We support road pricing but things will be different

We have long, long, supported road pricing here. But it’s still true that it’s going to change things in ways some won’t like:

Rachel Reeves has been urged to consider a radical driving tax on electric vehicles (EVs) as a £9bn black hole looms from the loss of fuel duty.

PwC has suggested taxing EVs based on how far they drive to prevent the decline in petrol and diesel cars on the road blowing a hole in public finances.

The Government risks losing out on £9bn of fuel tax revenues by 2030, according to forecasts from PwC, when one in four vehicles on the road is expected to be electric. EVs do not incur fuel duty since they are fuelled by electricity.

Logically, the taxation of the two types of car - ICE and EV - should be different. ICEs do have that issuance of CO2 to deal with. But both also contribute to congestion, both require money to be spent on roads, A&E and so on. The taxation should reflect those differences. ICEs and EVs should be charged the same tax where they are the same (and we can get into EVs are heavier, more tyre wear, greater damage to roads etc if we like) and different taxes where they are different.

So, road pricing, yes. Great. The same for each type of vehicle.

But what should the CO2 tax be? Usefully, the Stern Review tells us this - 12 p per litre of fuel used. Which means that when we move to road pricing the fuel duty should fall to that 12 p per litre of fuel.

Excellent, we’ve now a logical taxation system for cars. The world is properly balanced for the costs transport imposes upon others.

There is though that one little difficulty. We’re not sure of this but we suspect it might well be true - ICEs will now be cheaper than EVs in their overall costs to drive. And the thing about logical systems is that if that’s the outcome then that’s the outcome.

If EVs, including all relevant costs, are more expensive than ICEs, including all their relevant costs, then that’s just what reality is telling us. ICEs are cheaper than EVs. Shrug.

Tim Worstall

The grift never stops, does it?

Brazil led the way. Now the UK should get behind the assault on hunger and poverty

Kevin Watkins

At its recent summit, Lula gave the G20 a chance to show its commitment to real change – and Britain can take the lead

The argument is that the rich countries should send much more money to the poor countries. Because we’d like to beat that hunger and poverty.

Indeed, we would like to beat that hunger and poverty. At which point, well, what’s the best method of beating hunger and poverty? The answer to that is obvious - economic growth. Even if we do say that past a certain point economic growth doesn’t make us all happier - not that the Easterlin Paradox is actually correct - it’s still wholly true that economic growth in poor places makes those poor places less poor and also happier and less hungry.

Good, so how do we do that? The answer is that other than the one very simple action we don’t. They do.

This past four decades of neoliberalism has seen the largest fall in human poverty in the whole history of our species. To the point that there were those Millennium, Development Goals, one of which was to make a serious dent in such poverty. The only one of the MDGs that was overachieved and early. None of it by rich countries doing very much other than agreeing to buy what looked good among the production of those poor places. What really happened is that the governments of the poor places stopped doing the stupid things that hampered economic growth. You know, followed the Washington Consensus of the ten stupid things not to do to an economy?

Poverty, these days, is caused by bad government. Bad government in those places that are poor.

So, what can we do about it? The most obvious is declare unilateral free trade. Anyone poor out there who makes something we might like then we’ll buy it without imposing ludicrous taxes or regulations upon ourselves for having done so. Other than reigniting colonialism to improve governance out there this is really the only useful thing we can do.

But what actually is the Brazilian demand?

Current aid for hunger and poverty – about $75bn annually – is not just falling for low-income countries, it is fragmented and delivered through mechanisms that weaken national ownership: only about 8% goes through national budgets.

They’re demanding that more money be fed through what is provably - poverty is caused by bad government recall - bad government. This is not a useful solution. It’s a grift.

We really do know how to beat poverty. Buy things made by poor people in poor places. Sending more cash to buy a second Rolex for the bureaucrats doesn’t do it. So, let’s do what works, not what doesn’t.

Trade not aid……hey, it worked last time.

Tim Worstall

A useful guide to why British housing is so appalling

Just consider the point being made here. Savour the flavour of it:

Tory areas given six times bigger increase in housing targets than Labour regions

Almost half of the Cabinet – nine out of the 22 members who represent seats in England – have had their building goals reduced

It’s possible to take issue with the plans themselves of course, targets have been raised in the North, where fewer people wish to live, and lowered in the SE, where more people do. Well done planners, eh? But savour. The new housing is to be dumped on the areas of those just out of power and the areas of those just in power are to be unblessed by more housing:

Tory councils have seen their house building targets increase by six times more than Labour ones, analysis by The Telegraph reveals.

