Lab Grown Meats: A New Solution?

Lab-grown meats are not yet widely considered to be the new solution to the soaring food prices. However, the introduction of this greener and higher tech way to soften the predicted 70% hike in meat consumption by 2050, could be found in cell-cultivated meat production furthering the future of farming. Whilst some consider this innovation to have a Pandora’s Box effect, initiating discussions as to whether such lab-grown meat will be compatible with vegetarians or even Halal meat, the positives for alternative meat provision cannot be underestimated.

It is hard to ignore that, as millions globally move away from subsistence farming, and as there has been an increase in the Westernisation of dietary culture in the face of globalisation, meat consumption in the world population has drastically shifted. Between the years 1964 and 1966, average meat consumption per person per kg in East Asia was 8.7kg. From 1997 to 1999, that value increased to 37.7kg, increasing over 330%. Evidentially, cultivated meats provide a solution to satiate demand without having a toll on the planet, revolutionising the industry physically and economically.

Equally, it is possible to see that the favourable mechanism by which tissue cultures are extracted from the embryonic chicken heart provides the culture with significant nutrients; a technology which could be expanded to increase the lifelikeness of meat production given the appropriate investment, presenting a myriad of opportunities.

One such benefit that cultured meats have is removal of adverse amounts of waste which is becoming increasingly desirable. For example, the fact that we only eat the wings and breast of a chicken is blatantly wasteful, with 16.8 billion remaining chicken carcusses being wasted annually. The ASI’s local Butcher suggests that almost 1⁄3 of every chicken bought is discarded, amounting to almost 4 - 6 kg daily from a singular butcher, illustrating the fundamental wastefulness of the current meat industry.

The benefits that are attached to the modernisation of the agriculture industry cannot be underestimated, with farming fewer animals having the potential to reduce greenhouse gas emissions of gases such as methane and carbon dioxide by almost 78%-96%. Revolutionising one of the most environmentally harmful industries which inefficiently yields products can only be a positive. Cultured meats and their production within sterile labs require 99% less space than the traditional animal husbandry market, potentially saving 17.5 million hectares of the 17.6 million currently used for pastoral land. Such new land could be used for the much-needed housing developments in the UK or alternatively the reforestation of the British countryside is possible. The reduction in monoculture and the polluting disposal of pesticides would further protect the countryside and alleviate environmental concerns.

Equally, animal rights concerns would be relieved at the benefits that this would have on the movement of live animals and the unethical production of meat illustrated by battery hens, satisfying a consumer preference whilst maintaining food production. The important sterile environment would also reduce zoonotic diseases, preventing outbreaks such as the Avian Influenza epidemic of 2021 reducing the number of livestock for consumption. Additionally, lab-grown meat has the potential to protect endangered animals, with the production of synthetic exotic meats devaluing poachers' keep and undermining the black market.

Perhaps most importantly, the greater affordability for the general populace remains significant but equally such modernisation would create the opportunity for ‘fashionable expensive meats’ to be bought up by the rich, satisfying all. Equally, the production of cultured meat and its acceptance into the food industry would predicate great food safety, enabling cultures to be taken from good quality meat and maintain sufficient regulation, as is currently being experienced by the FSA.

