So this new technology stuff works then

We’re told that streaming has increased the consumption of music:

The consumption of music in the UK is now higher than in any year since 2006, when the industry was being powered by the downloadable mp3 file. Thirteen years ago, Crazy by Gnarls Barkley became the first song to get to No 1 on downloads alone as consumers switched over from CD singles and filled up iPods with individually purchased tracks (and, possibly, pirated ones too), while still purchasing plenty of CD albums.

Given, as Adam Smith pointed out, that the purpose of all production is consumption this should be welcomed. We all get to consume more music than we did, we’re richer. New technology works therefore, it achieves that goal of increasing our wealth.

There is one little fly in this ointment. Which is that it is conceivable that the turnover of the music business has declined at the same time. Much of this streaming is, after all, available to the consumer for free. This means that GDP will have declined at the same time as we’re all becoming richer.

As many have pointed out there are problems with the manner in which GDP is calculated but this is one that’s given too little weight to our minds. Some at least - we would argue much to all - of the seemingly languid economic growth of the past decade and more is a result of this quirk of how we’re counting.

Our specific example would be WhatsApp. There was a period when it was not charging that $1 a year fee and also was not carrying any advertising. Facebook had a couple of hundred people developing and operating it. Standard GDP calculations included the costs of those engineers and yet applied no value at all to the output or consumption. WhatsApp, in the official way we count these things, therefore turned up in the economic statistics as a decline in global productivity. Which is absurd for a system providing some 1 billion people with some to all of their telecoms needs off the work of 200 people.

Punch an economist hard enough and they’ll agree that this is happening to some extent. We’re outliers here in insisting that much of the modern world can be explained in this manner rather than it being just some fringe issue. But then sometimes outliers are in fact correct….

Truth in advertising - whose truth?

A current insistence is that things said on social media - Facebook, Twitter and the like - must be true. Sometimes this is insisted upon just about commercial advertising, sometimes about political such and, appallingly, at times about any statement whatsoever. The appalling coming from the fact that freedom of speech does indeed include the freedom to be wrong, even to lie.

The problem with this is the same one we’ve got about any declaration of what is the truth - sez ‘oo? As an example:

Facebook has quietly removed false and misleading ads about HIV-prevention medications after months of pressure from LGBTQ+ and health organizations.

Fifty organizations including Glaad and PrEP4All started a public campaign in December, arguing that the social media platform was putting “real people’s lives in imminent danger” by refusing to remove targeted ads containing medically incorrect claims about the side effects of HIV-prevention medications such as Truvada.

The ads highlighted by the campaign were largely run by personal injury lawyers seeking potential clients, and falsely claimed medications like Truvada could cause severe kidney and liver damage.

But “PrEP is safe and generally well-tolerated,” Trevor Hoppe, a sociologist of sexuality, medicine and the law, previously told the Guardian. “Any misinformation to the contrary is likely bad for public health, especially communities hardest hit like gay men in the US.”

That PrEP is generally safe and well tolerated is true. But then so is penicillin and that will still kill some people. Vaccines are generally safe and well tolerated and yet they kill perhaps 1 in a million given them - which is why we have vaccine compensation funds in this country and the US.

Just for the avoidance of doubt we’re all in favour of things like Truvada. People like having sex, the drug reduces the ill effects of their doing so. We like things that reduce the ill effects of what people enjoy doing - statins allow palatable diets into our dotage too, why wouldn’t we be in favour?

But we do get, along with this insistence that we can only handle the truth, this problem of whose truth? For Truvada can indeed cause liver problems:

Truvada can cause serious, life-threatening side effects. These include a buildup of lactic acid in the blood (lactic acidosis) and liver problems.

That’s the US Government and this is the Mayo Clinic:

Two rare but serious reactions to this medicine are lactic acidosis (too much acid in the blood) and liver toxicity, which includes an enlarged liver. These are more common if you are female, very overweight (obese), or have been taking anti-HIV medicines for a long time.

So now the pursuit of truth in advertising leads to the banning of people stating a truth - Truvada can cause liver problems. True, we’re not greatly worried that ambulance chasing lawyers get their business model curbed and yet, actually, we are.

For we come back to this basic point. Who gets to define that truth that is all that can be said - or advertised? The only answer we can come up with which is consistent with maintaining freedom and liberty themselves, let alone freedom of speech, is that no one should have that power because no one is to be trusted with it. As here, activists in favour of the prescribing of Truvada insisting that plain and simple truths may not be stated.

