Those Laffer Curves seem to be coming home to roost

Unlike England’s footie, economics is coming home.

Labour’s non-dom plan could raise no extra funds, officials fear

Cost of super-rich leaving UK may exceed money raked in by new system, say Treasury sources

Oh.

Keir Starmer’s promised tax crackdown on non-doms could yield no extra funds for the Treasury, leaving a £1bn hole in the government’s planned spending for schools and hospitals.

Labour planned to use the money raised from wealthy individuals who are registered overseas for tax purposes to invest in ailing public services.

But the Guardian understands that Treasury officials fear estimates due to be released by the government’s spending watchdog may suggest the policy will fail to raise any money because of the impact of the super-rich non-domiciles leaving the UK.

Gosh, so the plans of the mice have ganged agley, have they? As Herr Hayek was known to remark, planning is difficult.

At which point your standard reminder. Every tax has a Laffer Curve. There’s a point at which the bite being taken changes behaviour. This is just the first lesson in all economics - incentives matter. At some point people will slow their work. Stop working. Take less risk. Go fishing. Talk to their own wives (shudder). Leave the country. Something. What that point is will depend upon the tax, the surrounding environment, the other attractions of it and so on.

The European Union itself famously proved that a Financial Transactions Tax at 0.01% was above the revenue maximisation point. The IFS has shown that stamp duty on shares at anything above 0.0% is above that revenue maximising point. And here we’ve the claim at least that taxing non-doms as if they’re locals is over that peak of the Laffer Curve.

We can’t shore up the system either, not with non-doms. The whole point is that they already get charged local taxes, in full, on local assets and incomes. It’s only their foreign stuff that doesn’t get taxed in the UK. And there really is no way that we can tax foreigners on foreign assets or incomes if the foreigners return to living in foreign.

The Laffer Curve(s) exist and they’re important. It really is possible to try to tax so much that you collect less revenue.

Ho well, back to the drawing board, eh?

On that drawing board there does need to be this thought. If charging non-doms the amount that they would have to pay if they were dom is over the top of that curve then is the amount of tax we charge to doms already also over that peak? Inquiring minds would like to know and we’re really rather sure the answer is “Yes”.

Homes for Heroes - the Prime Minister needs a history lesson

Or, if it were not for the fact that we’d never say such a thing about one so distinguished, the Prime Minister needs to be boxed about the ears until he grasps the problem. The announcement that the government is going to build homes for heroes - we approve, as do veterans. So, good.

Except that phrase has been used before. Lloyd George’s promise during WWI of “homes fit for heroes” became Homes for Heroes in the early 1920s. Then as now an entirely valid plan and political goal. It’s just that for one of us that whole story tells us what has actually gone wrong - howlingly, horribly wrong - with British building in this past century. Or, perhaps, what it is allowed that people may build.

Along one particular street in Bath, along Englishcombe Lane, it’s possible to see that gone wrong.

If we’ve managed to get Google Streetview right at the bottom of the road, some very grand late Victorians and Edwardians. Just opposite is part of Morlands, which is a 60s or so development by the styles of that time. No private space at all, no front or back gardens, no room to put the dog out, not even a flower bed. Houses on a council lawn that is. Ho well, socialists and private space, eh?

The more apposite point is that a couple of hundred yards up the road are those post-WWI homes for heroes. Here. Semi detached, not huge to be fair. But kitchen, living room, parlour, 3 beds and indoor bathroom. They’re still highly desirable houses in fact. Note, they’ve front gardens. They’ve also back ones too.

Now, we’ve heard this, even heard it from someone on Bath City Council (who had heard it, we’re not quite old enough to know anyone who was on BCC in the 1920s), and never, quite tracked it down officially. But the statement was made that the Homes for Heroes needed to be on 1/4 acre gardens. The working man needed the space to grow vegetables for his family and to keep a pig. These houses, the 1920s ones, do have substantial gardens as the 1960s ones don’t.

We can then carry on up this same road, to here. Perhaps 70s or 80s houses. No, no, not 1880s, 1980s. Note the wholly trivial size - and no, they do not have decent back gardens. The road at the top is called Whiteway. And a couple of hundred yards along that - please do note that all these locations are within hundreds of yards of each other - we’ve a view of Englishcombe itself. Which is, of course, free of housing because that’s Green Belt, that is. It would strike terror into the heart of the haute bourgeoisie if we ever built upon that - even if it were Homes for Heroes, let alone something better than a rabbit hutch for the proles.