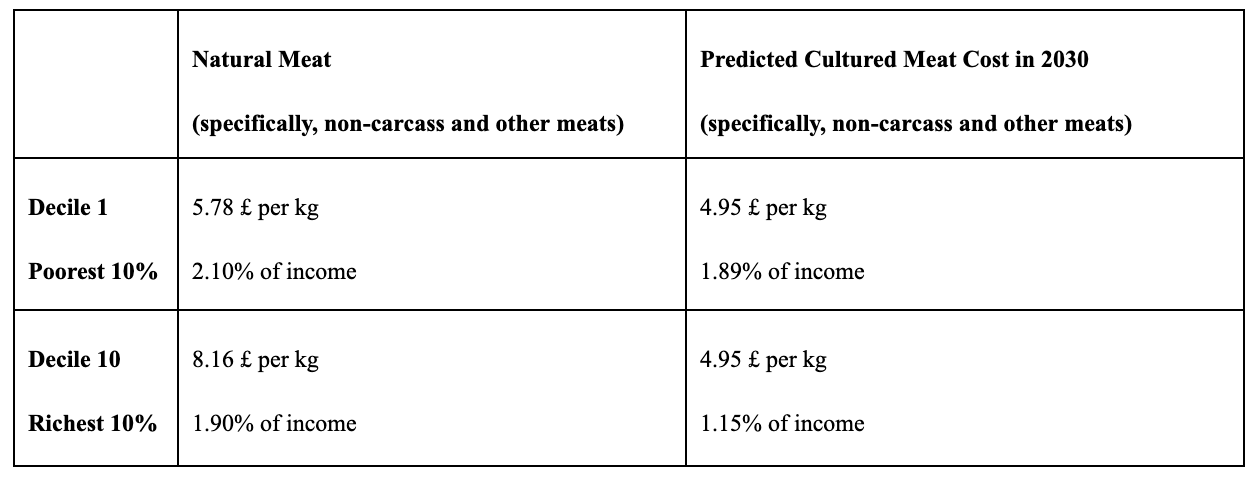

The problem currently is the price tag attached to the investment in lab grown meat production, however, with sufficient investment, prices could be a fraction of natural meat, aided by the removal of laborious red tape. Unnecessary over-protective regulations are the outcome of special-interest lobbying by large interest groups put up by Food Standard Authorities generating inefficiency in culinary advancement, as government officials wish to stick to the status quo and limit the potential for outside scrutiny.

Whilst funding for such innovative food production remains limited, with only a few large scale productions such as Mosa Meats’ televised hamburger event, where a €250,000, squashing its pioneering potential; the UK has proven to be on the frontline of domestic production, while only on a small scale. The UK-based pet-food company, Meatly, will begin selling its cultivated chicken to manufacturers as early as this year, setting the UK to become one of the first countries in Europe to commercialise ‘lab-grown’ meat, as a positive movement.

You can read Dr Madsen Pirie and Jamie Hollywood’s longer report here.

Pollynomics never does work, but really Ms. Toynbee this is absurd

The first rule of economics is “Incentives Matter”. At which point:

On the contrary, finding money for productive capital investment in Labour’s priorities for growth, green energy and a housebuilding bonanza

It’s possible to mutter about whether that’s the right goal and all that but let us accept it as the one being pursued. After all, economics doesn’t tell us what the goal should be it just explores ways of getting there.

The frontrunner is raising capital gains tax (CGT)….Why, the IFS’s Paul Johnson asks in his book Follow the Money, is capital gains tax not due on a lifetime of shares, property or antiques, swollen in value but absolved on death?….inheritance tax (IHT) paid by just the wealthiest 4% of estates and too easily avoided: why do pension pots, farms and family businesses escape it?….It’s time to charge national insurance (NI) on all income, not just on pay,….Pensions tax relief is ripe for reform: high earners get 40% and 45% relief subsidised by the state…. Just as a thought experiment, the LSE’s wealth commission shows a one-off raid on wealth above £2m, charged at 1% a year for five years, would bring in £80bn.

Excess wealth and income is there for the plucking

So, if you invest well - profitably, that proof that the investment was a societally useful one - then we’re going to double the share of that profit confiscated. If you don’t bother to sell but keep it for your kids then we’ll take 80% of it (IHT plus CGT). We’ll raise the tax on income from investments by 15 percentage points. Don’t even think about saving for your old age of course - pensions pots being by far the largest source of capital. And if you manage to avoid all of those strictures then we’ll come take your money anyway.

As we say, economics doesn’t tell us what the goal should be, only possible pathways to arriving at the intended destination. Or, of course, pathways that won’t get us there.