On Tuesday Angela Rayner unveiled sweeping reforms to planning rules, including mandatory housing targets imposed on councils and a new algorithm to calculate them.

Analysis shows that, as a result, across the 55 Tory-controlled English councils which have planning powers, targets have been increased by 43.3 per cent.

Yet across the 121 council areas run by Labour, many of which are in the biggest cities, the upward revision has been just 7.2 per cent.

The political claim is that housing is a bad thing to be foisted upon enemies. That’s why that new housing - to be delivered by central planning - is being foisted upon the areas of enemies.

Which is that very good indeed explanation of why British housing is so terrible. Cramped, our new builds are the smallest in Europe, no one at all is prepared to allow anyone to build houses in Britain that Britons would like to live in where Britons would like to live. Why? Because the entire political establishment - both those doing this foisting and those complaining about being foisted upon - believe that housing is a bad thing. Clearly and obviously they do by their actions and complaints.

Houses are Bad, M’Kay?

What other explanation do we need for why British housing is bad?

Tim Worstall

National Debt is Rising By £381 Million Every Day

The TPA’s debt clock launched with a bang this week. And it’s hardly a surprise. For the first time in a while, the country, its politicians and its press have been talking about the state of the public finances. Not since the Cameron government has this really been the case. Ever since then our politicians have been guilty of reaching for the magic money tree every time a problem arose. Whether it’s paying for 18 months of aggressive lockdowns, subsidising the nation’s energy costs, pumping money into foreign wars or simply doling out cash everytime a campaign group or backbench MP got a front page of a national newspaper or a question at PMQs, it’s clear that there has been an attitude that the era of cheap money was never going to end. Or at least that they believed they would be long out of power when it did.

Often the government does need to spend money - supporting Ukraine is a noble endeavour that clearly is in our national interest, for example. But assuming the well is bottomless every time that a problem arises has to be made has led to the national debt now sitting at well over £2.5 trillion, ticking up by £4,410 per second, £16 million per hour, and £381 million per day. It’s equal to about £90,000 per household, £68,000 per taxpayer and £37,000 per person.

Of course the national debt has sat in the trillions for many years now, with most choosing to ignore it. Chancellors like to talk about debt falling as a percentage of GDP within a five year forecast period, but as Kate Andrews has pointed out, this is simply a recipe to fudge the figures and put off difficult decisions.

But it’s particularly relevant now for two, closely linked reasons. One is political. Reeves is desperate to get revenge for the devastatingly effective framing that the Conservatives deployed from 2010-onwards about the state of the economy. The difference is that she doesn’t have the open goal handed to Cameron and co in the shape of a letter saying, verbatim, “there is no money left.” Of course it’s more than just revenge. By convincing the country that her predecessors trashed the economy, she’s hoping to reap the rewards of any economic upturn and give herself breathing space for difficult economic decisions.

Which is exactly the point, and brings us to the second reason. She does need to make difficult decisions, extraordinarily difficult decisions. The £20 billion black hole she has identified is in significant part the consequence of spending decisions she has made. And there is no shortage of spending decisions she’s made, from the wealth fund, to GB energy and inflation-busting pay rises for public sector workers. But previously, governments had short term wiggle room on borrowing, more recently due to near-zero interest rates and further back because the deficit was much smaller and the debt much lower.

No longer. Whereas we were spending in the low tens of billions on debt interest for much of the last decade (still a problem, but a much smaller one), debt interest payments are now running at over £100 billion per year and are forecast to remain around that level for some years to come. That is catastrophic. If debt interest was a government department, it would be the fifth biggest. But in return we don’t get a welfare system, a police force or a navy. We don’t even pay down the national debt.

If the Chancellor wants to get serious on the public finances, as her decision on the winter fuel allowance suggested she might be, it wouldn’t just be the black hole this year she should be thinking about- she should also be thinking about how to get control of the national debt. Otherwise it will just continue to climb, thousands of pounds per second, hundreds of millions of pounds per day.

…”boost our energy independence, protect bill payers and become a clean energy superpower”

We do grasp how political rhetoric works. String together a few phrases that test well in the focus groups and thereby gain power over everyone elses’ wallets. Been happening since Ur of the Chaldees and we doubt it’s ever going to change much. But it would be nice if the compound message - rather than just the collection of pretty words - made sense.

