But why shouldn't climate change be a political issue?

We have an awful lot of people trying to insist that climate change simply should not be a political issue. John Harris is just one of them:

In the UK, unfortunately, the past 48 hours has seen a political story whose parochialist absurdity is off the scale: Conservative voices undermining the fragile cross-party consensus on reaching net zero by 2050 and calling for many of the UK’s tilts at climate action to be either slowed or stopped. The reason? The results of three parliamentary byelections – and, in particular, the views of 13,965 Conservative voters in the outer London suburbs.

But climate change is the very essence of a political issue, something that has to be decided by politics.

No, leave aside the question of whether it is happening, even that of whether anything should be done about it. Stick with just the one point - if we’re to do something what is it that we should do?

Net Zero? A carbon tax at the social cost of carbon? As it happens the science prefers the second rather than the first there. So no one can use “but the science” to decide on the first.

But very much more importantly there’s a big political question here. Britons are being told to carry the cost of lower emissions so that others may gain the benefits of lower emissions. This is something that can only be done with the acquiescence of Britons. Elections are how we decide those things. What we do about climate change is the very essence of what a political issue is. Therefore rather than no politics about climate change we must have lots and lots more.

This is before a rather more sarcastic observation we’d like to make. The same people - largely that is - who argue against this democracy about climate change are those who shout for a “more democratic economy”. Surely that couldn’t be because they think the demos would vote for their economic policies but against their climate ones now, could it?

