Britain needs more slums

The problems with the UK housing market have been well-documented. There is a 'housing crisis.' No-one today can afford to buy the sorts of houses their parents did. Household formation is depressed. Every day, the reports get more lurid. The latest example of this is a survey suggesting that all 43 of the affordable houses in London aren't actually houses, but rather boats. There has been a proliferation of not-houses in recent years, from houseboats to 'beds-in-sheds.' The reason is clear – Britain has a sore lack of proper slums.

Government regulations designed to clamp down on 'cowboy landlords' restrict people's ability to choose the kind of accommodation in which they want to live. Local authorities impose exhaustive energy efficiency standards, design codes, and depress density – if they allow construction at all. Each individual requirement sounds fairly reasonable, something that almost everyone would want. But housing should cater to a wide array of preferences. Some people might not feel like they need a bedroom space as large as the state expects, while others might not mind sharing a bathroom with another family if it means lower rents.

The consequences of forcing people outside the law are serious, as with immigration. If the only way you can afford housing is to live illegally, you have no recourse to the law if you do have a dispute with your landlord.

These regulations don't just affect the type of squalid accommodation that they were designed to outlaw. A recent project to build 'micro-flats' worth up to £231,000 required the intervention of the London Mayor to exempt it from certain regulations. Developments like these might be the future for young people like me struggling to get onto the housing market, but this kind of ad-hoc policymaking is no way to run a country. Wholesale change is needed.

The market desperately wants to provide houses people can live in at prices they can afford – but in the eyes of local authorities these houses are too small, or too tall, or the ceilings are too low, or the windows not energy efficient enough. Sweeping deregulation is the only way to provide Britain with the slums it is crying out for.

Theo Clifford is winner of the 18-21 category of the ASI's 'Young Writer on Liberty' competition. You can follow him on @Theo_Clifford, and read his blog at economicsondemand.com.

Can we really decriminalise sex work, globally?

Amnesty International have released a draft policy arguing for global decriminalisation of sex work. As a rule, decriminalisation of consensual actions between individuals that do not directly harm others is something I support. Prioritising the removal of legislation that disproportionately hurts the worst off/most marginalised is top of this agenda. However, wading into an unfamiliar political landscape and applying libertarian principles without care for the consequences is not something I endorse. In this case, I think Amnesty have missed a trick on nuance, in mandating a global recommendation for decriminalisation. In a previous paper, Amnesty say:

Approaches that categorise all sex work as inherently nonconsensual, actively disempower sex workers; denying them personal agency and autonomy and placing decision-making about their lives and capacity in the hands of the state. They also limit sex workers’ ability to organise and to access protections which are available to others (including under labour laws or health and safety laws).

Arbitrarily broad laws prohibiting organisational aspects of sex work often ban sex workers from working together, renting secure premises, or hiring security or other support staff, meaning that they face prosecution themselves if they try to operate in safety.

This is a sound argument for decriminalisation. Even those who think that we should categorise sex work as nonconsensual should nevertheless see that at least decriminalising it makes it safer (since we can regulate and sex workers can report illegal behaviour without fear of prosecution themselves!).

There are two main criticisms of Amnesty’s plan. One is the fact that they somehow see the needs of buyers as relevant to how we should treat sex workers (i.e. because some clients of sex workers often purchase these services because they would otherwise struggle to enjoy them unpaid, we ought to consider making it easier for them to do so). I sympathise with this concern - nobody has the right to sexual gratification, so the idea of legislating with this in mind just seems bizarre.

But the main reason to be sceptical of Amnesty’s call for decriminalisation globally, is that they don’t appear to have done an awful lot of research to understand whether decriminalisation is right everywhere.

Sure, it’s very likely to be a good idea in the UK and most European nations. We can debate the merits of various regulatory frameworks to put in place once this has gone ahead. For example, despite concerns that decriminalisation would lead to more prostitution, and more visible prostitution, the evidence in New Zealand post-decriminalisation does not support this. From other countries, we see that police are a huge source of violence against sex workers (the study attached to that link is very graphic) and by the admission of police and sex workers themselves, the lack of access to justice for sex workers is a huge problem. If decriminalisation makes any headway in increasing sex workers’ ability to use the legal system to assert their rights, this is a step forward. The BMJ recognises that decriminalisation improves sexual health for sex workers.

But in every other policy debate, we would always consider whether the subject of our enquiry differs depending on the context in which we’re applying it. Do cultural, social, economic and legal differences between countries inform the kind of effect we might expect decriminalisation to have? It is impossible for them not to have a huge impact on the success of decriminalisation.