And this is what is wrong with housing in Britain. Yes, yes, of course, not everyone’s going to live in a grand Edwardian. Yes, yes, we can fail to replicate those mistakes of when we allowed the sociologists to miss the point in the 1960s - personal, defensible, space is important to humans. One little thing - all our examples are council housing here.

But Homes for Heroes? We’ve done this before. And those Homes for Heroes? Right now, today, it’s illegal to build them. No, really. What was considered the basic minimum that the local council should provide to the working man is illegal to build now. Those decent sized houses were on those decent gardens d’ye see? You can get perhaps 9 dwellings with 1/4 acre gardens on a hectare of land. Last we saw the current insistence is that we must have no less than 30 dwellings per hectare in order to gain planning permission. Even though Englishcombe - as with so much other land - is there and ripe for the taking.

It’s actually illegal to build houses that were regarded as the proper minimum a century ago.

That’s the problem with British housing. It’s simply not legal to build anything that our grandparents thought was the necessary minimum, let alone better.

At which point we change our minds. Yes, the Prime Minister - whoever it is - needs to be boxed about the ears until they understand the problem. Then, of course, the boxing needs to continue until they actually do something about it.

Homes for Heroes is a great idea. But an entirely serious and sensible suggestion. Anyone and everyone involved needs to go see what our forbears built for that same reason a century ago. Then wonder how we’ve ended up with a system that makes building just that - a house with a garden for the working man - illegal.

No, really. Think on it. Really? How did we get into this state? And shouldn’t we be boxing the ears of every Prime Minister that allowed this to happen?

Tim Worstall

The average today is higher than the living standard of 19th century royalty

For those of us in Europe and offshoots - generally what we call the developed world - yes, this is true. We do live better, on average, than the average 19th century royalty.

This is a claim that some will guffaw at. Yet it is still true.

In a number of ways it can be claimed we don’t - we’re not living in palaces for example, nor festooned with diamonds. We also don’t have to put up with German princelings which is nice.

In a number of ways we’re about the same. For the average of us we’re well fed, well clothed and so on. As were those royals.

But in a number of important ways we’re better off.

We have the entire wisdom of mankind to hand, immediately available for example. But not just smartphones, we’ve just phones, something the average decade, let alone royal, of the 19th cent didn’t have. And jetplanes, and even planes themselves - it would be interesting to find out if there was actually an exception to the statement that no one regnant in the 19th century in any country ever got on an airplane. Transport, communication, vastly better these days.

But they had servants, right? But we’ve mechanised those servants - the washing machine, the electric stove, the steam iron, vacuum cleaner. By and large we’d consider that a wash (sorry).

But two things really stand out that are different. The first is that we are hugely, vastly, warmer. Those palaces were never known as being warm - there are lovely stories from the beginnings of the National Trust that those big old houses were freezing cold in general. We’ve seen, recently, an argument that the average across the property temperature in winter was 0 oC. It was only actually in front of the fire that it got up to 10 oC. Those old high backed chairs were to keep your neck warm from the draughts, d’ye see? The very design of porter chairs tells us that significant areas of the house were not warm.

In fact, everyone - including royalty - was in what we would today call fuel poverty:

Adequate warmth is considered to be 21 °C (70 °F) in the main living room and 18 °C (64 °F) in other occupied rooms during daytime hours, with lower temperatures at night,

It’s not a matter of money, simply not technically feasible to heat a place to those levels back then. Actually, anyone who grew up - however bourgeois or aristocratic - more than 60 years ago will have been in fuel poverty by that standard.

But the real biggie is health care. Antibiotics more than anything else. In the 1920s the son of the President of the US died of a blood blister. Childbirth cut a swathe through royal as other families - it’s the reason we got the Queen Vic. It’s generally although not wholly true that a health care system could really only do bed rest and hydration until we gained those antibiotics. And to return to childbirth, Viccie again was one of those whose use popularised the new anaesthesia in childbirth. Before that all births were natural, even to the most highborn. And let’s not even go to child mortality, something that claimed near half of all children before puberty - lower levels for royalty of course, but still at levels that would be considered a holocaust today.

We do live better lives than the average 19th century royalty. Given that the NHS is currently the national religion we must do as we do have medical care.