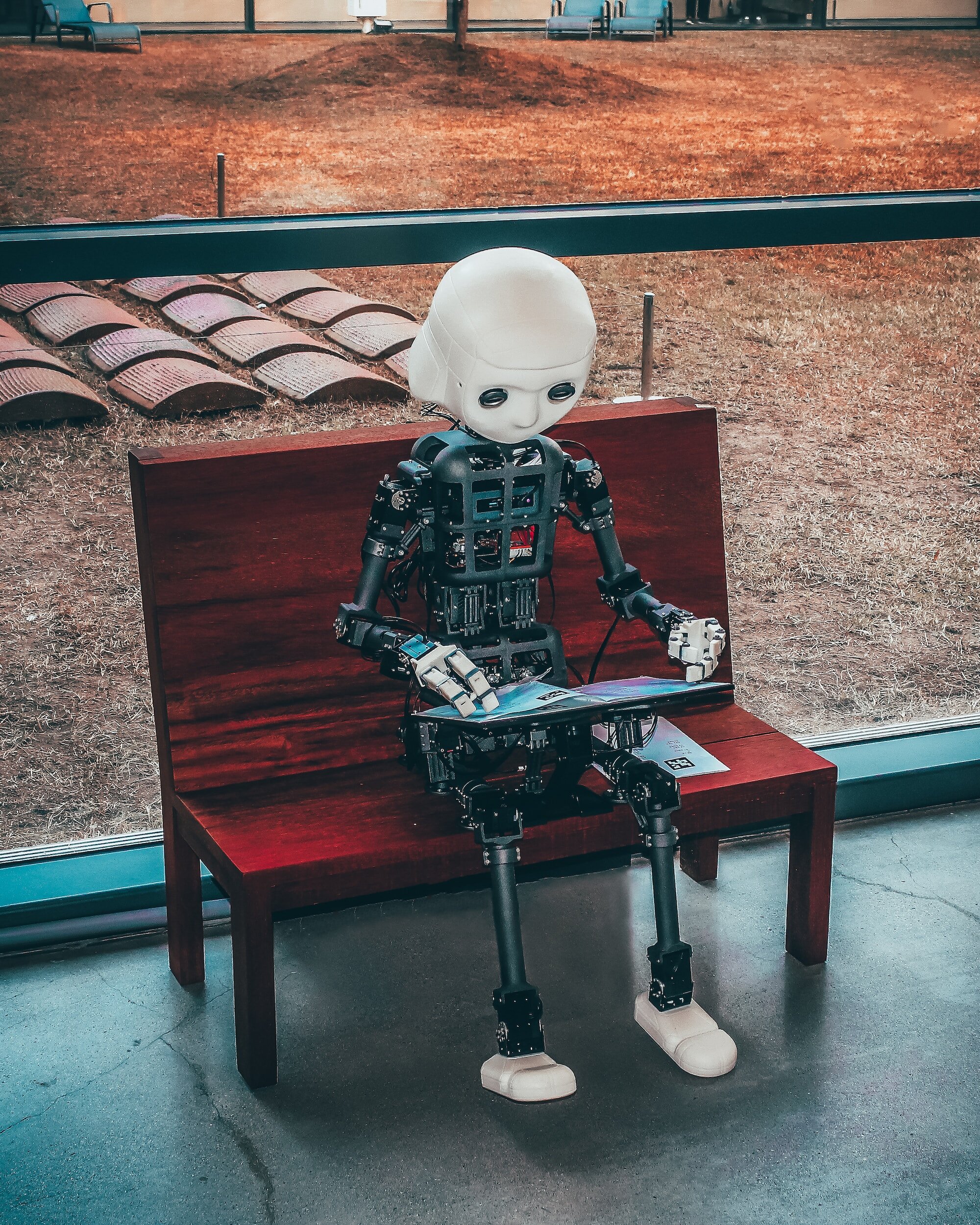

We literally just turned sand into intelligence

It’s a common enough claim, echoing Boulding. Infinite growth on a finite planet is the dream of madmen and economists. To which an elegant response. One so good that we wish we’d come up with it but as we didn’t we’ll simply steal it.

“We literally just turned sand into intelligence”

Just to be completist, that’s from “gfodor.id”.

Us cornucopians and growthists agree, entirely, that there’re a limited number of atoms on the planet. Going into space doesn’t remove the limit, just expands it. The same is true of energy and everything else physical. Yes, you’re right, the universe has limits (unless the infinite universists are right but let’s not go there). Therefore infinite physical growth in a physically limited universe is not possible.

Good, well done.

One line of attack on that idea is whether those limits are relevant at present - to either the size of our current economy or anything that it will get to in any time scale we should want to care about. We do indeed face limits - CO2 in the atmosphere being one, fish in the sea perhaps one more immediate although to be fair opinions differ there - over the relevant immediacies. We worry more about the fish but that’s just us.

But put that aside and move to something more basic. The economic growth that is being talked about is that in GDP. Something we keep having arguments about as we attempt to enlighten people. GDP is not the number, weight, volume, of things done to physical items. It’s the value added. Not even the value added to the number, weight or volume of physical things but the value added full stop. Finally, it’s not the number, weight, or volume of things that are done to. It’s the value added.

Within this are two different but related observations. One is that usual ecological economics insistence that we should work toward qualitative growth, not quantitative. Well, OK, but to the extent that qualitative growth is the addition of value that’s already included in GDP growth. Because that’s what we’re measuring, value added.

The other again, OK, we should prefer the one q to the other q. How do we encourage this? A possibly slightly extreme but supportable analysis of the planned and socialist economies is that they managed no total factor productivity growth over their entire lifetimes. The Soviet Union, from 1917 to 1991 managed not one whit of this. There was economic growth, most certainly - but all of it was quantitative. To gain one more unit of GDP they needed one more unit of inputs. They grew because they mined more, worked more, grew more, without improving the efficiency with which they did any of those things. Another equally standard analysis is that the 20th century growth of the market economies was about 80% TFP improvements and about 20% increases in inputs. (BTW, these estimates are, respectively, sourced from Krugman and Solow, neither of them known as neoliberal extremists like ourselves. Also both Nobel Laureates, unlike ourselves. So far).

So we can argue that even if the ecological are right, we should prefer, deliberately and with malice aforethought, through policy that qualitative not quantitative growth then we should be preferring market, not planned economies. Entirely the opposite of what is argued but then that’s politics for you.

And here we have an elegant exemplar of that basic contention. Sand is now writing novels. To the extent that they’re good novels this is value addition. Given the average novel they are value addition too.

And yes, we know, there really are people out there claiming that we’re running out of sand. But not that sort of sand that is being turned into computer chips, we assure you we’re not.

Are there limits to physical growth on a physically limited planet? Sure, and obviously. But given that the measure of the economy is value added the limit to economic growth is the knowledge of how to add value.

GDP is value added. The limit to GDP is the knowledge of how to add value.

At which point we’d remind you of this observation which we wish we had come up with but as we didn’t we’ll just steal it:

We literally just turned sand into intelligence

QED

The current value of Afghanistan's lithium reserves is zero.