Consider the example of a country where the stigma attached to sex work includes serious bodily harm to the sex worker by aggrieved members of the community to which they belong. By criminalising sex work on the part of the buyer (commonly known as the ‘Swedish’ model), you increase the incentive for the buyer not to ‘out’ the sex worker, which may actually make the sex worker safer. The example of Cambodia gives us reason to suspect that it isn’t as simple as decriminalising - according to the same source, Cambodia is highly restrictive of women’s sexuality, which indicates that decriminalisation is not going to deliver the benefits we might hope for, and might do much worse if society takes the police’s place.

Imagine a situation in which decriminalisation would actually result in higher people trafficking, masked as sex work to reduce the legal repercussions. Criminalising the practice, either by punishing organisers of sex workers or by criminalising buyers may result in higher welfare for sex workers particularly as it discourages their exploitation. In Sweden, anecdote suggests that traffickers are seeing it as a less profitable place to operate, suggesting that there are some perks to criminalising the purchase of sex whilst not criminalising the sale - this kind of outcome might be appropriate for countries which have particular concerns about people trafficking, or whose current legislation makes it difficult to appropriately address trafficking. Again, though, it raises the worry that this second-best policymaking actually targets the wrong problem and is evidence that Sweden hasn’t got to grips with trafficking and is having to do so via indirect means. We also need to worry whether global trafficking volumes have changed - or just been moved elsewhere, to places where perhaps women don’t have the same degree of access to justice.

This isn’t to say we shouldn’t aim for decriminalisation in the long-term, but to recognise that there are a number of factors which will get in the way of achieving the aim we are pursuing in decriminalising in the first place - advancing the autonomy and, hence, safety, of sex workers. When embarking on a full-scale decriminalisation, perhaps we ought to consider addressing those problems concurrently. Certainly, Amnesty shouldn’t be mandating what the entire world should be doing with such insensitivity to the cultural, economic and legal norms of the various nation states that might alter the consequences of decriminalisation.

If only the warmists bothered to read the actual research

Talking about climate change inevitably brings up huge shouting matches. But let's put that to one side for a moment and just start insisting that those who do urge action on it actually read the reports that lead to the urging of action. As The Guardian quite obviously isn't here:

The fact is that it is in the very poorest countries where women have the most children, on average. And where population growth slows, generally economic growth speeds up, and carbon emissions rise faster. This happens on a global scale and even within countries – certainly within the poorer ones where there is most scope for population control, and where, also, the potential for industrialisation is greatest. It is unclear which is cause and which is effect: it is likely that they play off each other. And in some cases, perhaps, population policies go hand in hand with economic reforms. Only in the wealthiest countries, though, which already have lower fertility rates, are these links weakened or even broken.

This phenomenon raises the counterintuitive possibility that curbing population growth could generate higher global emissions than would otherwise be the case.

No, that's not something you're allowed to do. For, as the SRES, the economic models upon which the whole game is based, have entirely the opposite assumptions baked into them. A richer world has a smaller population. And those richer, smaller, worlds have lower emissions than poorer and more populated ones. Other than the entirely extreme world of A1FI that is (and really, nobody believes that coal is going to provide 50% of energy in 2100).

Economic growth leads to falling fertility and thus a smaller future population. The combination of these two is part of the solution to climate change, not part of the problem.

It is, of course, fine to have differing views on the subject itself. But we're adamant that whatever your views are they must at least be consistent with the evidence that leads you to them.

There is no right time to sell the RBS shares

This is a simple point, but it’s one that some people who should know better seem to keep getting wrong. Share price movements are unpredictable and there is no more reason to think the price of shares will be higher next year than to think that they’ll be lower. Which means that there is no ‘right time’ for the government to sell its RBS shares. If we thought that RBS shares would each be worth 50p more by Christmas then we’d be buying them now and bidding up the price towards 50p now. The price wouldn't quite reach 50p because there's still the chance that we're wrong.

And indeed that is exactly what happens, and why we can only assume that share prices reflect what we expect them to be worth in the future. Because share prices can go down as well as up, we get a return from investing in the stock market above what we get if we invest in safer assets, like government bonds.

You would think this was obvious, but the BBC quotes:

Ian Gordon, a banking analyst at Investec, told the BBC's Today programme: "The taxpayer is being short-changed." The shares could have been sold for a higher price in February, when they were changing hands for more than 400p, he said.

But of course we had no idea in February that they would fall, and we have no idea what will happen to them next. Like the Royal Mail shares they might rise after we sell them off, or they might fall. Or they might not move at all.