But as so often, PJ O’Rourke:

In general, life is better than it has ever been, and if you think that, in the past, there was some golden age of pleasure and plenty to which you would, if you were able, transport yourself, let me say one single word : Dentistry.

There’s a reason none of those royals in that first half century of photography smiled and said “cheese”. None of ‘em had any teeth.

Solved it: The Chancellor should charge CGT on gilts

As we all know there’s a certain hunger for more tax money out there. So, we should think of new ways to gain more tax money, obviously - the idea that anyone’s going to just spend less is absurd, equally obviously.

We’re also told that the richer should be paying more tax on those absurd profits they make from investing in things. Capital gains tax should be the same as income tax and at the top end this means 45%. Let’s just call that 50% for ease of calculation in what follows.

There’s an about £400 billion* (again, let’s just play with very rough numbers) profit that investors are going to make. All of which will be CGT free. So, we should tax that £400 billion.

The Bank of England owns some £800 billion in gilts. The latest announcement is that they’ll sell £100 billion of this in the coming 12 months. The capital loss is said to be around £50 billion (again with the very rough numbers). This is because those gilts were bought when interest rates were 1 and 2%, now they’re 5%. The loss is already baked in - it’s possible to collect that loss year by year on the difference between the 5% being paid out to banks on reserves and the 1 or 2% being collected. Or, the bonds can be sold and the loss taken as a capital loss. Same difference, different accounting year is all.

OK. But that capital loss will be a capital profit to the buyers. The total return to the buyer will be the 1 or 2% interest coupon plus, obviously, the rise to par value of the bond as it approaches maturity. So, if the BoE is to lose £400 billion here then investors must make £400 billion. The bonds are to be sold at, say, 50% of face value and they’ll mature at 100% of it.

But here’s the thing. That capital profit on gilts is untaxed. Entirely so. It’s also concentrated among the rich. It’s entirely possible for individuals to buy gilts but the poorer tend to go with NS&I instead. It’s the richer, in larger size, that go for gilts.

So, whack CGT on gilts and collect £200 billion over the years. Job’s a good ‘un and the problem is solved, right? After all, why should the rich gain access to a savings opportunity with the government without paying tax for the privilege?

Glad we could help out here.

Hmm, what’s that? There’s a reason there’s no CGT on gilts? In order to encourage investors to buy them? And taxing gilts would make investors less likely to buy them you say? But, but, that would mean that the tax rate on investing changes the amount of investment done, right? And we’re all agreed that we insist upon having a high investment, high productivity Britain, right? So increasing the CGT rate on private sector investing will reduce the amount of private sector investing and thus damage that aim of a high investment economy. Yes?

Well, isn’t that a pretty pickle. Experience tells us that zero CGT on gilts increases investment in gilts. We’re also being told that more than doubling CGT on non-gilts investments will aid us in increasing the amount of investment in our economy. Logic tells us that both can’t be true at the same time.

So, who to believe, eh, who to believe?

We’d suggest it’s the rather hard headed folk who have to write the cheques to those who do invest in gilts. The Bank of England, Debt Management Office and the Treasury. They would all be absolutely horrified at the idea of CGT on gilts. Because they know, very well and absolutely, that this would reduce investment in gilts. Therefore, if we want a high investment economy we need to be reducing taxes upon investing, not raising.

But then logic and government, so, so, difficult to get the two aligned.

Tim Worstall

*Yes, yes, we know, most of the holdings are inside some tax wrapper. This is an explanation of the logic not a real world calculation of the numbers.

Asset stripping is recycling, so why the hate?

From a man who teaches at a British univerity, much to our perplexity:

The reality is that private equity is not the best of capitalism, as it would like to pretend. Back in the 1970s it was described as what it really is. The description commonly used then for those undertaking this activity was ‘asset strippers'. Nothing much has changed, except the scale of the activity. Despite that, asset stripping is what it still is.

Clearly, the implication there, the intended meaning, is that asset stripping is something bad. When, in fact, it’s the recycling of economic resources.

Recycling is good, right?

Think through how a market economy works. There are varied economic resources - land, labour, capital being the usual trio - that are combined in different ways to try to achieve some goal. Not all of these tries work. This is the very point of a market economy, that the different combinations, methods and tries get, erm, tried. Then we do more of what works and less of what doesn’t.