In fact, as the Pentagon itself quotes us as saying, Afghanistan’s mineral reserves are worth bupkiss.

Which makes this Washington Post report more than a little suspect.

Rich lode of EV metals could boost Taliban and its new Chinese partners

The Pentagon dubbed Afghanistan ‘the Saudi Arabia of lithium.’ Now, it is American rivals that are angling to exploit those coveted reserves.

No. Really, just no.

But now, in a great twist of modern Afghan history, it is the Taliban — which overthrew the U.S.-backed government two years ago — that is finally looking to exploit those vast lithium reserves,

Again, no. There are no lithium reserves in Afghanistan. Therefore the value of lithium reserves in Afghanistan is zero.

A mineral reserve is a specific thing, a phrase that has a meaning in the technical jargon. It means that we - some member of the species, perhaps some group of such, homo sapiens sapiens - has drilled, measured and weighed the deposit, shown that it can be extracted using current technology, shown that doing so will make a profit at current prices and also has the licences to be legally allowed to do so. As no licences have been issued - let alone any of the other work - there are no lithium reserves in Afghanistan. Therefore the value of lithium reserves in Afghanistan is zero.

This is all a repeat of a grand mistake that has been made for a long time now. This one:

A decade earlier, the U.S. Defense Department, guided by the surveys of American government geologists, concluded that the vast wealth of lithium and other minerals buried in Afghanistan might be worth $1 trillion, more than enough to prop up the country’s fragile government. In a 2010 memo, the Pentagon’s Task Force for Business and Stability Operations, which examined Afghanistan’s development potential, dubbed the country the “Saudi Arabia of lithium.” A year later, the U.S. Geological Survey published a map showing the location of major deposits and highlighted the magnitude of the underground wealth, saying Afghanistan “could be considered as the world’s recognized future principal source of lithium.”

Really, just no. We explained this here in 2010, at The Register. We explained it again in 2017 at Forbes.

There are lithium deposits in Afghanistan, no one has any doubt about that. But there are lithium deposits near everywhere. It’s a common element. The value of spodumene (the lithium-containing mineral being talked about) at the end of a two goat track is about that zero even when extracted. The artisanal miners are talking of having been able to sell it at 50 cents a kg a year or more back when lithium prices were at their peak. Which is about right, $600 a tonne today (much lower than that 18 months back) for direct shipping ore - delivered.

But don’t just take our word for it. Or rather, take our word but filtered through the intelligence services of the Pentagon. For there is this, from SIGAR (“Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction"):

More recently, and more colloquially, the British economic writer Tim Worstall commented on the U.S. government’s view of Afghanistan’s large deposits of iron, copper, and lithium: “The problem with all of this is that those minerals are worth nothing. Just bupkis.” The reason for his assertion: “The value of a mineral deposit is not the value of the metal once it has been extracted. It’s the value of the metal extracted minus the costs of doing the extraction. And as a good-enough rough guess the costs of extracting those minerals in Afghanistan will be higher than the value of the metals once extracted. That is, the deposits have no economic value”—“As we can tell,” he adds, “from the fact that no one is lining up to pay for them”

Afghanistan has lots and lots of lovely rocks. Of mineral reserves it has not a shred nor a scrap. It is indeed entirely possible that some of those rocks will one day become mineral reserves. But the net present value of those rocks is, as minerals, something around zero. The idea that they’re worth $1 trillion is truly away with the faieries - the result of not understanding even the first bedrock* principles of the subject under discussion.

Even the Pentagon now understands this. And if it’s possible to get military intelligence to understand an idea then the rest of us should be able grasp it too.

*Ahaha. Sorry, couldn't resist.

