing more.

The actual number of people without housing is that 8,000 or so annually (some 4,000 perhaps on any given night) across the country who are rough sleeping.

We cannot use the council or social housing waiting list as proof of the need for housing. We can - and should - use it as proof of that desire to gain something below market price.

Seriously, sell something cheap and what do you expect? That folk won’t line up for it?

Basic income and AI-induced unemployment

Authored by:

Connor Axiotes (Adam Smith Institute)

Nikhil Woodruff (UBI Centre & Policy Engine)

Scott Santens (Humanity Forward)

‘Automation has been transforming the labour market for decades and the development of generative AI is about to kick that into overdrive. We don't even need artificial general intelligence in order for a universal basic income to make sense. Market economies are fuelled by customers with discretionary income to spend, and the more people are unable to afford anything but their basic needs, the harder it is for employers to find customers to sustain their businesses. The need for UBI also goes beyond modernising welfare systems. It could be seen as a rightful dividend to those whose data provided the capital to train large generative transformers like GPT-4, which was all of us’ - Scott Santens, author, Basic Income researcher, and Senior Advisor to Andrew Yang’s Humanity Forward.

* * *

Sam Altman, the CEO of perhaps the most consequential artificial intelligence (AI) lab of the few years, OpenAI, imagines: “Artificial intelligence will create so much wealth that every adult in the United States could be paid $13,500 per year from its windfall as soon as 10 years from now.” He is referring to a Universal Basic Income (UBI) financed from the windfall profits of future AI systems. Altman believes that as AI continues to advance it will become more economically productive than human labour, causing the latter to “fall towards zero.”

Why is AI different?

In order for the price of some labour to fall to zero, AI systems will have to reach a point of generality - meaning the AI can do any task that a human can do but to a superhuman level. Some call this artificial general intelligence (AGI). It is at this point we believe there is a non-negligible chance these systems could replace many domains of both physical (which to some extent has already started happening) and cognitive human labour. It is the chance of the latter occurring which is particularly concerning.

We also do not yet know what emergent properties might pop up which were not intended in the initial design of the AI system, which may present itself post-deployment of an AI system. In addition, some believe an AGI would also display agency. Agency in an AI system would mean an ability to plan and execute its own objectives and goals. Both emerging properties and agency have the potential to make this technology unusually likely to replace cognitive as well as physical labour, as human labour’s comparative advantage of brain power becomes less apparent.

Research by OpenAI in March 2023 found that ‘around 80% of the U.S. workforce could have at least 10% of their work tasks affected by the introduction of LLMs, while approximately 19% of workers may see at least 50% of their tasks impacted.’ Gulp. Their paper examines the potential labour market impact of large language models (LLMs), like OpenAI's GPT, focusing on the tasks they can perform and their implications for employment and wages.

The authors emphasise that while LLMs have demonstrated remarkable capabilities, their real-world applications and overall impact on the labour market are still not fully understood. They work out that LLMs have the potential to directly impact approximately 32% of the US labour market, primarily in occupations that involve information processing and communication tasks.

But what if we are wrong... again? Technology doesn’t seem to cause lasting unemployment effects?

It seems as though transformative technologies have always complemented labour even if shorter-term employment shocks were experienced. Even when technology had made people unemployed in a specific sector, that pesky invisible hand of the market seemed to ensure industry elsewhere popped up and human labour was never very far from a job. So why would any other transformative technology be any different? Are we just another group of Luddite’s heading for the same egg-on-our-face fate?

We think this time it might be different

Due to the aforementioned properties and agency of AGI, we believe this time it will be different. Mainly because it will touch physical and cognitive labour with such efficiency, and leave humans with little comparative advantage with which to earn a proper market wage.

And so, we proceed in this piece under the assumption that an AGI with superhuman abilities in all human tasks - and the agency to plan and execute its own strategies - will, we believe, have significant sticky unemployment effects on lower skilled occupations as a conservative minimum estimate. We assume the economy is static and no other jobs can replace - with a liveable income - the jobs formerly lost by the now relatively (compared to the AGIs) economically unproductive labour.

And so the question arises, how would a Government go about finding a policy that might mitigate these effects? At the Adam Smith Institute, we have advocated for this policy for years, initially with the aim of simplifying the welfare system and for being a more effective and less regressive form of redistribution: a basic income.

A cumbersome state and an agile problem

The difficulty with ensuring that the state is responsive to the impacts of AI is largely because we do not yet know in what form AI’s disruption will take. If it is to be large-scale unemployment, strengthened unemployment insurance might appear a natural response. Or if employment incomes fall but jobs remain, in-work benefits might bear the strain.