So Pollynomics is telling us that the way to increasing productive capital investment is to nick all the money anyone might ever achieve from making a productive capital investment?

This violates that first rule of economics, that incentives matter. But then, you know, Pollynomics, it’s never been any better than this.

Tim Worstall

Nothing makes sense about working hours without household labour

Emma Beddington is merely the latest to miss the damn point here:

I studied economics for a brief, inglorious time 30 years ago – with about as much understanding as a pigeon, actually – but the one bit that stuck was John Maynard Keynes’s assertion that, in future, we would work 15-hour weeks.

So, why hasn’t it happened then? Which is to miss the point that it has happened.

Absolutely nothing will make sense about working hours unless we include household - and unpaid - hours in our calculations. Yes, we leave the house to go work for The Man. No doubt being expropriated of the value of our labour and so on. We also work inside the house without The Man. Childcare, cooking, cleaning, fixing the gutters, digging the veggies, go back a little further and spinning the yarn, weaving the cloth and strangling the pig.

The actual change in working hours in the (near) century since Keynes wrote is that male market working hours have fallen, female market working hours risen. And male household hours have fallen and female household have fallen off a cliff. One estimate we’ve seen is that the weekly labour hours required to run a household have fallen from 60 in about that 1930 to 15 today. The nett effect is that all have very much more leisure than back then.

We have another name for this, it’s the economic liberation of women. Exactly the thing which has allowed women to come out of the kitchen and take their place in government, business, the media and even the military. We think it’s absolutely great too.

The 15 hour week has already happened. It’s just that it happened in that household labour sector, not the market one.

And, well, it just shouldn’t be that difficult to work this out. The Keynes essay does talk about the charwoman, no?

As we have done before we suggest a little test. Talk to some doctors (obviously not professionally, as they don’t see patients any more) and ask how many cases of housemaids’ knee get treated these days? Many more cases of tennis elbow we’re sure, but a vanishingly small number of housemaids’ knee. Well, there we are then.

Tim Worstall

A new bank in town: the approval of Revolut’s banking licence

On the 24th July, the global fintech company, with over nine million UK customers, officially received its UK banking licence, years after it first applied. Whilst Revolut securing a licence is a positive step towards the liberalisation of banking and giving the average person greater freedom of choice, this begs the question as to why this has taken so long.

The news about Revolut’s banking licence approval has been met with great support for diversifying the current banking market, however, the addition of a singular bank falls short of neighbouring countries, such as Germany. The German economy benefits from the thousands of licensed banks compared to the five banks that make up Britain's banking and financial services, making the UK’s banking network one of the most homogeneous in the world. The small number of banks available to the general public has somewhat monopolised the arena for which the average consumer in the UK has very limited choice. In fact, the five leading banks—Lloyds Banking Group, RBS, HSBC, Barclays, and Santander—have an 85% share of the personal current account market, illustrating the limitations for the consumer.

Revolut, who has 45 million worldwide customers, already had licences in Lithuania and Mexico. It now hopes that the UK’s approval will help it to expand its activities in key markets like the US and Australia. It had filed a licence application back in early 2021 but had faced substantial setbacks. The reasons stated included trouble with revenue verification, following delays to the 2021 and 2022 accounts being released, as well as the departure of senior executives and the ownership structure. The entry of Francesca Carlesi, former Deutsche Bank executive, into the company’s leadership back in November has helped subdue the technocrats at the Prudential Regulation Authority (PRA). While there is the argument to be made that filing an earlier application, when the company had been much smaller, which may have helped it secure its licence faster, the argument fails to remove the fault resting on the overly stiffened bureaucracy taking so long to approve one of the most trusted Electronic Money Institutions in the UK.