We wouldn’t trust ourselves with that power either - the philosopher kings capable of righteously ordering society simply do not, never have done and never will, exist.

We might even start off the new year with some ancient wisdom - quis custodiet ipsos custodies? For this current idea that what we may say publicly is to be determined by every grouping with a grudge or an agenda is going to mean that we’ll only be allowed to say what is approved of by those with a grudge or agenda.

Rhode Island’s wage and price controls

On December 31st, 1776, Rhode Island introduced wage and price controls. They limited the wages of carpenters to 70 cents a day, and those of tailors to 42 cents a day. These were price ceilings, and it was illegal to set wages or prices higher than the government stipulated levels.

The law fixed maximum prices for items “necessary for existence.” 7s 6d was the maximum for a bushel of wheat, and fourpence-halfpenny a pound for “fresh pork, well-fatted, and of a good quality.” A gallon of New England rum could be sold for no more than 3s 10d, 10d a pound for butter, 8s for a pair of shoes, and 30s for a barrel of blubber.

Other states joined in the “Providence Convention” that sought relief from “the exorbitant prices of goods.” Delegates from Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Connecticut joined those from Rhode Island in recommending maximum wages and prices that were then enacted by state legislatures.

It didn’t work, of course; it never does. Nor did it last; it never does. Within months the ceiling prices were raised, then abandoned. It never works because wages and prices are signals of supply and demand. To fix them by law at arbitrary chosen levels is to deny the ability of supply and demand to determine the levels of wages and prices. It is roughly akin to bunging up a thermometer in an attempt to control temperature.

My colleague, Eamonn Butler, co-authored a book entitled “Forty Centuries of Wage and Price Controls,” detailing every instance in the 4,000 years since Hammurabi of ancient Babylon in which rulers have tried to set wages and prices by law. Many were governed by the false notion that there could be a “just price” for things.

Yet even in Eamonn’s lifetime (and mine), the Heath government in the UK, and the Nixon administration in the US, introduced wage and price controls. They never work, and they didn’t work then, either. They commonly set prices too low to make it worthwhile for producers to bring goods to the market, or set wages too low to make the activity worthwhile. They do not deliver stability, and never have. What they deliver in spades is shortages, and it is the shortages that cause the suffering that eventually makes people rebel against them.

Present day advocates of rent controls should note that they will cause the supply of rental accommodation to disappear, and make it not worthwhile to maintain existing rentals to a high standard. The answer to “exorbitant” prices is to let those prices lure other suppliers into the market in order to profit from them. The increased supply lowers the price more effectively than government laws can.

If Willy Hutton can't get the past right how can he manage the future?

As we all know Willy Hutton has a plan for us all and our society. Which is that it should be managed by people like Willy Hutton. So that we all do what people like Willy think we ought to be doing.

There is a certain problem with this and it’s not just that perhaps we’d prefer not to be doing what we’re told to. The little niggle being that if the planner doesn’t even know what happened in the past then how can they direct that future? Today’s example:

The financial crash of 2008 was the consequence of hyper-deregulation, following the palpably absurd rightwing faith that markets were magic.

The thing being that we didn’t in fact deregulate the financial markets. Far from it in fact. The 1998 Bank of England Act increased the power of the Bank to regulate. Then the 2000 Financial Services Act centralised and strengthened regulatory control again - distinctly stronger regulation than under the 1988 Act.

It’s entirely true that both of these have been superseded by new acts - in 2016 and 2012 respectively - but it’s simply not true that the Blair years brought deregulation of finance let alone hyper- anything.

It is possible that those years brought bad regulation of those markets but that’s rather another matter isn’t it? And one which does rather undermine the idea that the bureaucratic classes - or even Willy Hutton - know what they’re doing and thus should plan matters for us.

Which does lead to that problem about any such set of plans. If the people making them don’t even know what has happened then how can they lay out that future?