But that does mean that there are those combinations that we do less of. In fact, there are those failed experiments that we’ve got to stop. Which means that those scarce economic assets we’re currently using to do something not worth doing need to be extracted, recycled and moved off into some other usage which produces value.

That is, asset stripping is not just an entirely valid part of capitalism, it’s also not just a desirable one, it’s one that makes us all richer. After all, moving an asset from a lower to a higher valued use is the very definition of wealth creation.

Odd how people who actually teach in universities can fail to grasp the basics really.

Tim Worstall

If we could just suggest something to Mr. Peston?

If you are going to start complaining about the tax paid by some corporation do, please, try to have at your side someone who has a clue about corporate taxation:

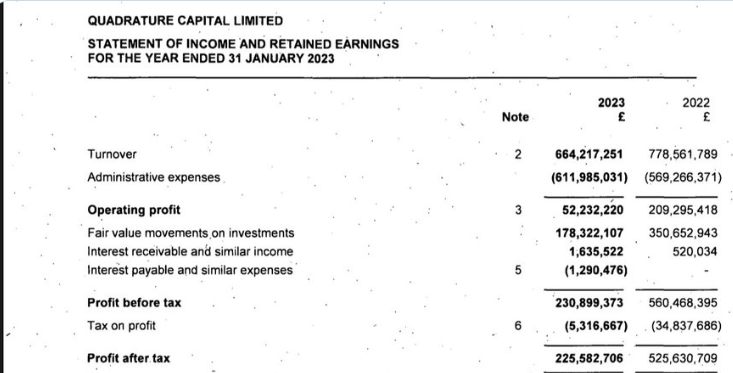

Quadrature Capital Ltd made a £4m donation to Labour on 28 May 2024. It was reported to the Electoral Commission on 30 July 2024. It has only just been revealed by Open Democracy. I have just looked up Quadrature’s UK accounts. The firm says it’s receives remuneration for “investment management services” and that profits are driven by “the performance and assets of the funds under management”. According to its most recent filings (see attached) it paid tax of a paltry £5.3m in 2022/3 on profits of £231m and just £35m of tax on profits made in the previous year of £560m. In other words it has been paying a fraction of what was the UK corporation tax rate of 19% - which at the time was low by UK standards. There will be Labour members and supporters who will be surprised and disappointed that the party is funded by a business that pays considerably less in tax than the official rate.

They’re an investment management firm, as you say. Which means that they manage investments for people. Those investments will change in value over the course of a year - this is rather the point of hiring the company to do the managing of investments. Which is the bit that’s been missed in the analysis.

The “fair value movements on investments” is not taxable. Because it’s not a realised gain. In exactly the same way that you are not charged capital gains tax if your shares go up - but are charged CGT if you sell shares that have gone up and thereby take a profit. You are not charged tax every time your house changes in value. You might well be when it is sold and you book the profit (second homes etc). Profits that stem from marking to market are not taxed. Profits that are realised are.

This is different from what you get to say to shareholders and potential customers - there, of course, you do want to say “Look, number go up!” and good luck to you as you do so.

We do know that this is quaint, even old fashioned. But we do still run with the idea that the purpose of journalism is to inform.

Tim Worstall

Introducing Greenpeace to the concept of sums

There are many ideas out there about how to make the world a better place. Some of them might work, most won’t - just one of those little tragedies. We need - and have - methods of trying to work out which is which. One method is our own favourite, simply use the market. The interactions of 8 billion people will pretty quickly come to a conclusion. But if our guess at making better is an intervention into markets then we do need to at least try to do some sums.

Renationalising the railways does not go far enough – Labour should spur a rail renaissance by allowing people around the UK unlimited train travel for a flat fee, campaigners have said.

Under a “climate card” system, passengers could pay a simple subscription to gain access to train travel across all services. This could be effective if set at £49 a month, according to research published on Thursday, though travellers on fast long-distance trains and those on routes in and through London would need to pay a top-up to reflect the greater demand on those services.

If such a system were implemented across the UK, it would be likely to result in a loss of revenues to the railways of between £45m and £637m, depending on the uptake, the report found. This would have to be subsidised by the government, but transport is already subsidised in various less effective forms, and the report found the climate card would generate economic growth and improvements to health from lower air pollution.