Apparently we’re to:

Ed Miliband is to add up to £1.5bn to energy bills as part of a record investment in Britain’s offshore wind industry.

….

“This will restore the UK as a global leader for green technologies and deliver the infrastructure we need to boost our energy independence, protect bill payers and become a clean energy superpower.”

We’re to protect bill payers by charging them an extra £1.5 billion? That’s an interesting proof - as in the real meaning, to test - of the contention that renewables are oh so cheap.

But it’s the thing about power there. This is usually referred to as being able to direct the activities of others - as politics has over our wallets. But absolutely everyone is currently spending and subsidising to the same point. That energy shall be produced at home with nowt coming from Johnny Foreigner. If we’re all to be autarkic on our energy systems then no one will have power over another and therefore it’s not possible to become a clean energy superpower, is it?

We mean, sure, it’s possible to argue against Palmerston and his gunboats, we probably would ourselves, but they did actually project power. Whereas a windmill, you know, what do we do, send it to loom over someone? Mince their birds? Or keep them awake at night with the “whoom, whoom”?

Yes, we know, forlorn hopes and all that but before we even get to the discussion of whether politics and planning is the efficient or even feasible method of gaining the goal could we at least all agree that the goal itself has to make sense? #

Tim Worstall

Happy Birthday Milton!

Happy birthday, Milton!

The Nobel economist—and arch-monetarist—the late Milton Friedman, was born on this day in 1912. I was going to write a short biography. But there is one in both of the books that I wrote about him, and it’s not difficult to find all that stuff online.

So I will just say that he was a hugely likeable guy, who relished arguments both with friends and foes, as you could tell by the wide grin he always had while arguing. He would treat students just the same as professional economists, always being keen to engage with them and not talking down to them at all but taking their arguments seriously and trying to raise points they might not have considered. Madsen Pirie and I agree that, while F A Hayek was probably the wisest person we’ve ever met, Friedman was the sharpest—with a quick wit and instant, pithy responses to every point.

So rather than go on about his achievements, let me just let him speak in his own words.

[The] record of history is absolutely crystal clear, that there is no alternative way, so far discovered, of improving the lot of the ordinary people that can hold a candle to the productive activities that are unleashed by a free enterprise system.

Phil Donohue interview

The actual outcome of almost all programs that are sold in the name of helping the poor—and not only the minimum-wage rate—is to make the poor worse off.

Playboy interview

A society that puts equality before freedom will get neither. A society that puts freedom before equality will get a high degree of both.

From Created Equal, the last of the Free to Choose television series (1990, Volume 5 transcript).

Most of the harm that comes from drugs is because they are illegal.

As quoted in If Ignorance Is Bliss, Why Aren't There More Happy People? (2009) by John Mitchinson, p. 8

Ask yourself what products are currently least satisfactory and have shown the least improvement over time… The shoddy products are all produced by government or government-regulated industries. The outstanding products are all produced by private enterprise with little or no government involvement.

Milton & Rose Friedman, Free to Choose, Chapter 7

I say thank God for government waste. If government is doing bad things, it's only the waste that prevents the harm from being greater.

Interview with Richard Heffner on The Open Mind (7 December 1975)

A little inflation will provide a boost at first – like a small dose of a drug for a new addict – but then it takes more and more inflation to provide the boost, just as it takes a bigger and bigger dose of a drug to give a hardened addict a high.

Tyranny of the Status Quo, p.88

If all we want are jobs, we can create any number – for example, have people dig holes and then fill them up again, or perform other useless tasks…. Our real objective is not just jobs but productive jobs – jobs that will mean more goods and services to consume.

Milton & Rose Friedman, Free to Choose, Chapter 2

Few measures that we could take would do more to promote the cause of freedom at home and abroad than complete free trade.

Milton & Rose Friedman, Free to Choose, Ch 2.

Governments never learn. Only people learn.

Statement made in 1980, as quoted in The Cynic's Lexicon : A Dictionary Of Amoral Advice (1984), by Jonathon Green, p. 77

Lab Grown Meats: A New Solution?