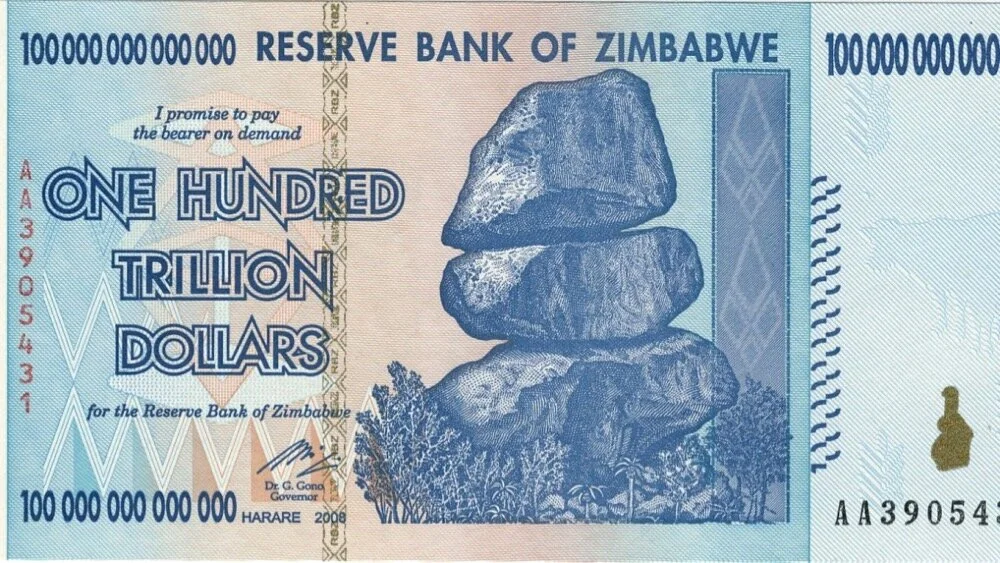

Robert Mugabe’s paper money

Robert Mugabe, who had been a terrorist, became Prime Minister of Zimbabwe in 1980, and on December 30th, 1987, became the country’s President by pushing through a constitutional amendment. The new post made him head of state as well as head of government. He was also commander-in-chief of its armed forces, and could stay on indefinitely as President, and declare martial law and dissolve Parliament if the mood took him.

His policies were disastrous for his country. He favoured his own tribe and stirred up violence against others. He encouraged blacks to seize white-owned farms by violence. Many so seized ceased to produce, and food production declined, causing famines. The economy collapsed. By 2000, living standards were below those when he took office in 1980. Wages were down, and unemployment had rocketed; by 1998 it was almost 50 percent. And by 2009, most of the country’s skilled workforce, some 3-4 million citizens had voted with their feet and emigrated.

Mugabe’s re-election campaigns attracted worldwide derision and condemnation, marked as they were by fraud, ballot-rigging and violence. He was widely condemned for violating human rights and ordering summary execution of opponents. He formed a view that he was the victim of an international gay conspiracy, and pursued a violently anti-gay policy in his own country.

He will be remembered for hyperinflation on a Weimar scale, as well as for his abuse of power. He printed money on a massive scale to finance his activities. An accurate measure is difficult because his government ceased filing statistics at the height of inflation between 2008 and 2009, However, it was estimated that at its peak month it ran at 79.6 billion month on month, and for the year on year in November 2008, it peaked at 89.7 sextillion percent. Eventually the country could no longer afford the ink to print currency with. By then people were using the currency of other countries.

I was given a hundred trillion-dollar banknote which by then would probably not even buy a coffee. There were stories that notices in toilets forbade the use of banknotes instead of toilet paper (they were cheaper). It is an object lesson that never seems to be learned. In a straight line from Weimar through Zimbabwe to Venezuela, excessive printing of money has resulted in hyperinflation and brought savings and investment to a standstill. It is a small irony of history that the same firm that printed the Weimar banknotes also initially oversaw the printing of the Zimbabwe notes.

Adam Smith famously observed that:

“Little else is requisite to carry a state to the highest degree of opulence from the lowest barbarism, but peace, easy taxes, and a tolerable administration of justice.”

He might have added sound money as a further requirement. Zimbabwe under Mugabe had none of these, and its citizens paid the price.

One thing to be grateful to Donald Trump for

We wouldn’t say that we’re greatly enamoured with Donald Trump’s trade policies but there is a silver lining all the same:

Examining his tariff-hiking, trade-war-inducing approach to international relations, their research shows the claim that it protects manufacturing jobs is… fake news. Far from creating jobs, it has reduced them. Yes, domestic manufacturers get some protection within the US market, but that is more than offset by the fact that they face higher costs for components they import and lose export markets when others (such as China and the EU) retaliate. The lesson? Trade wars bad, independent central banks good.