Well, OK, it’s an idea. The report is here. No, we’ve not checked, but we’d suspect that the numbers are done on one person in a car and everyone in a full train - rather than a full car and a half empty train. That’s just our prejudice there because that’s how these numbers are normally done.

But OK, let’s assume they’ve not done that. So, the benefit is:

This mode switching would result in a reduction of 378.7 thousand tonnes of carbon emissions (CO2e).

OK. We know what the value of a tonne less of CO2-e is - $80 because the Stern Review told us so (we think it’s true that this is actually higher than the number the govt currently uses as a shadow price - think, note). The value of the emissions reductions is £30 million therefore. The cost is £45 to 637 million. Or, if we run this back the other way, the cost of the CO2 reduction is $120 to $1,700 a tonne.

The value of the reduction is $80, the cost is up to $1,700. No, this is an idiot thing to do. Therefore don’t do it - doing things where the cost is greater than the value is known as making us all poorer.

Don’t forget the other thing the Stern Review told us. We must be efficient in our reaction to climate change. We must find the lowest cost methods of reducing emissions. Because - we’re all just odd this way - humans do more of cheaper things, less of more expensive. Using expensive methods to beat climate change will lead to less beating climate change - using less expensive methods more. Exactly and precisely because climate change is so important means we’ve got to concentrate, real hard now, on beating it efficiently.

So, no, idiot idea. But then Greenpeace and sums, eh?

Tim Worstall

Of course we should stop subsidising bad things

We’re a great deal more sympathetic to this argument than most will think we are:

The world is spending at least $2.6tn (£2tn) a year on subsidies that drive global heating and destroy nature, according to new analysis.

Governments continue to provide billions of dollars in tax breaks, subsidies and other spending that directly work against the goals of the 2015 Paris climate agreement and the 2022 Kunming-Montreal agreement to halt biodiversity loss, the research from the organisation Earth Track found, with countries providing direct support for deforestation, water pollution and fossil fuel consumption.

Yes, obviously, we should not subsidise bad things.

Now we’re a lot more sceptical about those international agreements than many. That all the meetings are held during Northern Hemisphere winters in nice low latitudes seems something of a hint to us - it can’t always be the existence of significant air traffic connections, can it? But leave our general scepticism of the process out of it.

We don’t want to be doing bad things let alone subsidising them. So, if the thing is a bad thing then we should obviously not be increasing usage through subsidy. We’ve no problem at all with that chain of logic.

The report itself is also pretty good on what is a bad thing and what is a subsidy to it. We’d not do so far as to say completely right, but rightish at least. The biggie - getting on for half the total - is subsidies to fossil fuels. And yes, obviously, these should stop.

But the thing they’ve got right is the identification of what is a subsidy. We’ll all recall that $7 trillion number The Guardian shrieks about but that’s not what is used in this report. Instead of a subsidy being “not paying a carbon tax and also full consumption taxation” which the IMF uses as their definition here a subsidy is an actual, direct, cash out the door, subsidy to the use or production of fossil fuels.

As it happens we here in the UK doesn’t have those by the IMF definition subsidies on petrol and diesel so we’ve nothing to do here. Well, now we’ve stopped subsidising domestic energy bills at least. It’s also true that we - again pretty much and near totally - don’t have any subsidies to fossil fuels by this narrower definition. OK, we here in the UK are being good chappies and we’re done then.

It’s the others, out there, that need to up their game on these subsidies. We’re already done.

Which leads to just one of those niggling little thoughts. The argument in favour of us spending £ trillions on birdchoppers and a zero carbon grid is that Johnny Foreigner will, staggered by the immensity of our moral leadership, then do the same. Yet we’ve already stopped subsidising fossil fuels and they aitn’t. So there could be a hole in the logic here. Anyone got a contact number for the planet the Sec of State is currently residing upon?

Tim Worstall

Markets unadorned don’t always work, no

We all know very well that - well, we all should know very well that - a pure free market in pharmaceutical drugs simply will not work. It costs $2 billion to do the research and gain authorisation to sell such a drug. It costs perhaps $5 to make a dose of said drug - often enough 50 cents. So, if anyone and everyone could simply make the drug once approved then no one would spend the $2 billion. Therefore patents on drugs.

Yep, quite right, those who - or their health care systems - need the drugs right now are held to ransom to pay that $2 billion. The saving grace of the system being that the patent protections mean we do get new drugs. The patent lasts 20 years, it takes 10 years to get to authorisation, so after 10 years of being in use that patent lapses and everyone can make the drug for that 50 cents.