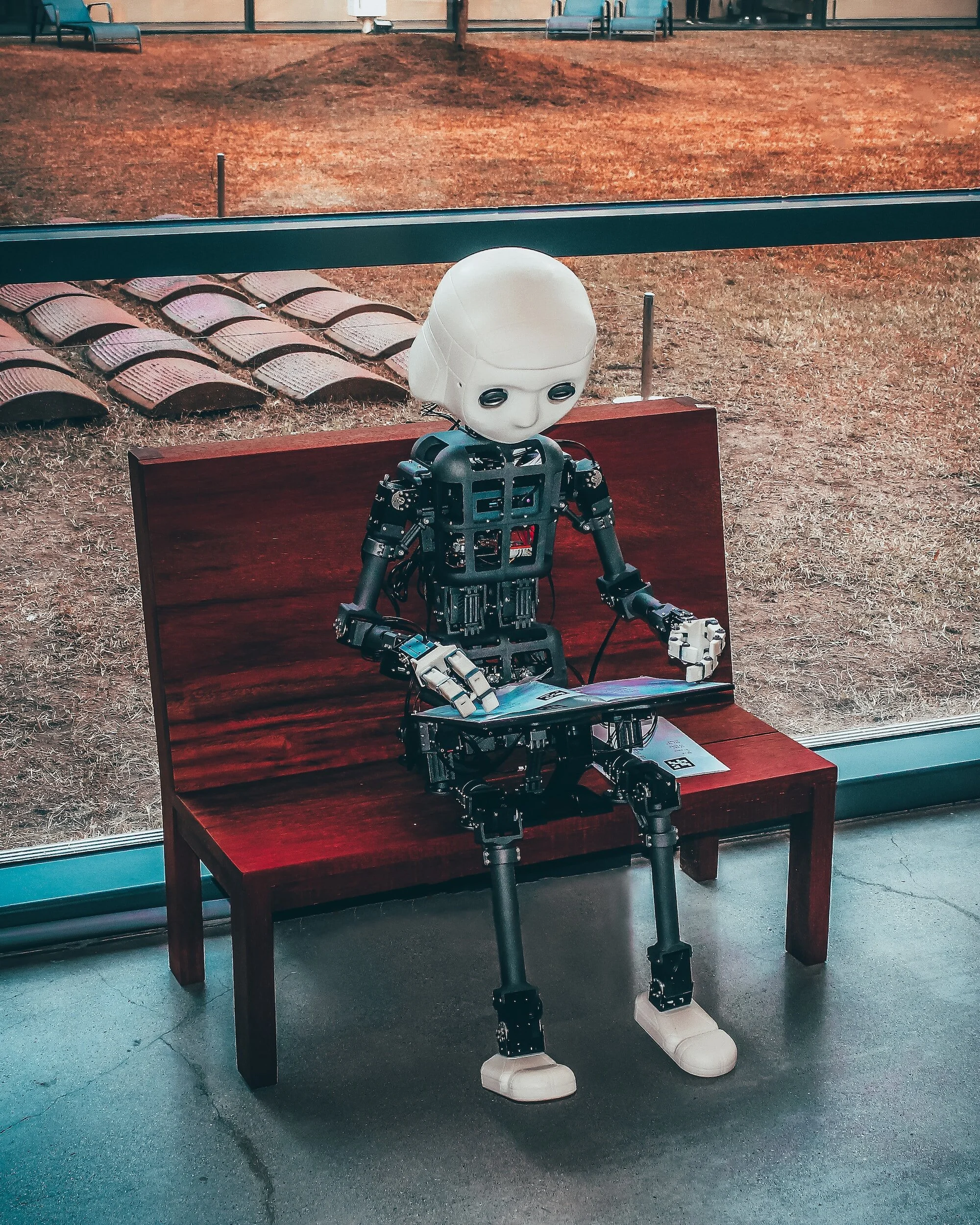

We can't regulate if we don't know

This is from the US but the idea is common enough here: .

@POTUS: Realizing the promise of AI by managing the risks is going to require new laws, regulations, and oversight.

In the weeks ahead I’m going to continue to take executive action to help America lead the way toward responsible innovation.

This is impossible. We do not know what AI will be useful for. We do not know what it can actually do, what we want done, better than other ways of doing that thing (OK, other than writing C grade essays at GCSE level). We also do not know what might be a problem with what AI can do. We don’t know the benefits, we don’t know the risks.

We face, that is, radical uncertainty. So it’s impossible for us to plan anything. For planning assumes that we have an idea of the cost/benefit analysis so that we can say do that, don’t do t’other. And if we are radically uncertain then we can’t do that, can we?

We have to experiment to find out that is - which is what the market process is, experimentation to find out. Where is that confluence between what this new technology can do and the list of things that people want done?

Given that the people developing AI have no clear knowledge here, we the potential consumers have no idea then how are bureaucrats - armed as they are with the wrong incentives to boot - going to have a fogged clue?