BusinessInsider’s Mike Bird makes this point very well, and as well as reminding us that the RBS bailout was always going to be a money-loser, he points the people who think we can just wait and hold on to the shares until they rise back up to their 2008 level to this chart showing RBS's share price since 2007:

To be fair, quite a lot of RBS has been spun off so it’s a much smaller company than it was in 2008 anyway, but the point still stands that there is no rising trend that we should be riding, as many people seem to think.

The flipside of all this is that Gordon Brown is equally blameless for selling off the government's gold at ‘historically low levels’, except to the extent that we might want the government to own gold for other reasons.

So there is no ‘right time to sell’ except to the extent that we do or do not want the government to own shares in the banks, or to try to make money by taking risks. If we don’t want the government playing the stock market, the ‘right time to sell’ is always now.

Replace the House of Lords with a Lottery

Before the House of Lords Act 1999, foolish legislation from the Commons would often be blocked, delayed or amended by wise men that did not owe anything to anyone and would thus be wise and objective in their decisions. Tony Blair was defeated 38 times in the Commons in his 1st year of government. After 1999 the chamber became nothing more than a useless chamber of former party donors who had been given life peerages often at the request of the Prime Minister. Unsurprisingly they would enter the chamber owing the Prime Minister a favour or two and suddenly a lot of poor legislation is being passed without so much a whimper from that once mighty chamber. While we can all agree the current system is broken, conservatives should recognize the old one is lost, and thus a redesign of the House of Lords should keep the best of the old while discarding some of the more unnecessary inequality of the old system.

My idea is a lottery system, whereby people are, at random, selected to serve as a “Lord” for one Parliamentary session, much like an extended form of Jury service. There would be rules of course- no-one should be forced into it, and those who do accept would have to declare all interests for the purpose of public accountability. To ensure wisdom prevails there should be a minimum age of 45, and anyone who has been closely involved with a political party in the last 5 years should be disqualified. The few hundred who accept will be compensated generously for any time they have missed out of work, and of course because they are all older, this year long task will not take vital time younger people would need in the job market or higher education.

The sheer hassle of such a system will discourage the government from passing excessive legislation to the Lords- and certainly make the legislation understandable for the average laymen who will be serving. The selected group should have the powers the Lords currently have- with the suspensory veto extended from 1 year to 5 years and the formal discarding of the Salisbury Doctrine.

Hopefully this change will result in a conservation of the liberties and property rights Britain still has, and an end to the de facto unicameralism of our current House of Commons.

Theo Cox Dodgson is winner of the Under-18 category of the ASI's 'Young Writer on Liberty' competition. You can follow him on Twitter @theoretical23.

Liberalising Immigration is a Win-Win scenario

Draconian immigration rules represent the largest restriction on liberty in the UK today. They restrict the personal and economic potential of millions of people and achieve little in return. How to roll back these limits on freedom? Think tanks have a difficult dilemma. They want to build a reputation as radical thinkers, but at the same time propose moderate policies. Early drafts of this essay argued that Britain should be more open to this or that group, but the truth is that both hard-headed economics and human decency demand wholesale liberalisation. Immigration restrictions curtail our ability to hire, sell to, befriend and marry the people we want to. People understand this – it's why people view immigration to their local area much more favourably than on the national level. And they have an enormous economic cost.

The ASI's namesake argued that the division of labour is limited by the extent of the market. Everyone accepts the case for free trade, but that leaves markets incomplete, because non-tradable services (like haircuts) can't travel across borders. Freeing people to move where they wish would let people go where their talents would be best used. The productivity of someone with an engineering degree – the amount can achieve with their labour – is many times lower in some areas of the developing world than it is in the UK.

The benefits to migrants are best illustrated by the lengths migrants are willing to go to to cross borders. Smugglers charge thousands for passage from Libya to Europe, and the journey is fraught with risk, but hundreds of thousands make the journey anyway. Migration lets people escape poverty, war and authoritarian regimes.

The Mariel Boatlift is an example of this. In 1980, 125000 Cubans fled Castro's regime, landing in Miami. Their liberation increasing the size of the local labour force by 7% almost overnight. But economists found almost no impact on wages and the labour market.

7% of the UK labour force works out to approximately 2.3m people. The government could auction off permanent residency permits to that many people each year. Such a radical policy would be disruptive. It would have costs, losers as well as winners. But the potential benefits are too colossal to ignore – a Britain where not only workers and jobs but husbands and wives, parents and children, potential pub geezers would not be separated by arbitrary borders.

Theo Clifford is winner of the 18-21 category of the ASI's 'Young Writer on Liberty' competition. You can follow him on @Theo_Clifford, and read his blog at economicsondemand.com.