It’s possible that this is not the very best system possible. But the point to be made is that this clearly and obviously a constructed market. We have invented, out of whole cloth, that idea of ownership of the proof of authorisation in that patent. This isn’t a right that exists in nature, it’s something we’ve invented to try to make the system as a whole work better.

That is, people can be entirely right in claiming that good government can make markets better. Indeed this is true.

Almost a century on from the groundbreaking discovery of penicillin by Alexander Fleming, his scientific successors are racing to save modern medicine.

Infections that were once easy to cure with antibiotics are becoming untreatable, and a novel treatment for bacterial infection is the holy grail for teams of researchers around the world.

However, severe financial challenges have left the pipeline of new antibiotics thin and fragile – and treatments are unavailable in many of the places they are most needed. Big pharmaceutical companies have left the field in search of greater profits elsewhere, and talented researchers have opted for new jobs in more stable sectors.

This is a problem. The really big one here being that the financial incentives of that patent conflict, mightily, with the medical incentives. As and when someone has spent that $2 billion to get a new antibiotic to market we don’t want them selling the heck out of it for 10 years to make that money back. Instead, we want this new drug to be used as sparingly as possible - preferably never in fact - so that we don’t promote the evolution of the bugs to be resistant to it. We want that new and fully effective antibiotic to remain fully effective by not using it, or only using it when all else has failed.

Our constructed market doesn’t work for new antibiotics. OK then:

The issue needs incentives that push innovation, De Felice says, such as grants to support early-stage research from governments and the third sector.

It also needs incentives that pull drugs through to market and guarantee companies a return on their investment, even if the antibiotics are not used but held in reserve as a last resort for particularly severe infections.

Some of those programmes exist already. In the UK, drug companies can receive a fixed annual fee for new antibiotics regardless of how much they are used. The subscription model bases payments on how valuable the drugs are to the health system.

So, a new market is being constructed. This looks like it will cure that specific problem but of course it may not. So, continual innovation in the market itself is something we should at least hope to aim for.

The larger point here being that it is not true that the market fails. Rather, specific markets, given their structure and incentives, can fail. If that’s so then the correct answer is to construct another market with different incentives.

For example, we all know that Nick Stern comment upon climate change - the biggest market failure ever. At which point the Stern Review doesn’t say abandon markets, it recommends constructing a new market, with the correct incentives, by having a carbon tax.

Markets fail so use markets.

Of course, there are even some things that markets cannot handle. Say, keeping the French at bay so government should indeed run the Royal Navy. But these things are few and far between - unlike the beliefs of those who twitter on about strategic plans with strict conditionality.

Tim Worstall

This week’s prize for obdurate stupidity goes to….

And it’s only Monday as we write:

Campaigners have urged the chancellor to start taxing jet fuel – with a report showing that charging duty at the same rate paid by motorists would raise up to £6bn a year for the public finances.

An analysis by the thinktank Transport & Environment (T&E) UK said introducing a “fair” equivalent to the fuel duty paid in other sectors could raise between £400m and £5.9bn a year, based on the 11m tonnes of kerosene consumed by planes taking off from the UK in 2023.

It’s entirely true that jet fuel is not directly taxed. But we do have Air Passenger Duty:

Air Passenger Duty, a duty unique to the UK, was introduced in 1994 by the then chancellor of the Exchequer, Kenneth Clarke. Clarke regarded it as anomalous that fuel duty was not levied on air transport, but international agreements prevented his levying a duty on aircraft kerosene. As an alternative, Clarke introduced Air Passenger Duty, a levy collected by airlines on passengers who start their journeys at UK airports.

As with skinning cats in the Mid West there are many ways to tax something. APD is the method we use to tax jet fuel. Annual collection is heading toward £4 billion.

In the paper from the not thinking very much tank, Transport and Environment (UK), there is no mention of Air Passenger Duty. Not one.

Yes, today’s only Tuesday, we’ve only had Monday’s examples to consider for nominations for this week’s prize so far but we are going to have to award that prize for obdurate stupidity to T&E (UK) we’re afraid. For we really do think it most unlikely that anyone’s going to beat this in only 6 days.

No, please, do not take this as the start of an hold my beer challenge. We are indeed pretty robust but there is still only so much we can take.

Tim Worstall