Not just that trying out protectionist policies and thereby proving they don’t work is educational. But the antipathy to Trump is such - all that “Orange Man Bad” stuff all over the place - that anything he proposes is opposed just because of the source of the proposal.

Meaning that the right on left is now near entirely converted to the cause of free trade. Which is indeed a silver lining of great value.

Of course, as soon as the political wheel of fortune turns we’ll find that somehow restrictions upon trade proposed by progressives are different in some manner, miraculously beneficial. But for the moment Trump has managed that impossibility, encouraged the left to embrace a useful economic policy. For which, given the rarity of the event, we should be grateful.

Ronald Coase studied real markets

Ronald Coase, winner of the 1991 Nobel Economics Prize, was born on December 29th, 1910. As is the way of most Nobel economists, he lived a long time, and died in 2013, aged 102. He studied under Arnold Plant at the LSE, and went on to become part of the Chicago School, where he co-edited the influential Journal of Law and Economics.

He gained acclaim by examining why it is that business firms develop as they do, identifying the transaction costs of entering and operating in the market as a key factor determining their size and nature. In a ground-breaking paper, “The Problem of Social Cost,” he dealt with the problems of externalities, and suggested these might be handled by assigning property rights. This approach has been applied to dealing with problems of over-exploiting common resources, such as in the Icelandic fishing industry, where quotas are assigned and traded so that boat-owners have property rights over the fish.

Coase was determined to examine markets that operated in the real world, rather than study theoretical abstract models. It was this empirical approach that led him gradually to alter his political outlook. He started out as a young man thinking of himself as a socialist, but his studies under Plant at the LSE made him recognize the superiority of market systems versus the often ill-conceived government schemes. He studied public utilities in the UK, and working in wartime with the Forestry Commission and the Central Statistical Office, he observed that, “with the country in mortal danger and despite the leadership of Winston Churchill, government departments often seemed more concerned to defend their own interests than those of the country.”

Despite these observations, he still thought of himself as a socialist, but recognized the contradiction, and gradually ceased to describe himself as such as the real world impinged more and more on the theoretical models. He became active postwar in the Mont Pelerin Society founded by F A Hayek.

The Coase journey is one that has been undertaken by many. Starting with a theoretical approach that processes information about an ideal world, setting our models and describing economic activity in terms of equations, some are led to the recognition that this bears sometimes scant relation to the real world in which people do the best they can without perfect knowledge.

It is a commonplace today that many young people’s world view is formed from ideas, and that as they experience more of what actually happens in the world they observe in practice, their views gradually modify to incorporate the lessons of experience. Many come to recognize that it is what actually happens that matters, and that it is sensible, when advocating what a perfect world should be like, to look at what the world is actually like, and at what motivates people in practice. Ronald Coase did, and taught us some valuable economic lessons in consequence.

Clearly, we should all be buying Huawei and writing a thank you note

If other people make things cheaper for us then what is it we should do? The correct response being to then enjoy that greater wealth that those others have enabled us to have. It’s not actually necessary to write a note to Santa as well but perhaps politesse would indicate we should:

The Chinese telecoms company whose role in the construction of Britain’s 5G network has been questioned amid growing security fears has received as much as £57 billion of state aid from Beijing, helping it to expand and undercut its rivals, it is alleged.

A review by The Wall Street Journal of grants, credit facilities, tax breaks and other state assistance shows for the first time the extent to which Huawei has been helped — allegedly enabling it to offer generous financing terms and charge 30 per cent less for network equipment than competitors.

Assume that all of this is true and isn’t just competitors trying to justify their own higher prices - what should our reaction be?

Well, as a result of the Chinese taxpayer being rooked by the Chinese government’s pandering to special interests we can have a 5G telephone network cheaper. Or, presumably, for the same price as we would pay elsewhere we can have more 5G telephone network. Either way we are richer as a result of those taxes paid in China.

The correct response then, to this claim of subsidy of Huawei is to buy Huawei for we’re made richer by doing so. This is true of any such foreign subsidy to a producer as well. The appropriate reaction to such unfair competition is to say thank you, please may I have some more?

That is, foreign subsidy is the same as an advance in production technology, or our useful reaction to trade itself. If, for whatever reason, other people are making us richer then we should enjoy that greater wealth. After all, that is the very thing we’re trying to do, get richer.