If you think for profit health care is expensive wait until you see not for profit...

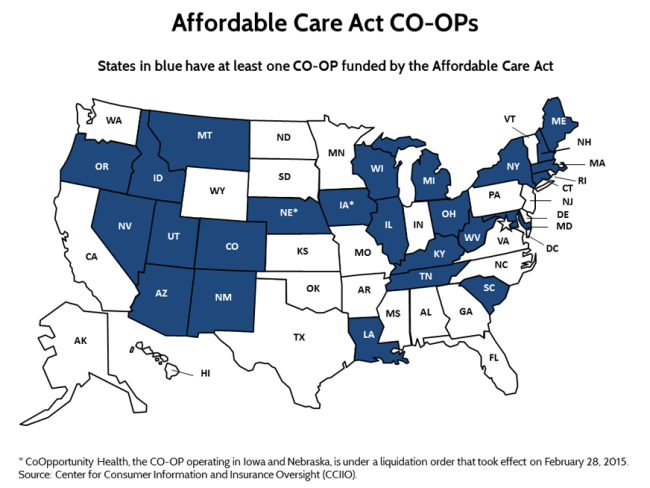

One of the battle cries during the set up of the ACA, aka Obamacare, was that for profit health insurers were way too expensive. Because, you know, profit. It's obvious to all that the profit must make things more expensive, innit? So, a series of cooperatives to provide that health care insurance were set up. There's two problems here. Much as we love cooperatives ourselves the obvious feature of hem is that they've not got any capital. They thus need to grow into a market position rather than just leap into trying to be a large player in a capital hungry industry like insurance. For their capital comes from retained earnings, rather than having some capitalists providing capital: that's rather the point of them. That these coops did try to leap in and become large players in a capital intensive market means they're all going bust.

Nonprofit co-ops, the health care law's public-spirited alternative to mega-insurers, are awash in red ink and many have fallen short of sign-up goals, a government audit has found.

Under President Barack Obama's overhaul, taxpayers provided $2.4 billion in loans to get the co-ops going, but only one out of 23 -- the one in Maine -- made money last year, said the report out Thursday. Another one, the Iowa/Nebraska co-op, was shut down by regulators over financial concerns.

The audit by the Health and Human Services inspector general's office also found that 13 of the 23 lagged far behind their 2014 enrollment projections.

The probe raised concerns about whether federal loans will be repaid, and recommended closer supervision by the administration as well as clear standards for recalling loans if a co-op is no longer viable. Just last week, the Louisiana Health Cooperative announced it would cease offering coverage next year, saying it's "not growing enough to maintain a healthy future." About 16,000 people are covered by that co-op.

Wise observers like Dennis the Peasant were predicting that this would happen. But they're also not cheap:

Separately, the AP used data from the audit to calculate per-enrollee administrative costs for the co-ops in 2014. It ranged from a high of nearly $10,900 per member in Massachusetts to $430 in Kentucky.

Wouldn't everyone prefer a few rapacious capitalists trying to rape the citizenry for profit than admin costs per scheme member of $10,900 a year? Further, can you actually imagine a for profit company allowing bureaucracy to balloon out to such an extent?

Securitising Britain’s Future: A free market solution to university funding

When the Coalition Government increased tuition fees from £3,300 to £9,000 a year, it had done so to provide a sustainable alternative that would boost university’s incomes and cut government spending. But there are reasons to believe this has failed. The Guardian reported that the new funding system is likely to cost the government not less, but more money than the system it replaced. It is time to reevaluate university funding, and I propose the following alternative: a system under which students would agree to ‘sell’ a percentage of their future income to their university in exchange for an education.

Under the current system moral hazard occurs since the universities need not worry about its students’ ability to repay their loans. Instead, the government will bear the costs if students default. This is a problem in desperate need of addressing especially considering that an estimated 73% of graduates will not be able to fully repay their loans.

Under the proposed system in which universities own the income rights to students’ future earnings, the incentive structure would be changed as to align the interests of students, universities and society alike. Universities will factor in how much their education will benefit their students in terms of their future earnings. This allows relative prices to convey how much certain professions are, in fact, valued by society. The university would encourage more students to take up careers that are more valued and it could charge less (in terms of percentage points) for the degrees with better prospects than those with worse.

By contrast, universities today charge uniform rates and have an incentive to provide the most appealing courses - which often mean courses that are enjoyable or easy - rather than being actually useful or valuable. The graduates may therefore lack the skills to be productive members of the workforce, despite accumulating large debts. Universities even have an incentive to admit students it knows will not benefit from the course since it will nonetheless receive government funding.