The company differs from more traditional banks in its focus on primarily online banking - a move which has drawn customers through its accessibility and ease of entry. It is in talks to sell $500mn worth of shares in the hopes of boosting its market valuation from $33bn (as valued in 2021) to $45bn - a move which, if successful, might make it a contender for third place among UK banks, replacing Barclays and being only surpassed by HSBC and Lloyds Banking Group. However, there are growing concerns that the current macroeconomic environment, with a drop in interest rates expected soon, might reduce Revolut’s profits. Considering the fact that interest income had accounted for over a quarter of the company’s revenues last year, this may pose worries.

The three year wait for Revolut’s licence exemplifies the red tape delays in the British banking market produces and, despite the longevity of the wait, the licence provided comes with significant restrictions, meaning that new products from Revolut will be unable to be launched, further limiting the choice of individuals. The Bank of England’s suggestion for the movement into the mobilisation stage, provisioning a conditional phase allowing for finalisation of the IT infrastructure, governance, and risk management frameworks. Revolut must attempt to secure further investments but in the meantime this phase allows greater protection of the Financial Service Compensation Scheme (FSCS) for customers. It must be noted, that the provision of the mobilisation phase does not allow for the complete success of the liberalisation of the financial sector, rather further illustrates the struggle that innovative banks face in licensing agreements.

Whilst Revolut’s licensing has the potential to benefit UK customers, protecting their money, the need for greater removal of red tape around regulation on businesses is essential to economic growth, with the overcomplicated nature of the regulation strangling businesses and growth in markets. The need to reassess British financial markets is becoming ever more obvious and therefore necessary to boost the economy through greater competition between a multitude of banks and attract greater investment, something which the government’s slow pace of reform is limiting.

Getting wealth entirely wrong

So a report to come from the Resolution Foundation and, given the source, one that’s going to entirely miss the actual point about wealth:

Rachel Reeves could quickly find around £10bn a year to plug half of the fiscal hole left by the Conservatives if she were to raise taxes on soaring levels of unearned wealth, according to leading economists.

Tax as a portion of GDP is already the highest since WWII. The problem is therefore how much and what it is being spent upon, not the collection of revenue. So, there’s one bit of guidance on closing the black hole - spend less.

But the mistake goes further:

The report finds that levels of wealth have risen from four times the national income when Labour was last in power to six times the national income today, despite the recent rise in interest rates.

Even a brief familiarity with the numbers will show us what’s wrong with this insistence. For of course the implication is that there’s some group of Moneybags out there sitting on all that wealth a la Scrooge McDuck. Which isn’t, at all, a useful picture of wealth in Britain.

“Financial assets” is that portion of the population’s wealth which is - potentially at least - owned and sat upon by pince nezed waterfowl. This hasn’t changed much in even nominal terms, let alone real or as a portion of the economy. The two - by far - largest portions of wealth are house prices and pensions funds.

House prices we want to reduce anyway and we’ll do so soon enough once we blow up - kablooie - the planning system. Pensions, well, has anyone noted that we’re an ageing population? That we all now live 15 and 20 years into retirement rather than 3? Therefore we all save more into our pensions as we’ve a couple of decades to finance with them. We even have long and agonising conversations about how to encourage more of this desirable behaviour.

Overall, the Resolution Foundation study finds that wealth inequality is nearly twice as high as income inequality. It notes that on the eve of the pandemic, three in 10 families had less than £1,000 in savings – meaning they lacked any real safety net.

Wealth inequality always is higher than income, that’s just the way things work. And it’s wildly wrong to say that people lack a safety net in a country with a welfare system. What does anyone think we have the welfare state for if it’s not to provide a safety net? Meaning that folk don’t have to have direct savings because the welfare state already does that.

Finally, if pensions are a vast portion of wealth - they are - and we’ve an ageing population - we have - then we’ve got to take lifecycle effects into account when surveying that wealth. For, clearly and obviously, household wealth will peak just before, at and just after retirement date. Which no one does bother to do. That “top 10%” has a very definite age profile to it that is.