We do already have those general and necessary rules - don’t kill people, don’t poison them, no libel, no incitement to violence and all the other rules that make up a civilised society. But we can’t go any further than that general structure because we simply do not know.

This is something the would be planners never will grasp, let alone admit. You can’t plan uncertainty. The lack of knowledge means that you cannot direct activity. It’s exactly when we don’t know that we’ve got to leave well alone so that we can find out from the undirected experimentation of market processes.

They’re using as their excuse to intervene the exact reason they should be doing absolutely nothing.

What’s AI gonna do? Dunno. So, how you goin’ to plan it then?

Greenpeace thinks planes are 30 times better than trains

Not that Greenpeace actually puts it that way, they manage to get it the wrong way around:

Flying in Europe up to 30 times cheaper than train, says Greenpeace

The report is here and the facts are pretty much what we’d expect. Train routes of a couple of hours - Zurich Vienna say, Lisbon Porto, are highly competitive with flying. Longer distances the flight seems to become progressively cheaper.

Of course, Greenpeace then gets this the wrong way around. They think that rail should be massively subsidised so as to make it cheaper for consumers than flying. Which is really very odd indeed. Because if flying is cheaper then it must be true that flying uses fewer resources than trains.

Especially since European rail systems are all massively subsidised already and flying isn’t - indeed it’s done by profit making companies. Sure, there’s the not having to pay tax on emissions - but even that’s not quite true. Air Passenger Duty on flights from the UK is deliberately set at a rate to cover that. Flying’s still cheaper. And, yes, British trains at least pay red diesel prices, largely untaxed that is.

One aspect of this is that a train is an expensive piece of kit, just like a plane is. So, if it takes 24 hours to get somewhere - cross-Europe can do by rail - then that expensive piece of kit is tied up transporting that one load for 24 hours. Instead of the three hours perhaps for a plane.

But those sorts of details we simply don’t need to worry about. We’ve prices to inform us. All resources used in doing something are in the price. More expensive forms of transport therefore use more resources. Trains use more resources than planes because they’re more expensive.

And Greenpeace, in the name of saving resources, wants to get us all out of planes and into trains. Yes, of course we know Greenpeace was set up by addled hippies. But we weren’t sure they were this addled. Let’s expand resource use to save resources? That’s some strong acid you’re using there.

AI is going to kill all the jobs - isn't that wonderful?

An interesting little bit of research about an entire sector of jobs that really were killed off by automation - telephone operators.

Telephone operation was among the most common jobs for young American women in the early

1900s. Between 1920 and 1940, AT&T adopted mechanical switching technology in over half of

the U.S. telephone network, replacing manual operation. Although automation eliminated most of

these jobs, it did not affect future cohorts’ overall employment: the decline in operators was

counteracted by reinstating demand in middle-skill clerical jobs and lower-skill service jobs.

Using a new genealogy-based census-linking method, we show that incumbent telephone

operators were most impacted, and a decade later more likely to be in lower-paying occupations

or have left the labor force

AI taking all the jobs (or more likely, many in some sectors, few in others) is not a problem over time. Mechanisation works just like us free marketeers say it does over those long periods of time. Simply because the young grow up and do other things other than that which has now been automated.

Where there is a potential problem is in those thoroughly trained in that old thing now gone and don’t or can’t retrain across to those other, newer, things that are now to be done.

Another way to put this is that it is the speed of transition that matters. A transition that takes place over a working lifetime doesn’t matter at all. One that happens tomorrow might well do.

But that’s not the end of the story. There always is jobs churn in the economy anyway. And it’s much, much, higher than people generally think it is. A rough guide is that 10% of all jobs in the economy are killed off each year, another 10% newly created each year. There’s near always some technological shift between the old and the new as well. Unemployment is not this flow from job to job, the unemployment number we see quoted is those who get stuck in this position of no job, not those moving across from old to new.

At which point, if the job destruction/creation rate, as a result of the new technology, rises substantially above that normal societal rate then perhaps we might actually have that claimed problem of technological unemployment. If not we won’t.

Currently the management consultancy predictions are of the order that AI endangers 40% of jobs over the next decade or two. A period of time in which we expect 100 to 200% of all jobs to be destroyed anyway. This is not to say that there’s going to be no problem here - there are always problems with humans. Rather, the jobs inferno about to be brought about by AI seems well within the usual limits of the jobs inferno that always does exist within the economy. We might even have marginal problems but we’ve not got a large and systemic one.