In turn, universities could sell its future income rights through a process of ‘securitisation’, per course or as a diversified portfolio. This free-market solution provides an equitable opportunity to all, since students’ ability to attend university is not depended upon current wealth but future earnings; thus depended upon skill and merit, not money. This system would streamline all stakeholders’ interests and ‘securitise’ Britain’s free and prosperous future.

Tamay is the runner-up in the 18-21 category of the ASI's 'Young Writer on Liberty' competition.

Devolution and Super-Councils

As Scotland looks set to receive an ‘unprecedented’ collection of powers from Westminster, it is time too for the English regions to benefit from devolution. The lack of what Hayek would call ‘perfect information’ is a weakness intrinsic to a centralised states – surely local councils have a greater understanding of problems that face their local areas than Whitehall? As one of the most centralised states in the world, the UK is ripe for devolution in a variety of policy areas. One such example is taxation. Rather than simply being bankrolled by central government, local authorities should be able to raise their own revenue. This would encourage greater fiscal responsibility from councils, as they would have to justify spending to their electorate, discouraging the waste that has been all too characteristic of local government.

Another possible area of devolution is healthcare: councils should be free to innovate in response to local problems. The savings that this would result in would contribute to the £22 billion of efficiencies in the NHS that Simon Stevens, the Chief Executive of NHS England, has highlighted as necessary by 2020-21. Furthermore, patient satisfaction will improve: the Institute of Economic Affairs has pointed to Switzerland’s decentralised healthcare system, which provides a responsive service with high life expectancy and patient approval ratings.

Having greater powers would also give councils more clout when they bid for major infrastructure projects. London has reaped the fruits of much central government support, with the Greater London Authority securing £4.7 billion from the Department of Transport to fund Crossrail. If all councils had the same bidding powers, government spending would more effectively match the infrastructure needs of the local area – instead of grandiose projects such as HS2, more Crossrails could be built, creating the ‘Northern Powerhouse’ that George Osborne strives for.

How will this devolution create a freer UK? Firstly, councils being forced to raise their own money deters excessive spending, lest councillors be punished by the local electorate who are paying for it. Secondly, healthcare efficiencies mean a smaller burden on the taxpayer to pay for the NHS, while the patient will likely be more satisfied with a service suited for local needs. Finally, this devolution will result in more focussed, efficient infrastructure spending. In short, ‘super-councils’ can reduce the burden on the taxpayer, and create the conditions for a flourishing free market.

Alan Petri is runner-up in the Under-18 category of the ASI's 'Young Writer on Liberty' competition 2015.

Against reform of the House of Lords

This probably won't be all that popular among those who insist that democracy is the be all and end all of a political system. But we think that the current proposals to reform the House of Lords are a bad idea:

Rogue peers should be subject to immediate suspension from the House of Lords when scandals break, a senior Labour peer has said.Lord Soley, a former chairman of the Parliamentary Labour Party, made the call in a letter to Lord Speaker Baroness D'Souza in the wake of the allegations against Lord Sewel.

Well, no. we don't kick an MP out of the House of Commons because a scandal has broken. They do have to leave if they are found guilty of a criminal offence and are then sentenced to more than a minimum amount of jail time. And then there's this:

Peers should be forced to retire when they reach old age to ensure the House of Lords remains "fit for purpose", the Lord Speaker has suggested as she ordered a review into the code of conduct. Writing in The Daily Telegraph, Baroness D'Souza warns reform is “vitally necessary” if the body wants to retain public support in the wake of the Lord Sewel scandal.

Again, no, we are not persuaded.

It's entirely possible to have a very different conversation about whether there should be a House of Lords at all, we should have a unicameral system, one with an elected second house, one selected by sortition, any number of variables. But the real point of a second house at all is to have one that acts as a limit upon the enthusiasms of the mob that directly elected politicians are subject to. And for that limiting to be effective there must be no way to remove those not convicted of some criminal offence of some specific level of gravity. For, given how many things are illegal these days there's absolutely no one who cannot be accused of breaking some law or another. And wouldn't it be remarkable if it were those who were being particularly bloody minded about opposing the executive of the day who were so accused?

After all, at least part of this outrage about Sewel was that he was doing something entirely legal: consorting with ladies of negotiable affection. Something that really is entirely legal in this land, however much it might not be to your or our taste.

Being able to throw peers out because they were a bit doddery, or because a newspaper disapproved of their activities, would greatly weaken the House's ability to be independent of the whims of the passing society. And given that that's what they're there for, to limit the impact of passing fads, we oppose such a change.