The reality here is that the establishment has managed to spend all and more of what can be squeezed out of the population’s incomes and consumption. Therefore there’s a desperate casting around for a - any - other form of taxation that can be imposed and damn logic or even analysis while doing so. The correct answer of spending less of everyone elses’ money isn’t discussed. For who does go into politics other than to spend everyone elses’ money?

Tim Worstall

Time for the Competition and Markets Authority to go perhaps

If you charge a lower price than the other guy then you’re driving them bankrupt - unfair competition. If you charge a higher price then you’re gouging the consumer. And if you charge the same price then of course you’re colluding. This means that any bureaucracy looking at pricing in the economy always has a way to hang you:

Petrol stations have been branded “outrageous” after overcharging motorists by £1.6bn last year.

The Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) found that petrol stations’ fuel margins – the difference between what a retailer pays for its fuel and what price it sells it at – remain significantly above pre-pandemic levels.

The regulator said the price mark-up was particularly stark at supermarkets, whose fuel margins are roughly double what they were in 2019.

Erm, OK. But what was happening in 2019?

Motorists should not expect to see a return of supermarkets using cheap fuel to lure in shoppers, an industry source has told Sky News.

Oh:

Cast your mind back to the bad old days before the pandemic when the supermarkets were always trumpeting their latest cuts in the price of petrol, and thousands of independents hated them for it. The supermarkets claimed their financial muscle meant their costs were lower than the rest of the market – which was true – and they were simply passing on the benefit to their customers. But everyone knew they were also taking a minimal margin in an attempt to draw shoppers into their stores.

Gosh:

Supermarkets have the incentive to sell cheap petrol as a loss leader. Independent retailers make all their profit from petrol (except selling food in small shops). However, supermarkets have an incentive to offer cheap petrol to encourage people to go to Tesco or Sainsbury’s. People often do both petrol buying and a big supermarket shop. Therefore, even if the profit margin on petrol is very low, it doesn’t matter because they will make a profit from selling more groceries. This has been another factor in lowering prices.

Supermarkets and other fuel retailers will soon have to publish live fuel prices. Will food be next? Be honest and get ahead of the transparency curve. Major food retailers should show real leadership by ditching loss leaders.

For car owners, such price cutting seems heaven-sent. For the major oil companies, it is a gamble forced upon them by the supermarkets. Esso and Shell are having to take such drastic measures to arrest the decline in their market share as millions of customers switch to supermarket pumps.

Superstores such as Tesco, Sainsbury’s and Safeway are effectively operating as oil companies, buying cheap petrol supplies in huge volume on the open market, and retailing through their on-site filling stations.

So, before pandemic lockdowns and so on the supermarkets were selling petrol at low or no margins as loss leaders. The CMA observed and thought this was bad. Petrol retailers have to provide their pricing now in a transparent manner and this has - given the crackdown on loss leaders - led to prices and margins rising. The CMA observes this and thinks that it’s bad. The supermarkets are ripping off consumers by not selling petrol as a loss leader, instead charging a more normal margin.

The CMA is complaining about the effects of its last complaint. This is the sort of self-regarding behaviour that will turn even a bureaucracy blind.

The thing is we’ll never change the behaviour of a price monitoring bureaucracy. They will always do this - it’s either too aggressive, gouging or collusion. It’s never, ever, market participants simply competing. As we’ll never change the behaviour of the bureaucracy better to do without the bureaucracy. And the taxpayer thereby saves the cost of it which they could apply, as they wish or not, to petrol.

Tim Worstall

Elinor Ostrom did not solve the Tragedy of the Commons

Elinor Ostrom did gain her Nobel for asking that very interesting question - if the Tragedy of the Commons is inevitable then how come we have commons that have survived? In the absence of Hardin’s only two solutions, capitalist ownership or socialist regulation that is?

The answer being that sometimes - time and place dependent - social pressure and mutual agreement can do the job.

Every Thursday at noon, outside the west door of Valencia’s cathedral, nine black-cloaked figures – one wearing a banded cap and with a ceremonial harpoon by their side – gather for their weekly meeting, as they have done for hundreds of years. This is the Tribunal de les Aigües (Tribunal of Waters) – a water court that may be the oldest institution of justice in Europe.