But both of these countermeasures have their weaknesses. Interacting with the bureaucracy around modern welfare systems is time-consuming and undignified - so much so that around a quarter of eligible recipients never make it through. Ironically, this failure to target intended recipients is seen almost exclusively in programs that impose income eligibility conditions in the very name of ‘targeting’: unconditional cash programs like the Child Benefit have almost perfect accuracy in reaching their targets.

Unconditional cash therefore (or specifically: a universal basic income) may represent the only mechanism to ensure income stability for those who need it, whatever form the AI intervention takes. Critics of UBI often point to the high cost of the cash payments, and the substantial broad-based rises in taxes we’d need to fund them, as disqualifying factors. But the notion that the current welfare system avoids this is an illusion.

Many also recoil at the notion of a 50 percent flat tax, but see no issue with our 55 percent rate on income paid by some Universal Credit recipients. Means-tested benefits are not the magically targeted free-lunch that they might appear to be: they are by definition equivalent unconditional cash payments combined with a very high tax rate paid exclusively by some welfare recipients.

If the government proposed a large UBI funded by raising the National Insurance main tax rate from 12 percent to 55 percent, public support might not be very forthcoming. But that’s almost a mirror image of what Universal Credit is. The only difference is that UBI is administratively far more efficient.

But if a UBI were to be introduced, this should only be done with the abolition of much of the current welfare and benefit system in the UK and over a period of 5 to 10 years; total benefit spending is forecast to be £255 billion in 2023-24.

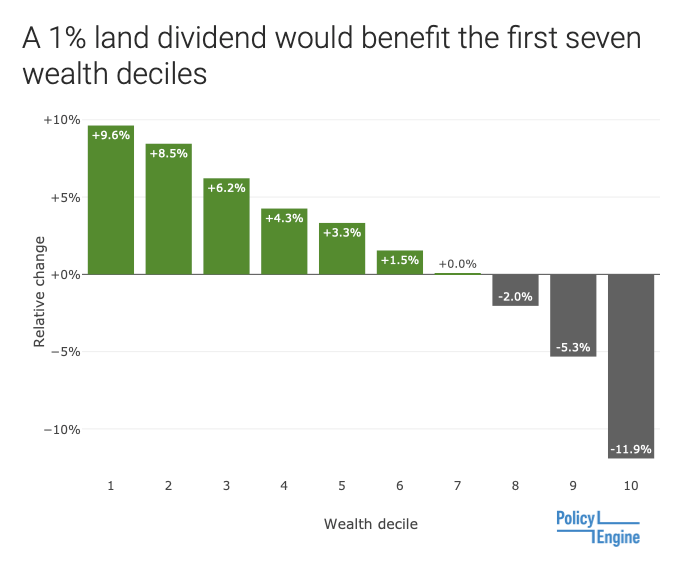

Broad tax rises on income could be one way to fund these cash payments, though critics would rightly point to negative labour supply responses. Taxes on natural commons could present an alternative: a 1% land value tax could raise enough to fund a £24 per week dividend.

(Impact of a 1% land value tax funding a £24 per week UBI. Source: PolicyEngine)

Alternatively, a price on carbon could raise enough revenue to fund cash transfers. Distributing the revenue as an equal dividend would lower poverty rates for children, adults and seniors alike.

(Impact of a £100 per tonne carbon tax funding an £11 per week UBI. Source: PolicyEngine)

Both of these have their own political challenges: the asset-rich cash-poor older generation is a significant bloc, and carbon taxes, like other consumption taxes, have a more regressive impact than income taxes when measured as a percentage of income. But in all of these tax bases, cash is more progressive than the tax base is regressive: a tax-funded UBI nearly always reduces poverty.

Conclusion

We are pretty confident that future AGI systems will have superhuman labour abilities, generality, and agency.

We are also pretty confident that upon the creation of such an AGI, we will see a significant structural and sticky proportion of human labour unemployed of the likes we have not seen with other transformative technologies.

At such a time, the UK might seek to address this novel issue through the introduction of a UBI. We should start preparing for this scenario sooner rather than later, to allow the Department for Work and Pensions to get up to speed with the policy detail.