Certainly, the Chinese taxpayer has reason to complain but why wouldn’t we appreciate network equipment that is 30% cheaper, wherever the £57 billion to produce it has come from?

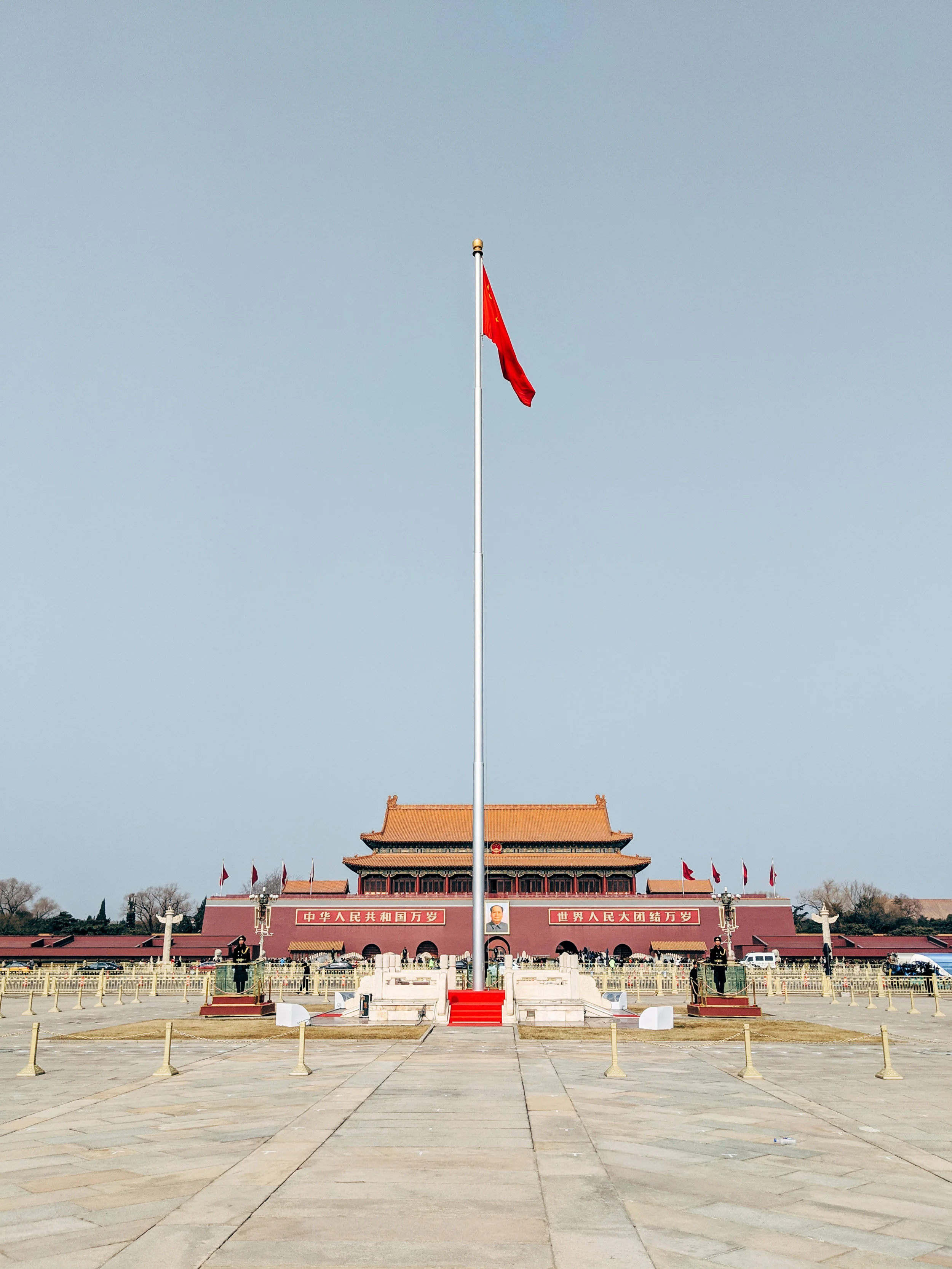

Some will complain that this all makes China richer somehow but that can’t be true. It’s a straight transfer of £57 billion from them to us, from China’s state revenues - thus the Chinese populace - to us consumers. Our only difficulty here is to work out where to send that thank you letter. D’ye think they’d let us post it up on the Tiananmen Gate?

