In Defence of Globalisation

Catch up on our latest webinar as Matt Kilcoyne speaks to Cato Intsitute’s Dan Ikenson; Bruno Macaes of Hudson Institute and author of Dawn of Eurasia, Belt and Road, and History has Begun; and Cindy Yu from the Spectator to discuss the era of globalisation, if has come to an end, and what that would mean for all of us.

You can catch up with all the webinars in our series via our webinar section of the website.

That really, really, strong desire to regulate Facebook no matter what

We have the latest entrant in the we must regulate Facebook stakes. Our working assumption is that the insistence upon regulating the site - as with Google and other Big Tech enterprises - is nothing actually to do with whether regulation is necessary or not. They’re simply big organisations and a certain mindset insists that bureaucracies and politics must regulate such. Despite, you know, the inability of bureaucracies and politics to ever create such. Either that or there are an awful lot of bored prodnoses around.

Today’s reason why the regulation is what would happen if the sites failed?

Like banks in the 2008 financial crisis, Facebook and other tech giants are “too big to fail”, according to research from Oxford University that calls for new regulations to protect users, and society, in the event of a possible collapse.

That’s to misunderstand what too big to fail actually means. Which isn’t that the organisation is big enough that we don;t want to see it fail therefore we’ll rescue it if that failure looks likely. Rather, failure would bring the rest of the system down with it which is why we’ll save such organisations. Losing Facebook - their example - would be somewhere between annoying and damaging but it wouldn’t cause the collapse of Google, or Apple, or other social media and certain not the web or the internet. Sure, it’s big and valuable but it’s not systemically important and therefore not too big to fail.

The other mistake in the analysis is this, from the actual paper:

Indeed, the closure of an online social network would not in itself be unprecedented. Over the last two decades, we have seen a number of social networks come and go — including Friendster, Yik Yak and, more recently, Google+ and Yahoo Groups. Others, such as MySpace, continue to languish in a state of decline. Although Facebook is arguably more resilient to the kind of user flight that brought down Friendster (Garcia et al., 2013; Seki and Nakamura, 2016; York and Turcotte, 2015) and MySpace (boyd, 2013), it is not immune to it. These precedents are important for understanding Facebook’s possible decline. Critically, they demonstrate that the closure of Facebook’s main platform does not depend on the exit of all users; Friendster, Google+ and others continued to have users when they were sold or shut down.

Furthermore, as we examine below, any user flight that precedes Facebook’s closure….

Their method of Facebook closing own is that most to all users have already left to go elsewhere. In which case it’s clearly not worth saving because the reason for the failure is that it’s not being used - is not worth saving.

Which rather neatly seems to skewer this justification for regulation of the platform. Not that that will stop people talking it up, For there really are a lot of bored prodnoses out there - or perhaps people who just cannot live with the idea that voluntary cooperation can be left to get on with itself without the oversight of bureaucracies or politicians.

Sir Michael Marmot is becoming a one hit wonder

Michael Marmot is here again to tell us all that it’s the rise in inequality which has caused the coronavirus deaths in the UK. There are a number of problems with his diagnosis:

The political mood of the decade from 2010 was one of the rolling back of the state, and a continuation of an apparent consensus that things were best left to the market. At times, this aversion to government action was made worse by a suspicion of expertise.

This rolling back of the state was seen clearly in a reduction in public spending from 42% of GDP in 2009-10 to 35% in 2018-19.

That’s actually so misleading as to be tantamount to casuistry. The rolling back of the state? Tax as a percentage of GDP was higher, at 33.5%, in 2018 than it was in 2007 - 33%. Public spending as a percentage of GDP was 40% in 2018 as against 39.6% in 2007. We are at least starting from before the Crash to after it, while Marmot is - deliberately we fear - starting from the Crash induced Keynesian expansion of public spending as a percentage of GDP. Largely driven by GDP falling, the entire place becoming poorer.

Oh, and inequality, measured by the Gini, is lower today (and in 2018) than in 2007. There hasn’t been a shrinkage in government as a portion of everything, there hasn’t been a rise in inequality. Which does rather leave the idea that we’re all dying like flies as a result of a reduction in government and an increase in inequality rather lacking empirical support.

Of course, it’s possible to put forward all sorts of ideas as to why the Covid-19 death rate is worse here. Possible ideas are the inadequacy of the government provided health care system. Or, possibly relevant to a disease known to be spread via droplets, the fact that Britain’s insane planning permission system leads to the smallest new houses in Europe. But those are mere ideas, we’d not try to insist upon either of them without actual evidence in favour of them - and a useful lack of evidence contradicting them.

But then we’re not professors of epidemiology so perhaps this insistence upon evidence isn’t quite the way to do it?