Another way to put this is that we’ve already got the systems in place to deal with the problem - a free market in labour and an unemployment system for those who get stuck, temporarily, in the transition. What else do we need?

Unleashing Britain's Potential: The Power of a Modern Great Exhibition

In 1851, the United Kingdom astounded the world with the Great Exhibition—an iconic showcase of innovation, industry, and cultural exchange. Dr Anton Howes of The Entrepreneurs Network has made a case showing how, in the 21st century, a modern-day Great Exhibition has the potential to reaffirm Britain's commitment to new technology and solidify its position as a global leader. By hosting such an event, the UK can harness its strengths, inspire innovation, attract investment, and foster international collaboration.

A modern Great Exhibition would serve as a catalyst for innovation, igniting the imaginations of entrepreneurs, scientists, and inventors from across the globe. By providing a platform for showcasing cutting-edge technologies and ideas, the UK can inspire a new wave of innovation and creativity. This exhibition could highlight the country's expertise in areas such as artificial intelligence, biotechnology, renewable energy, and advanced manufacturing, encouraging breakthroughs and fostering collaboration between academia, industry, and startups.

Hosting a Great Exhibition would enable the UK to position itself as a global leader in new technology. By featuring groundbreaking inventions, research, and development, the UK can demonstrate its commitment to pushing the boundaries of progress. This exhibition could emphasize the UK's prowess in emerging fields, allowing the world to witness firsthand the nation's capacity to embrace technological advancements and drive positive change. As The Entrepreneurs Network puts it:

“Visitors would see drone deliveries in action, take rides in driverless cars, actually use the latest in virtual reality technology, play with prototype augmented reality devices, and see organ tissue and metals and electronics being 3D-printed in front of them. They would see industrial manufacturing robots in action, have a taste of lab-grown meat at the food stalls, meet cloned animals brought back from extinction, and themselves perform feats of extraordinary strength wearing the exoskeletons that are already in use in factories and warehouses. Visitors would naturally get to meet the inventors and scientists and engineers who developed it all, too. They would browse the latest in fashion, art, and architecture, seeing them alongside historical examples. And the whole thing would be powered using only the cutting edge of clean energy technology, much like how the great new Corliss Engine drove the 1876 Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia, or how Westinghouse’s alternating current powered the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair. Visitors might also be able to view air CO2 removal machines in action.”

A modern Great Exhibition would be a magnet for international investors seeking opportunities in the UK's vibrant technology sector. By showcasing the country's commitment to innovation, the exhibition would demonstrate the potential for lucrative partnerships and investments. It would attract the attention of venture capitalists, industry leaders, and entrepreneurs, fostering economic growth and creating job opportunities. Additionally, by highlighting the UK's thriving research institutions and vibrant startup ecosystem, the exhibition could draw global talent, promoting knowledge transfer and enriching the nation's pool of skilled professionals.

A Great Exhibition would provide a unique platform for international collaboration, fostering partnerships between the UK and nations around the world. By inviting countries to showcase their technological advancements, the exhibition would encourage knowledge exchange, cross-cultural learning, and collaboration on global challenges. This shared experience could create lasting networks and partnerships, promoting diplomacy and cooperation across borders.

Hosting a Great Exhibition would generate a sense of national pride and confidence in the UK's capabilities. It would remind the world of the nation's rich history of technological progress and innovation, while also signaling a bold vision for the future. By celebrating its achievements, the UK can inspire a renewed sense of purpose and confidence in its ability to shape a prosperous and sustainable future.

There is no doubt that a modern Great Exhibition holds immense potential for the United Kingdom. By showcasing its commitment to new technology, the UK can stimulate innovation, attract investment and talent, foster international collaboration, and boost national pride. This exhibition would serve as a testament to the nation's determination to embrace progress, shaping a future where innovation and technological advancement drive economic growth and societal well-being. The time has come for the UK to once again captivate the world's attention by hosting a Great Exhibition that reaffirms its status as a global leader at the forefront of the technological frontier.

To be conspiratorial - who was giving Tanzania such terribly bad advice?