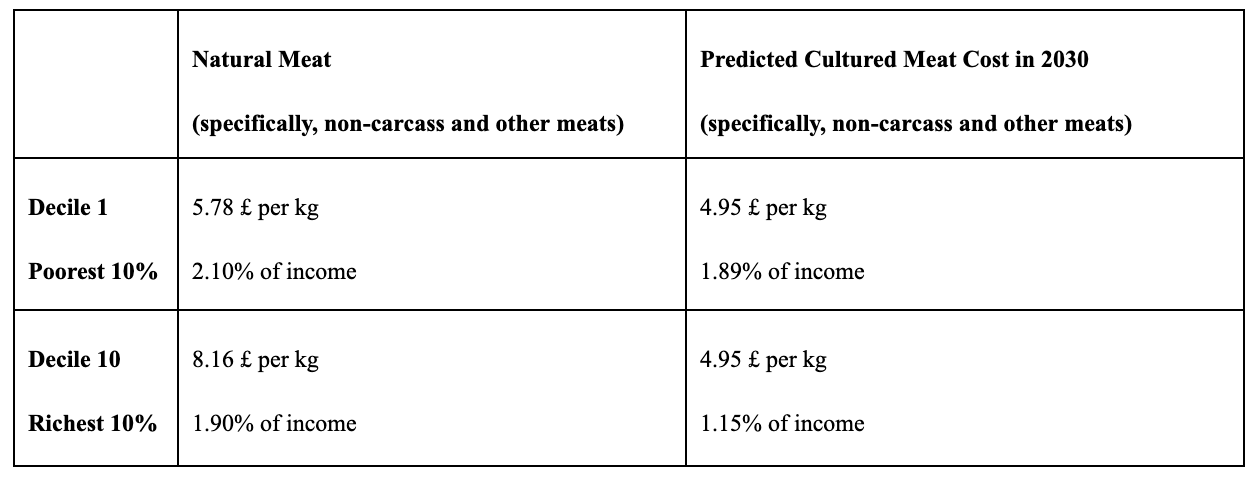

Lab-grown meats are not yet widely considered to be the new solution to the soaring food prices. However, the introduction of this greener and higher tech way to soften the predicted 70% hike in meat consumption by 2050, could be found in cell-cultivated meat production furthering the future of farming. Whilst some consider this innovation to have a Pandora’s Box effect, initiating discussions as to whether such lab-grown meat will be compatible with vegetarians or even Halal meat, the positives for alternative meat provision cannot be underestimated.

It is hard to ignore that, as millions globally move away from subsistence farming, and as there has been an increase in the Westernisation of dietary culture in the face of globalisation, meat consumption in the world population has drastically shifted. Between the years 1964 and 1966, average meat consumption per person per kg in East Asia was 8.7kg. From 1997 to 1999, that value increased to 37.7kg, increasing over 330%. Evidentially, cultivated meats provide a solution to satiate demand without having a toll on the planet, revolutionising the industry physically and economically.

Equally, it is possible to see that the favourable mechanism by which tissue cultures are extracted from the embryonic chicken heart provides the culture with significant nutrients; a technology which could be expanded to increase the lifelikeness of meat production given the appropriate investment, presenting a myriad of opportunities.

One such benefit that cultured meats have is removal of adverse amounts of waste which is becoming increasingly desirable. For example, the fact that we only eat the wings and breast of a chicken is blatantly wasteful, with 16.8 billion remaining chicken carcusses being wasted annually. The ASI’s local Butcher suggests that almost 1⁄3 of every chicken bought is discarded, amounting to almost 4 - 6 kg daily from a singular butcher, illustrating the fundamental wastefulness of the current meat industry.

The benefits that are attached to the modernisation of the agriculture industry cannot be underestimated, with farming fewer animals having the potential to reduce greenhouse gas emissions of gases such as methane and carbon dioxide by almost 78%-96%. Revolutionising one of the most environmentally harmful industries which inefficiently yields products can only be a positive. Cultured meats and their production within sterile labs require 99% less space than the traditional animal husbandry market, potentially saving 17.5 million hectares of the 17.6 million currently used for pastoral land. Such new land could be used for the much-needed housing developments in the UK or alternatively the reforestation of the British countryside is possible. The reduction in monoculture and the polluting disposal of pesticides would further protect the countryside and alleviate environmental concerns.