* * *

Previous Basic Income (or NIT) research by the Adam Smith Institute

Basic Income Around the World, (2018), https://www.adamsmith.org/news/rising-evidence-basic-income

Nine Arguments Against Basic Income Debunked, (2018), https://www.adamsmith.org/blog/nine-arguments-against-a-basic-income-system-debunked

Schrodinger’s Basic Income: what does the Finnish UBI experiment really show, (2019), https://www.adamsmith.org/blog/schrdingers-basic-income-what-does-the-finnish-ubi-experiment-really-show

Welfare shouldn’t be complicated, (2023), https://www.adamsmith.org/blog/welfare-shouldnt-be-complicated

Lifting the next 800 million people out of poverty, (2023), https://www.adamsmith.org/blog/liftingpeopleoutofpoverty

So the chicken market seems to be working just perfectly then

We’re told that chicken farmers are having a very hard time of it. To which the correct response is good:

‘It’s absolutely dire’: why UK chicken farmers want to call it a day

Bird flu, higher costs and the rise of meat-free options are pushing poultry producers to reduce flocks or give up entirely

We desire some system that can balance out these changes. The cost of producing something goes up - OK. So that means that fewer people will demand that thing as the price necessarily rises. Or, as here, people aren’t willing to pay that higher price and so demand falls. Equally, we’ve substitutes arriving. Both those plant based chicken alternatives and also presumably some sort of expansion of vegans, vegetarians and other dietary kinks. So, demand falls again.

We require some system to deal with these variations. We’ve got one, that price system. Things change and chicken farmers go bust. Not pleasant, of course, but it is the only way anyone has ever found to keep that supply and demand balance.

Of course, because it works The Guardian complains about it. But then that’s pretty normal too.

The World Economic Forum isn't quite right here

Technology and slow economic growth will destroy 14 million jobs around the world by 2027 with secretaries and bank workers facing the biggest losses, economists have warned.

Nearly a quarter of jobs around the world will change in the next four years as tech and the green transition disrupt labour markets, according to new research by the World Economic Forum.

Well, yes, that will happen.

Digitisation will also create massive labour market churn. Nearly half of an individual worker’s skills will need to be updated for the modern labour force.

In the UK, more than a fifth (21pc) of all jobs will change. This will be slightly lower than the 23pc global average.

That too. But the not quite right bit is to think that this is anything unusual. When, in fact, this always happens. This is just normality.

The bit that people forget. Some 10% of all jobs in the economy - so, for Britain, about 3 million - are destroyed each year. Some 10% of all jobs are newly created each year too. Unemployment is the stock of people who get stuck in that state as part of that flow.

So, over the 4 years to 2027 we expect 40% of all British jobs to disappear and be recreated. That’s just normality.

This is also how technological change happens - each new job is going to be slightly different from each old one. It’s not that people leap from being a bank worker to a ballet dancer, but that each job change will be a modest shift - which might well result in one less bank worker and one more ballet dancer but it will be the whole process that achieves that, not one single jete from the counter to the stage.

So the WEF is correct, this is going to happen, but not quite right in that they seem to think it’s anything other than business as entirely usual.

The example of the Aston Martin Cygnet

One of the truly stupid transport options of recent decades is the Aston Martin Cygnet. Aston, as we know, is a car brand with a history of going bust (8 times so far we believe) while attempting to make large engined sports cars for the discerning. The authorities, in their wisdom, decided that emissions should be decided across the fleets sold by a manufacturer. So, someone who only made, as specialists, large engined cars would be driven out of business. Thus the production of a 1.33 litre car to lower those average emissions.

Given the insanity of the outcome here obviously the authorities would not impose such heinously stupid targets again, would they?

At least 22 per cent of the cars manufacturers sell next year will have to be electric – or they could face fines of up to £15,000 per car they miss their target by.

That’s if the latest government proposals get the go ahead. Ministers have today announced proposed new targets as part of a major green agenda which details tough goals and punitive measures for car makers.

Har, har, har. gotcha there. For of course what the authorities have done is look at the Cygnet and insist that we should have much more of that.

When we all hope that people will learn from their mistakes that wish is that people will not repeat them - instead of using error as the template for the next action. But that’s not how government works, is it?

But Vandana Shiva's ideas don't work

One of the advantages of the market based economic system is that people try out all sorts of things. We can then look at the results of what they’ve done, copy those that work well and abandon those that don’t. Persisting in advocating those that don’t work is often referred to as religion - or perhaps Einstein’s definition of insanity, repeating the same mistakes and expecting a different result.

All of which is something to keep in mind when considering Vandana Shiva’s approach to farming. The Guardian provides something of a hagiography - to repeat the allusion to religion - in this interview.

The formidable Indian environmentalist discusses her 50-year struggle to protect seeds and farmers from the ‘poison cartel’ of corporate agriculture

Well, yes, we can see why fight The Man would appeal to those with comfy office jobs and who have never had to struggle with the soil for their daily bread.