A little story from the world of metals. Indiana Resources has just won an arbitration case against the government of Tanzania. The full announcement is here. Pretty open and shut case in fact, effectively the government nicked a nickel mine and didn’t pay compensation for having done so.

But there was something of a pattern of this in Tanzania. The previous President, John Magufuli, had a habit of insisting that the mining companies were ripping the country off. Maya Forstater (yes, that lady, of beliefs in gender fame) describes the Acacia Mining case here. To convey the meaning without the reading the claim was entirely ridiculous. Either so grossly misinformed as to be delusional or entirely made up.

At which point who has been, or was at least, purveying such nonsense to Magufuli? We do suspect that it was some NGO or suchlike advisor but we’ve no idea who at all. Whoever it was has just cost Tanzanian taxpayers $100 million and change in the compo that now needs to be paid to Indiana Resources.

What we particularly relish is that it’s possible to take the story one layer deeper. Unconnected - entirely unconnected - with the Tanzania case there was the one about Zambian copper export revenues. This analysis was performed by Alex Cobham while at the Centre for Global Development. It was ludicrously wrong, something pointed out by Maya Forstater (with a very small assist from one of us here). Cobham then left CGD to go and run the Tax Justice Network (a step up for that organisation, previously it was Professor Richard Murphy). This meant space at CGD for a researcher which is where Ms Forstater landed - and yes, the same CGD that was the defending employer in the recent case about gender. Which we do think is cute.

However, back to the larger point. Someone, somewhere, has clearly been feeding gross misinformation to the Tanzanian government over mines and mineral deposits. That misinformation has - just so far, as this one case emerges from arbitration - cost Tanzanian taxpayers that $100 million and change. Don’t you think we should hunt down whoever caused this catastrophic loss and make them pay the bill?

Even if nothing else we do think that causing some sleepless nights for those who purvey entirely ghastly advice - so obviously wrong that Tanzania’s own appointment to the arbitration board ruled against them which is how we read the statement that the decision was unanimous - to poor country governments would be a good idea. Being wrong for good reason is forgivable, but if we can find who it was we can ask their reasons and find out whether they were good.

Or, to put this another way, those who’ve been misleading poor country governments over mineral claims and values should be made to sweat a little, no?

Adam Smith's Legacy

On this day in 1790, the great economist, moral philosopher and social psychologist Adam

Smith died. The story is that he was entertaining friends at his home, Panmure House off

Edinburgh’s Canongate, when he felt unwell, rose and said: “Friends, we will have to

continue this conversation in another place.” He died soon after.

It’s a nice story, though greatly exaggerated for effect. Adam Smith’s religious beliefs are a

matter of debate, and it unlikely he believed in an afterlife anyway. Indeed, though he died

seventy years before Darwin’s Origin of Species, he was grasping towards an evolutionary

explanation of why human life, in economics, morality and other areas, seems to serve us in

generally beneficial ways, without the need for any conscious direction from governments

or anyone else. As if directed by an Invisible Hand, he wrote, though he knew there was no

conscious entity moving that hand. Or Providence, he suggested. How it generated the

harmony that F A Hayek would later call spontaneous order was a mystery to Smith, and to

his friend David Hume and other scholars of the age.

Smith ordered that, on his death, all his papers should be burned, apart from one essay on

The History of Astronomy. It was not such an uncommon request at the time: people did not

want to be judged on the basis of their random notes and half-though-out jottings. But we

were lucky he spared The History of Astronomy, which is a remarkable essay in the

philosophy of science, advancing a trial-and-error thesis that would not be lost on the

twentieth-century author of The Logic of Scientific Discovery, Sir Karl Popper.

The fact that Smith wrote on scientific method demonstrates how wide his interests

and his expertise were. As well as the economics for which he is most remembered today, he also

wrote and lectured on the use of language, on the arts, on justice, on politics and on moral

philosophy. In fact it was his first book on ethics, The Theory of Moral Sentiments, that in

1759 made him internationally famous — and guaranteed him a generous income for life

that would give him the freedom to think about economics and write his 1776 masterpiece

An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, which he referred to as his

Inquiry, but to us is known as simply The Wealth of Nations.