Equally, animal rights concerns would be relieved at the benefits that this would have on the movement of live animals and the unethical production of meat illustrated by battery hens, satisfying a consumer preference whilst maintaining food production. The important sterile environment would also reduce zoonotic diseases, preventing outbreaks such as the Avian Influenza epidemic of 2021 reducing the number of livestock for consumption. Additionally, lab-grown meat has the potential to protect endangered animals, with the production of synthetic exotic meats devaluing poachers' keep and undermining the black market.

Perhaps most importantly, the greater affordability for the general populace remains significant but equally such modernisation would create the opportunity for ‘fashionable expensive meats’ to be bought up by the rich, satisfying all. Equally, the production of cultured meat and its acceptance into the food industry would predicate great food safety, enabling cultures to be taken from good quality meat and maintain sufficient regulation, as is currently being experienced by the FSA.

The problem currently is the price tag attached to the investment in lab grown meat production, however, with sufficient investment, prices could be a fraction of natural meat, aided by the removal of laborious red tape. Unnecessary over-protective regulations are the outcome of special-interest lobbying by large interest groups put up by Food Standard Authorities generating inefficiency in culinary advancement, as government officials wish to stick to the status quo and limit the potential for outside scrutiny.

Whilst funding for such innovative food production remains limited, with only a few large scale productions such as Mosa Meats’ televised hamburger event, where a €250,000, squashing its pioneering potential; the UK has proven to be on the frontline of domestic production, while only on a small scale. The UK-based pet-food company, Meatly, will begin selling its cultivated chicken to manufacturers as early as this year, setting the UK to become one of the first countries in Europe to commercialise ‘lab-grown’ meat, as a positive movement.

You can read Dr Madsen Pirie and Jamie Hollywood’s longer report here.

Pollynomics never does work, but really Ms. Toynbee this is absurd

The first rule of economics is “Incentives Matter”. At which point:

On the contrary, finding money for productive capital investment in Labour’s priorities for growth, green energy and a housebuilding bonanza

It’s possible to mutter about whether that’s the right goal and all that but let us accept it as the one being pursued. After all, economics doesn’t tell us what the goal should be it just explores ways of getting there.

The frontrunner is raising capital gains tax (CGT)….Why, the IFS’s Paul Johnson asks in his book Follow the Money, is capital gains tax not due on a lifetime of shares, property or antiques, swollen in value but absolved on death?….inheritance tax (IHT) paid by just the wealthiest 4% of estates and too easily avoided: why do pension pots, farms and family businesses escape it?….It’s time to charge national insurance (NI) on all income, not just on pay,….Pensions tax relief is ripe for reform: high earners get 40% and 45% relief subsidised by the state…. Just as a thought experiment, the LSE’s wealth commission shows a one-off raid on wealth above £2m, charged at 1% a year for five years, would bring in £80bn.

Excess wealth and income is there for the plucking

So, if you invest well - profitably, that proof that the investment was a societally useful one - then we’re going to double the share of that profit confiscated. If you don’t bother to sell but keep it for your kids then we’ll take 80% of it (IHT plus CGT). We’ll raise the tax on income from investments by 15 percentage points. Don’t even think about saving for your old age of course - pensions pots being by far the largest source of capital. And if you manage to avoid all of those strictures then we’ll come take your money anyway.

As we say, economics doesn’t tell us what the goal should be, only possible pathways to arriving at the intended destination. Or, of course, pathways that won’t get us there.

So Pollynomics is telling us that the way to increasing productive capital investment is to nick all the money anyone might ever achieve from making a productive capital investment?

This violates that first rule of economics, that incentives matter. But then, you know, Pollynomics, it’s never been any better than this.

Tim Worstall

Nothing makes sense about working hours without household labour

Emma Beddington is merely the latest to miss the damn point here:

I studied economics for a brief, inglorious time 30 years ago – with about as much understanding as a pigeon, actually – but the one bit that stuck was John Maynard Keynes’s assertion that, in future, we would work 15-hour weeks.

So, why hasn’t it happened then? Which is to miss the point that it has happened.

Absolutely nothing will make sense about working hours unless we include household - and unpaid - hours in our calculations. Yes, we leave the house to go work for The Man. No doubt being expropriated of the value of our labour and so on. We also work inside the house without The Man. Childcare, cooking, cleaning, fixing the gutters, digging the veggies, go back a little further and spinning the yarn, weaving the cloth and strangling the pig.