For Shiva, the global crisis facing agriculture will not be solved by the “poison cartel” nor a continuation of fossil fuel-guzzling, industrialised farming, but instead a return to local, small-scale farming no longer reliant on agrochemicals.

Local, small-scale farming has another name - peasantry. To remove technology - and capitalism, globalisation and markets - from farming would be to condemn all of humanity to permanent peasantry. We think that’s a bad idea.

But more than that, the thing The Guardian doesn’t mention. Shiva’s ideas have been tried. Just recently, in Sri Lanka. She herself has said so. As many have noted the results were, umm, not good. Like the collapse of yields, imminent starvation and the ruination of the entire economy, the bankruptcy of the State.

We do think it would have been useful for The Guardian to point this out. The ideas have been tried and they don’t work. But then those with the comfy office jobs always do think that they’ll retain those in that New World Order, that it’ll not be them sent out to be that new peasantry. Kip Esquire’s Law is one of those ideas that has been tested and found to be true.

We're fine with this Greedflation idea, no, really

It’s all the capitalists trying to rip us off:

And there is more and more evidence that aggressive profit-seeking has contributed significantly to the inflation surge. Research released in March by the trade union Unite showed that for the 350 largest companies listed on the London Stock Exchange, “Profit margins for the first half of 2022 were 89% higher than in the same period in 2019.”

We would note more recent evidence too:

Britain’s second largest supermarket has reported a fall in annual pre-tax profits as it revealed that it had spent more than £560 million on keeping its prices low over the past two years.

To explain all of this we can - even should - look at the original report from Unite which makes that allegation of greedflation.

Economic analysis: Five channels of profiteering

“Free market” economic theory says that prices and profits should come down as firms compete and undercut each other. But across a whole range of markets, this has been failing to happen. The broken economy provides plenty of opportunities for firms to profiteer – that is, take advantage of a crisis.

Specifically, we identify five main economic channels of profiteering:

1. Supply crunch. After a supply chain shock, demand chases reduced supply – this allows companies to push up prices and profits. (Examples: food crops hit

by widespread droughts; semiconductors hit by pandemic production halt, raw material shortages and trade wars.)

2. Demand jump. An increase in demand for a good, while supply remains

constrained, allows companies to lift prices. (Examples: many consumer

products at the end of the pandemic.)

3. Market windfall. Centralised market pricing structures help companies score “windfall” profits – where a market-wide price jumps due to factors unrelated to many companies’ costs. (Examples: oil and gas, wholesale electricity

market.)

4. Market concentration (oligopoly). Where a few large companies dominate

an industry, they can have greater power to increase mark-ups. (E.g., oil and

gas, shipping, ports, supermarkets.)

5. State-licensed monopolies. In some key industries, companies are granted government concessions which give them major power to set prices, encouraged by failing regulation. (E.g., North Sea oil fields, electricity and gas distribution networks, other privatised utilities.)

We’d argue with 4) especially as it applies to supermarkets. Not just that fall in Sainsbury’s latest profits. But the simple fact that margins have collapsed over the past 25 years. Around the turn of the century British supermarkets made perhaps 6% of sales. Now it’s about 2 to 2.5%. What changed was the irruption of Aldi and Lidl - yes, it is that recent at scale. And yes this does prove that markets and competition work to restrict profit making. It might take time, but it works.

Actual oligopolies, with market power, or those state backed monopolies, of course we should kill them off. We’re not going to say different about that. Monopolies are Bad, M’Kay? What they’re calling “market windfall” is just marginal pricing. Of course the price across the market reflects the production price of the last unit to be produced. How does anyone think supply and demand works if not in that manner?

But it’s the 1) and 2) there which needs to be emphasised. Sure, supply and or demand change, prices and profits do. Sure. It’s what happens next that matters. The greedy capitalists see those luvverly profits being made and change their own production patterns. To go steal some of those luvverly profits off the other capitalists. This is how supply increases - or shrinks of course - in order to meet that change in demand. Which is what brings prices back down again as supply and demand move to meet each other.

This is how we gain the resource reallocation to meet those changes in supply and or demand. This is actually the point of the price system itself plus a market with free entry and exit. This is what it’s all about.

It doesn’t work overnight, to be sure, but it does so faster than any other method anyone’s ever discovered let alone tried.

Unite are actually complaining that prices - therefore profits - change when supply and or demand do. When changes in the profits from changing prices as a result of supply and demand changes are the very point of the system in the first place. For they’re the incentives to go change supply and or demand in order to moderate price changes.