Can vaping reduce inequality?

Covid-19 has affected different groups in different ways and thrust the issue of health inequality into public debate. Whilst people are mistakenly concerned with inequality itself, there are good reasons to make it as easy as possible for those with worse health outcomes to lead healthier lives by expanding choice. This doesn’t have to come from top down state control or regulation, which is often unsuccessful, but can be driven by invention and the market.

In England those in the least deprived parts live, on average, 19 more years in good health than people in the most deprived areas. Some would jump for the easiest explanation, perhaps discrimination. However, the true causes are myriad and complex, but one thing that is clear is that those same groups with worse health outcomes are also more likely to smoke. ONS data suggests those earning below £10,000 per year smoke at double the rate to those earning above £40,000. Smoking is also expensive due to the high and regressive tax placed on the product. This further leads to a reduction in the money in the pocket of Britain's poorest: something confirmed by a 2019 University College London study which found that smokers could save around £780 a year by vaping instead. Vaping is therefore a win-win for both the health and income of Britain's poorest.

Despite the huge efforts from public health lobbies and vast amounts of taxpayer funding spent on cessation services, the most successful method for stopping smoking is vaping. A recent study found that smokers were able to abstain from smoking using vaping at nearly double the rate of those that used nicotine patches.

Ultimately, Britain's poorest have the most to gain from the innovations that are taking place in the new world of nicotine. But across the world, the freedom of individuals to vape is coming under attack: from Australia where vaping is effectively banned, to the Netherlands where a counterproductive ban on flavours is planned for 2021. The liberty for individuals to choose to improve their health by vaping is being constricted. The European Union is even considering taxing the product. Britain has largely been a force for good in promoting a harm reduction approach, with much of the world looking on at our ever-reducing smoking population with envy. However, these changes have not come about because of government mandates, but instead due to vaping technology being developed and sold by entrepreneurs.

This wave of innovation is not over. Entrepreneurs and businesses have developed other lower-risk nicotine products which may entice those that haven't chosen to switch to vaping. Swedish Snus (which to the EU's shame was banned in the 1990s) continues to save lives in Sweden where they have the EU’s lowest cancer rate in men due to its use as a safer alternative to smoking. Perhaps now we have left the EU and are free to make our laws the Government may decide to legalise its sale. Already though inventors have circumvented the ban on snus and introduced tobacco-free alternatives called nicotine pouches.

Inventors have also found ways to heat tobacco but avoid the dangerous combustion, therefore delivering nicotine to the user without many of the harmful health effects. One such product has recently been authorised by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to be advertised in America as a modified risk product. The ability to inform the public about health risks is important because currently a large proportion of UK smokers and ex-smokers overestimate the relative harmfulness of e-cigarettes: misattributing smoking harms to nicotine rather than the combustion of cigarettes. A film to be released this year aims to try and combat these misconceptions.

The British Government has set an ambitious plan to be smoke-free by 2030. But the truth is that unless the Government stops preventing firms and individuals spreading the message about these reduced risk nicotine products then we will miss the target by some margin. It is frankly not good enough for the Government to do nothing on this issue, it actually needs to get out of the way.

Mark Oates is a Fellow at the Adam Smith Institute, as well as the Director of We Vape and the Snus Users Association.

This may or may not happen

The Financial Times tells us - well, the FT quotes someone as saying that - inflation might be a’comin’:

US faces inflation threat as money supply rockets

This is one of those things that may or may not happen - after all we’ve all been trying to create inflation this past decade and some countries have been more successful than others.

It is true though that M0, 1 and 2 are wildly expanded as a result of QE and Ms 3 and 4 not so much. If those latter two respond - or return to responding - as theory predicts they should to the first three then there is indeed a massive bolus of inflation in the system. They might, of course, not do so given that they haven’t in these recent years - this is just part of the economic circumstance in which we find ourselves.

All of which is going to be most interesting as it will test this Modern Monetary Theory to destruction. If massive money printing does lead to that inflation then there are only two solutions. One is to reverse QE - thus massive money printing isn’t something possible to continue. The other is to raise taxes which rather obviates the point of MMT itself. For it would mean a return to that dualism of high spending meaning, by necessity, high taxes. There is no free lunch that is.

What fun that an economic theory gains this real world test so soon after its formulation. The advantage being that we’ll be able to put it back to bed pretty soon - for we are really pretty certain that inflation is out there. Other episodes of the same thing by a different name - monetisation of fiscal policy - have tended to work out that way from Diocletian onwards.

We don't, in fact, care about the producers

On the subject of Spotify we’re told that:

I pay for Spotify, so I am part of the problem. I know that £9.99 a month for access to almost all music, ever, is a steal.