The actual change in working hours in the (near) century since Keynes wrote is that male market working hours have fallen, female market working hours risen. And male household hours have fallen and female household have fallen off a cliff. One estimate we’ve seen is that the weekly labour hours required to run a household have fallen from 60 in about that 1930 to 15 today. The nett effect is that all have very much more leisure than back then.

We have another name for this, it’s the economic liberation of women. Exactly the thing which has allowed women to come out of the kitchen and take their place in government, business, the media and even the military. We think it’s absolutely great too.

The 15 hour week has already happened. It’s just that it happened in that household labour sector, not the market one.

And, well, it just shouldn’t be that difficult to work this out. The Keynes essay does talk about the charwoman, no?

As we have done before we suggest a little test. Talk to some doctors (obviously not professionally, as they don’t see patients any more) and ask how many cases of housemaids’ knee get treated these days? Many more cases of tennis elbow we’re sure, but a vanishingly small number of housemaids’ knee. Well, there we are then.

Tim Worstall

A new bank in town: the approval of Revolut’s banking licence

On the 24th July, the global fintech company, with over nine million UK customers, officially received its UK banking licence, years after it first applied. Whilst Revolut securing a licence is a positive step towards the liberalisation of banking and giving the average person greater freedom of choice, this begs the question as to why this has taken so long.

The news about Revolut’s banking licence approval has been met with great support for diversifying the current banking market, however, the addition of a singular bank falls short of neighbouring countries, such as Germany. The German economy benefits from the thousands of licensed banks compared to the five banks that make up Britain's banking and financial services, making the UK’s banking network one of the most homogeneous in the world. The small number of banks available to the general public has somewhat monopolised the arena for which the average consumer in the UK has very limited choice. In fact, the five leading banks—Lloyds Banking Group, RBS, HSBC, Barclays, and Santander—have an 85% share of the personal current account market, illustrating the limitations for the consumer.

Revolut, who has 45 million worldwide customers, already had licences in Lithuania and Mexico. It now hopes that the UK’s approval will help it to expand its activities in key markets like the US and Australia. It had filed a licence application back in early 2021 but had faced substantial setbacks. The reasons stated included trouble with revenue verification, following delays to the 2021 and 2022 accounts being released, as well as the departure of senior executives and the ownership structure. The entry of Francesca Carlesi, former Deutsche Bank executive, into the company’s leadership back in November has helped subdue the technocrats at the Prudential Regulation Authority (PRA). While there is the argument to be made that filing an earlier application, when the company had been much smaller, which may have helped it secure its licence faster, the argument fails to remove the fault resting on the overly stiffened bureaucracy taking so long to approve one of the most trusted Electronic Money Institutions in the UK.

The company differs from more traditional banks in its focus on primarily online banking - a move which has drawn customers through its accessibility and ease of entry. It is in talks to sell $500mn worth of shares in the hopes of boosting its market valuation from $33bn (as valued in 2021) to $45bn - a move which, if successful, might make it a contender for third place among UK banks, replacing Barclays and being only surpassed by HSBC and Lloyds Banking Group. However, there are growing concerns that the current macroeconomic environment, with a drop in interest rates expected soon, might reduce Revolut’s profits. Considering the fact that interest income had accounted for over a quarter of the company’s revenues last year, this may pose worries.

The three year wait for Revolut’s licence exemplifies the red tape delays in the British banking market produces and, despite the longevity of the wait, the licence provided comes with significant restrictions, meaning that new products from Revolut will be unable to be launched, further limiting the choice of individuals. The Bank of England’s suggestion for the movement into the mobilisation stage, provisioning a conditional phase allowing for finalisation of the IT infrastructure, governance, and risk management frameworks. Revolut must attempt to secure further investments but in the meantime this phase allows greater protection of the Financial Service Compensation Scheme (FSCS) for customers. It must be noted, that the provision of the mobilisation phase does not allow for the complete success of the liberalisation of the financial sector, rather further illustrates the struggle that innovative banks face in licensing agreements.

Whilst Revolut’s licensing has the potential to benefit UK customers, protecting their money, the need for greater removal of red tape around regulation on businesses is essential to economic growth, with the overcomplicated nature of the regulation strangling businesses and growth in markets. The need to reassess British financial markets is becoming ever more obvious and therefore necessary to boost the economy through greater competition between a multitude of banks and attract greater investment, something which the government’s slow pace of reform is limiting.