That is, they’ve either entirely misunderstood the world they inhabit or are just looking for something to whine about. With Unite we’re not sure but of course that first quote comes from The Guardian - that’s definitely the second reason there. What is a comment page without a whine on it?

The problem is government just never does stop spending, does it?

If there are fewer children then we require fewer schools, right?

Failing schools with tumbling pupil numbers will be “propped up” by the taxpayer under plans to hand them extra cash to stay open.

Har, har har, no, don’t be silly. That’s not the way it works in the slightest. If we require less schooling to take place then what government is going to do is subsidise schooling more. This would of course be one of the advantages of moving to a pure voucher system, as in Sweden. Government expenditure upon schools will be defined and limited by the number of children who need schooling.

But there’s also that larger issue to consider. Which is that the really grand difference between capitalism ‘n’ markets and government is that the capitalism ‘n’ markets system has within it its own culling system. It operates naturally, without requiring any positive action. If something is no longer worth doing - that is, the resources to do it cost more than the benefit that can be captured from doing it - then the people doing that thing go bust and are removed from the system. They also stop wasting resources on those things no longer worth doing.

This is not true of railway systems when run by government - vide HS2. It’s not true of blast furnaces when there’s even a sniff of subsidy available. Simply because we do recycle much more steel these days we require fewer blast furnaces. Is that actually happening? Nope, not here it isn’t, everyone’s standing around with their hands out instead.

If we require fewer schools because there are fewer children who need educating then we should close schools. Is that what government’s doing? No - which is the argument against government running schools, isn’t it.

This all sounds a bit colonialist to us - thought we'd stopped doing that?

There was indeed a considerable period of history in which we pinkish European types told most of the rest of the world - poorer and possibly slightly differently tinted - what to do. We then started calling that colonialism a bad idea and so stopped doing it. Or, at least, we thought we’d all stopped doing that:

Pesticides banned in the EU because of their links to human health risks are being exported and used on farms in Brazil supplying Nestlé, an investigation has revealed.

Europe is home to some of the world’s biggest and most profitable chemical companies, including the Swiss-based Syngenta and the German multinationals BASF and Bayer.

But a number of the pesticides and fungicides they produce have been banned by European health officials after they were linked to cancer, reproductive problems and neurodegenerative diseases.

Despite the ban, millions of pounds worth of the products are still being exported to Brazil, where they are used on farms that supply the international sugar market, according to a new investigation by Lighthouse Reports and Repórter Brasil.

Brazil has been independent for over two centuries now. Brazil gets to make up its own mind as to how it wishes to regulate pesticides - and herbicides, fungicides and the rest.

It’s certainly possible to imagine seasons why different decisions might be reached. As a poorer country perhaps the risk/reward trade off is different? Possibly the climate leads to greater problems that must be solved? Or maybe, and we know this might come as a shock, Brazilians have a different view of the good life from the more puritanical Europeans?

About the only thing that doesn’t seem to have changed here is that pinkish Europeans are telling Johnny Foreigner what must be done. Even using the same justification - it’s for your own good you know.

We really did think we’d all agreed to stop doing that. So, why haven’t we?

Adam Smith wrote another book?

Adam Smith (1723-1790) is best known today for his pioneering work of economics, The Wealth of Nations (1776). But in fact, he soared to international fame earlier, with The Theory of Moral Sentiments, published on this day in 1759.

It was a sensation. Moralists had struggled for centuries to work out what it was that made some actions morally good and others morally bad. To Clerics, the answer was obvious: The Word of God. And believers relied on the Clerics’ moral authority to explain exactly what that meant.

Sceptics, on the other hand, speculated about whether we had a sixth sense, a ‘moral sense’ like sight or smell, that would guide us towards the good. And there were many other unsatisfactory ideas.

Smith’s breakthrough was to see our moral judgements as part of our social psychology. As social beings, he argued, we have a natural ‘sympathy’ (today we would say ‘empathy’) for others. That empathy prompts us to adjust and moderate our behaviour in ways that please others. That is the basis of our moral judgements and what we understand by virtue.

It also promotes social harmony. Smith was not sure why such socially beneficial behaviour should prevail over any other. He put it down to providence. Today — thanks to Charles Darwin’s The Origin Of Species, published a century after Smith’s book, we would attribute it to evolution.

The Theory of Moral Sentiments became a best seller and it so impressed Charles Townsend, a leading intellectual and government minister, that he promptly hired Smith, on a salary of £300 a year for life, to be tutor to his stepson, the teenage Duke of Buccleuch.

To a Glasgow academic, it was a fortune—and it gave Smith the independence and experience to start writing the work for which he is best remembered today: The Wealth of Nations.