The Gulag Archipelago

On December 28th, 1973, was first published one of the most powerful and influential books of the 20th Century. "The Gulag Archipelago: An Experiment in Literary Investigation" by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn was an account of life in the Soviet forced labour camps, in which Solzhenitsyn himself had been incarcerated. The term GULAG is an acronym for the Russian initials of the Main Directorate of Camps. The camps were like an archipelago of islands, scattered in the vast ocean of Soviet territory, many in the harsh climate of the Siberian wilderness.

Solzhenitsyn's book narrates the history of the forced labour camps from when they were first introduced by Lenin in 1918. He traces through the various purges and show trials that swelled the number of inmates into the millions. Some of it is from his own personal recollections and the interviews he had with other prisoners, many of whom come alive again as they tell their stories in Solzhenitsyn's words. It includes extracts from diaries, personal statements and legal documents, as the picture is built up through independent brush strokes like an Impressionist painting.

It is a devastating story of brutality suffering and injustice, painting a picture of Soviet Communism that taints its memory forever. In one of his anecdotes, Solzhenitsyn tells of the businessman imprisoned because he sat down too early after a 20-minute frenzied standing ovation at the name of Stalin. He tells of a talented young poet who died in a Gulag prison camp, and he writes from memory some of the lines that would never otherwise have seen the light of day.

The story is more moving because it is told simply and factually, an unembroidered account of the monstrous inhumanity the system embodied. Western leftists and Khrushchev himself regarded it as a deviation from communism, but Solzhenitsyn saw it for what it was, an inevitable and systemic outgrowth of the Soviet political programme and culture.

Solzhenitsyn had to write it in secret, hiding manuscripts and typescripts in secret places and with friends. The KGB forced one of his trusted typists to reveal under interrogation the whereabouts of one of the copies, and she hanged herself a few days after they released her. This persuaded him to have it published in the West, instead of in Russia as he had wanted. It was first published in France (in Russian) and circulated clandestinely in Russia.

It was an immediate international sensation. Isaiah Berlin said that until that book, "the Communists and their allies had persuaded their followers that denunciations of the regime were largely bourgeois propaganda." Tom Butler-Bowdon described it as "Solzhenitsyn's monument to the millions tortured and murdered in Soviet Russia between the Bolshevik Revolution and the 1950s." It was the most powerful indictment of a regime ever made. People had known vaguely about Siberian prison camps, but never before had the general reading public been brought face to face with the horrors of the Gulag in such a way.

Early in 1974, Solzhenitsyn was arrested and deported to West Germany. He went via a spell in Switzerland to the United States, where he stayed until the evil empire collapsed, and his citizenship was restored. He returned to Russia, where he died, knowing that he had written what some described as "the book that brought down a system." Those who suffered and who died under that inhuman system live on in the pages of Solzhenitsyn's great book, confronting those who profess communism today not with what it said, but with what it did.

Just what does anyone expect to happen?

The Guardian tells us of the perils of capitalist health care:

'How many more people have to die?': what a closed rural hospital tells us about US healthcare

With the vicious callousness of the capitalist counting his money the hospital was closed, necessitating travel to gain health care.

Dunklin county already has one of the highest post neonatal mortality rates in Missouri. Dr Andrew Beach, one of the few paediatricians left in Kennett, said the entire region of about 70,000 people is now without a full-time obstetrician.

Hmm, well, that “entire region” there is doing a lot of work. For what is actually being faced here is a basic problem of population density. Dunklin County’s population has been falling for near on a century now. It’s definitely smaller than it was in 1950 and the decline doesn’t show any signs of stopping. The county, as opposed to the region, population is now below 30,000.

So what does happen when a population shrinks? The infrastructure supporting it does too. Certain things operate at certain appropriate scales. Hospitals among them.

Take, for example, our own dear NHS, that most definitely not capitalist health care system. Efficient hospital size is taken to be some 200,000 to 300,000 people in the catchment area. Which is why all those small rural hospitals have been closing ever since 1948.

The actual lesson we get from a proper examination of the numbers being that the capitalist lust for profits retained that rural hospital rather longer than the rational planning of socialism would have done.

But then telling the true story wouldn’t have suited The Guardian, would it?