….

The tribunal was of special interest to Elinor Ostrom, winner of the Nobel prize for economics in 2009, who considered it an ideal example of “the commons”, where communities around the world have devised rules for sustainably sharing and managing their scarce resources, from waterways to fisheries to forests. It is a direct counter to the mistaken idea of the “tragedy of the commons”: the belief that, left to our own devices, self-interest will necessarily drive us towards overusing shared resources. Examples like Valencia, as well as the water boards (waterschappen) in the Netherlands that manage canals and Bali’s subak system that has functioned to share water among rice farmers for the last millennium, reveal this to be a myth.

Ostrom’s question - the difficult part always being asking the interesting question - shows that this answer will work. Sometimes. 11 old farmers sitting outside a cathedral will work on a small and tightly knit community of farmers. Who’s cleared their section of irrigation canal, who is taking more than their fair share of water etc. But, time and place dependent:

Valencia’s water court may even hold lessons for the parched countries of the Middle East. More than a decade ago, leading Palestinian hydrologist Abdelrahman Al Tamimi suggested they should “import and adapt the model of the Tribunal of Waters … not only to resolve conflicts between farmers, but to reduce tensions between Israelis, Palestinians and Jordanians”. Without such mechanisms, he believed, there was little chance of developing the grassroots trust and dialogue to manage water scarcity effectively. “We can fight for water or cooperate for it – it depends on us,” said Tamimi. “The first step is to trust each other.” The current conflict has only heightened the need for long-term water collaboration.

The entire Jordan watershed is not, quite famously, the sort of tight knit community which can be ruled and judged by 11 old farmers. The social pressure simply isn’t there. Thus we are back to Hardin’s two possible solutions.

The very absence of the necessary community tells us that the community solution will not work. QED.

Of course, it’s possible to wonder why anyone bothers reading social science research if they’re not willing to understand the answers given in social science research.

Tim Worstall

To point out that this is a very, very, silly idea

Of course, given that it’s Robert Reich talking about economics and taxation is proof enough of that headline. But we’ve heard little whispers that some would like to think of doing this in Britain too. It’s an extremely silly idea:

If a wealth tax is not politically feasible, an alternative would be to end the “stepped-up basis” inherent tax rule that allows heirs to great fortunes to avoid paying a dime of capital gains taxes.

The step up rule is not about absolving people of capital gains taxes. It’s to make them subject to inheritance taxes.

To take a slightly stylised real world example. Jeff Bezos is, dependent upon the day and the hour, worth some $200 billion. Assume that’s all Amazon shares - it isn’t but just assume for a moment. We forget the actual number but upon incorporation of Amazon Bezos paid some $5,000 or $10,000 for his shares as his part of capitalising the company.

We can say whatever we like about the glory of capitalism in the returns available to those who enrich the rest of us or, obviously, as some do the rapine of the body economic by such concentrations of wealth.

But the step up basis. At the point of the death of Mr Bezos - long may he prosper, long in the future may that unhappy day be etc - what is the value of those Amazon shares? $5,000, the original purchase price? Or $200 billion, the current market value?

The step up basis is that death of the owner crystalises valuations to current market value. Values are stepped up from purchase to market value as the basis of evaluating the estate for inheritance tax.

Whether there should be inheritance tax or not is another matter. What the rate of such a tax should be equally so. But if there’s going to be an inheritance tax we’ve got to agree upon how we value what for the purpose of said tax. The step up basis is exactly that, market value at time of death.

Eliminating the step up means that the Bezos estate gets charged the estate tax on the $5,000. This is not a logically sound basis for such a tax.

That the inheritors don’t get charged capital gains tax upon what they inherit is a logical consequence of this. They’ve just paid 40% so the value at death is the starting point for any future tax liability.