In this, Smith offers an explanation of why, in economics, the spontaneous order idea

works. For centuries, people imagined that the only gainers in any economic transaction

were those who ended up with the money. But Smith noted that their customers benefited

too, by getting goods or services that they valued more than the cash. Indeed, the trade

would not happen unless both sides thought they were getting value from it. To maximise

the creation and distribution of value, he concluded, we need to be facilitating free

exchange — not thwarting it with protectionist measures against foreign imports or

domestic regulations on what and how people are allowed to trade.

This simple ‘system of natural liberty’, explained Smith, was what allowed the spontaneous

society to flourish and raised nations from poverty to prosperity. It enabled individuals to

strive to ‘better their condition’, and that of their families. By contrast, regulations and laws

were too often laid down by politicians and their business cronies: to promote their own

interests, most generally in opposition to the interests of the working poor.

Smith would have regarded a government that controls nearly half the economy, spending

nearly half the nation’s GDP — a concept that he introduced to the world on the very first

page of The Wealth of Nations — as the greatest tyranny. Taxes, he thought, were another

way in which established interests skew things in their favour and block potential

competition. Taxes, he argued, should be as low as possible, should encourage rather than

restrict free trade and innovation, and should be simple, understandable and convenient to

pay. One can imagine what he might have thought of a tax code like the UK’s, which is

longer than The Wealth of Nations itself, and a regulatory rule book that is even longer.

When economic freedom, tempered by Smith’s moral virtues of prudence, justice,

beneficence and self-control, has been allowed to flourish, it has led to the greatest

increase, and spread, of human prosperity. The free trade era of the nineteenth century

enriched much of the world and brought humanity cheap food and manufactures. The

globalisation of the twentieth and twenty-first brought nearly all nations into the world

trading system and thereby pulled a billion people out of dollar-a-day poverty.

Adam Smith’s intellectual and practical legacy is plain enough. The issue is whether the

world’s governments will ever stop frittering it away.

Cheap, clean energy is on the way

Eight years ago in 2015, I published “Britain and the World in 2050,” setting out my predictions for the world ahead of us. It was widely covered in the media, with journalists going to town on the recreated woolly mammoths and dinosaurs, not revived from mosquitos preserved in amber, but by back breeding and genetic manipulation of flightless birds.

Some also picked up and covered my remarkable prediction that the cost of energy would have dropped dramatically by 2050. I wrote:

“Energy costs will by 2050 be a fraction of their present-day costs. For most consumer uses, energy will be effectively free.”

The cost of energy has witnessed several spikes since then, and is now more expensive than it was. Partly this is down to the Russian invasion of Ukraine, with some contribution made by a go-green agenda that shuns the cheaper sources in favour of more expensive ones.

Nonetheless, I remain convinced that my prediction will come about. The fossil fuel we’ll still be using will be gas, but nuclear will take a larger share, particularly with the new small reactors coming on line. Solar will be making a major contribution, as ways are found to increase the efficiency of photo-voltaic cells by combining ultra-thin surfaces on the silicon.

There are several new technologies that could be game changers. There are vast reserves of natural hydrogen beneath the Earth’s surface, more than previously supposed, and more accessible.

The US Geological Survey concluded in April that there is probably enough accessible hydrogen in the earth’s subsurface to meet total global demand for “hundreds of years”. Currently, the effort to extract it commercially resembles the early days of fracking, with ‘wildcatters’ setting the pace. It portends cheap and clean generation of electricity, bypassing fossil fuels and emitting no greenhouse gases.

Another possible technology involves the use of thin layers of materials flecked with nanoholes. The pores are essentially small enough (100nm) that the molecule's electrical charge can pass through them and be harvested to generate electricity. Water molecules pass through, generating a charge imbalance that produces harvestable electricity plucked not from thin air, but from naturally moist air.

The device is called an Air-gen and can operate at all times despite the weather conditions because moisture is always in the air. When scaled up, it offers low-cost, clean electricity.

A newer technology from scientists at the University of Rochester uses semiconductor nanocrystals for light absorbers and catalysts and bacteria to donate electrons to the system. The system is submerged in water and driven by light. Bacteria interact with nanoparticle catalysts to make hydrogen gas more cheaply than can be achieved by electrolysis.

It is not that any of these might necessarily be the magic bullet that gives us cheap, clean energy. It is that some of them, in combination with yet more ingenious ways still to be developed, will give us the energy we need at a price we will be prepared to pay. And that price will be very low. We won’t use less energy; we’ll just produce it more cleverly.