It is, of course, possible to change this system. Perhaps no inheritance tax but CGT on assets inherited. Or the current IHT and no CGT.

Reich - and others who purport to support the abolition of the step up basis - never do seem to grasp that the point is to enable the taxation of the estate. And doing both - CGT and IHT - would have nominal rates at up around 80, 85% (they call for capital gains and income taxation to be equalised as well, so 40 to 45% plus the estate taxation of 40%) which isn’t a system that’s going to work.

”Those b’astards never pay CGT because muh step up basis” is good political rabble rousing but lousy, ignorant commentary upon either tax or economics. But, you know, Professor Reich……..

Tim Worstall

Whatever the pension taxation changes they must apply to everyone - yes, everyone

There’s much chatter about how the taxation of pensions contributions is going to changed and so on.

Rachel Reeves will be urged to raid the pension savings of up to 6m middle-class workers in plans presented by Treasury officials ahead of her first Budget.

The Chancellor is expected to consider a proposal for a flat 30pc rate of pension tax relief – meaning that higher rate payers will pay an effective 10pc tax charge on their retirement contributions for the first time.

The plan would affect up to 6m higher and additional rate taxpayers, costing the wealthiest savers around £2,600.

Well, maybe, etc. We’d remind that it’s not actually pension tax relief it’s pension tax deferral. The pensions are taxed as income on their way out of the pot in those future golden years. So taxing money that goes in and also that that comes out is pretty obviously double taxation.

However, our real insistence here would be that whatever the rules then they’ve got to apply to everyone, equally. To civil service pensions for example. To NHS doctors’ pensions - to MPs’ pensions, obviously. And do so at reasonable calculations of the pension valuation too. None of this use of varying discount rates to prove that, acshully, that £80k a year civil service pension is only worth 2 pence as a capital sum. Similarly, if teacher pensions’ employer contributions are equivalent to 23% of salary (a figure we’ve seen somewhere or other) then that 23% gets taxed just like any other pension contribution. So too those of the higher levels of the civil service - obviously.

By analogy think of the rule of law. The definition of which is that it applies to all equally. Even Cabinet Ministers (even if ex-) can get 7 years’ pokey for lying about a hotel bill. The Permanent Secretary gets his pension and his pension contributions taxed in exactly the same way as the hotel receptionist.

Quite apart from anything else we tend to think this will improvethe advice Ministers receive on the subject.

Tim Worstall

And so they prove that The Spirit Level is a crock

The originators of The Spirit Level, Wilkinson and Pickett, take to The Guardian to reveal that they were right all along:

Our landmark book revealed the cost of inequality. Fifteen years later, things have only got worse

Richard Wilkinson and Kate Pickett

We have long thought that the claim was something of a crock. Imagine our joy at the crockness being proven by Wilkinson and Pickett.

When economic inequality gets worse, so does our health and wellbeing. Inequality can affect a society’s death rates, its levels of chronic disease, and the amount of violence (including murders) it experiences. What we weren’t prepared for when we first wrote the book was how much worse things could get.

That’s the theory. The hypothesis if we are to be more accurate about it.

And our data show that even small differences in inequality matter: marginally reducing inequality can have a big impact on people’s health and wellbeing.

That’s a prediction derived from the hypothesis. Which is excellent, it’s now possible to do science. We see whether the prediction accords with reality as a test of the hypothesis. Remember, it only needs one of those ugly facts to disprove an hypothesis.

Things have got worse - that claim from the first quote. If inequality reduces from what it was in those dying days - 2009/10 - of the Brown Terror then things should get better. So, what has happened to inequality in that time period?

The Gini, the usual measure of inequality in a society, has declined from 36.6 (all individuals) in that origin year to 35.7 (2022, last year currently calculated).

We’ve had that marginal decline in inequality and yet things are still getting worse. The hypothesis is a crock, isn’t it?

Sure, sure, we all knew that anyway but it’s nice to have the proof from the horses’ mouth. No?

Tim Worstall