The problem apparently being that the pop stars, the ones producing the songs, aren’t now making country GDP sized incomes from having done so. This is not a problem.

Our aim in having an economy - a civilisation even - is that we, the people out here, consumers get more of whatever it is that we desire. So, the modern music industry is a steal for consumers, that’s the point of it all.

As far as producers are concerned we’re only interested in their incomes in so far as they’re still sufficient for them to continue to produce the item. If they do then they obviously think the deal is fair enough for if they didn’t they’d be off claiming their furlough payments from Starbucks.

All the music of the ages is now available for a pittance? To complain of this is like whingeing about how cheap printing has become allowing all to read as much as they wish. It’s also to miss the point of the system, that our aim is to do this to everything. To, as Marx insisted would happen, use capitalism to conquer the problem of economic scarcity. Only every other sector of the economy to do this to and true communism can finally arrive.

They're still not understanding the economics of planning reform

Well, yes, this is rather the point:

In one fell swoop, the entire system that has governed land use in England for more than 70 years has been set ablaze.

Who knew that progressive liberals were such conservatives that something should be kept just because it has existed?

As with Polly Toynbee yesterday though they’re still not grasping the economics of the matter:

Luckily however, in 2018 the government commissioned an independent review to identify the drivers of slow construction rates in England. The so-called Letwin review found that the main bottleneck on housing supply isn’t the planning system, but the “market absorption rate” – the rate at which newly constructed homes can be sold on the local market without materially disturbing the existing market price.

In a system where development is left in the hands of profit-maximising firms, there is a strong incentive to build strategic land banks and drip-feed new homes on to the market at a slow rate. The reason for this is simple: releasing too many homes at once would reduce house prices in the area, which in turn would reduce profits.

By handing over even more power to private developers, the government’s reforms will make this problem even worse.

Let’s imagine that everything up until the last sentence is in fact correct. So, how do we solve this? Producers can only control the total amount of whatever it is that is placed upon the market if there is some monopoly or powerful oligopoly in the system. In a free market you cannot restrict supply in order to maintain price. For if you do the other folks in the market won’t.

So, if a third or a half of the country can now be built upon how can anyone restrict housebuilding so as to maintain prices? They can’t - which is one of the points of the reform itself. And if they try then others won’t thereby defeating the tactic anyway.

Once again we’ve people complaining about their specific worry being solved. Perhaps it would help if those who wished to do economic planning understood some economics?

To complain about the problem you're complaining about being solved

We expect this sort of behaviour from a politician or bureaucracy of course for if a problem is actually solved then there’s no more need for political oversight - interference we mean - nor the existence of the bureaucracy. But we would rather expect one of the country’s senior journalists to be able to do better than this:

Developers are the booming winners in this stagnant decade, sitting on land-banks for a million homes, their executives rewarded in multiple millions.

....

Any remaining local control is dismissed as nimbyism, though records show that 90% of local planning permissions are granted.

It also takes an average of five years to go from empty land to building starting such is the length of that planning process.

Building completions are running at around - we’ve rounded the number just to make the maths easier - 200,000 a year.

It’s reasonable, actually in business terms we say this is the minimum requirement for being sensible, to have in stock whatever it is to cover you until it is possible to get some more. If steel takes 3 months from order to delivery then having 3 months of steel on hand is sensible. If land to build upon takes 5 years to get then a sensible - again, note, this is a minimum requirement - idea to have a five year supply to hand. If building is 200k a year and it takes 5 years to gain more plots then 1 million will be the stock at hand.

if the new planning system shortens that process then the land banks will diminish. Polly Toynbee - for of course it is her - is complaining about the solution to the very problem she is identifying. Not just to be contrary, but because she doesn’t understand the subject under discussion.

We wish we could be surprised at that last sentence.

We've been waiting for this other shoe to drop

Many of us working in NHS hospitals welcomed the news earlier this week that the government had purchased 90-minute Covid-19 tests. Rapid swab tests, called LamPORE, and 5,000 machines, supplied by DnaNudge, will soon be available in adult care settings and laboratories. If they’re effective, they could allow for rapid, on-the-spot testing. But there’s no publicly available data about the accuracy of these tests or how they perform, raising concerns about why the government has endorsed – and purchased - them.

Think back a couple of months. Then the cry was that tests - any tests - should be used in vast numbers. Government just needs to get out there and buy them. Given this insistence before any particularly valid tests actually existed there was obviously going to be some spraying of money at tests which don’t actually work.

No, we do not say that these specific tests do or don’t. Just that in any such system of payment for development there is going to be payment for developments that don’t pan out.

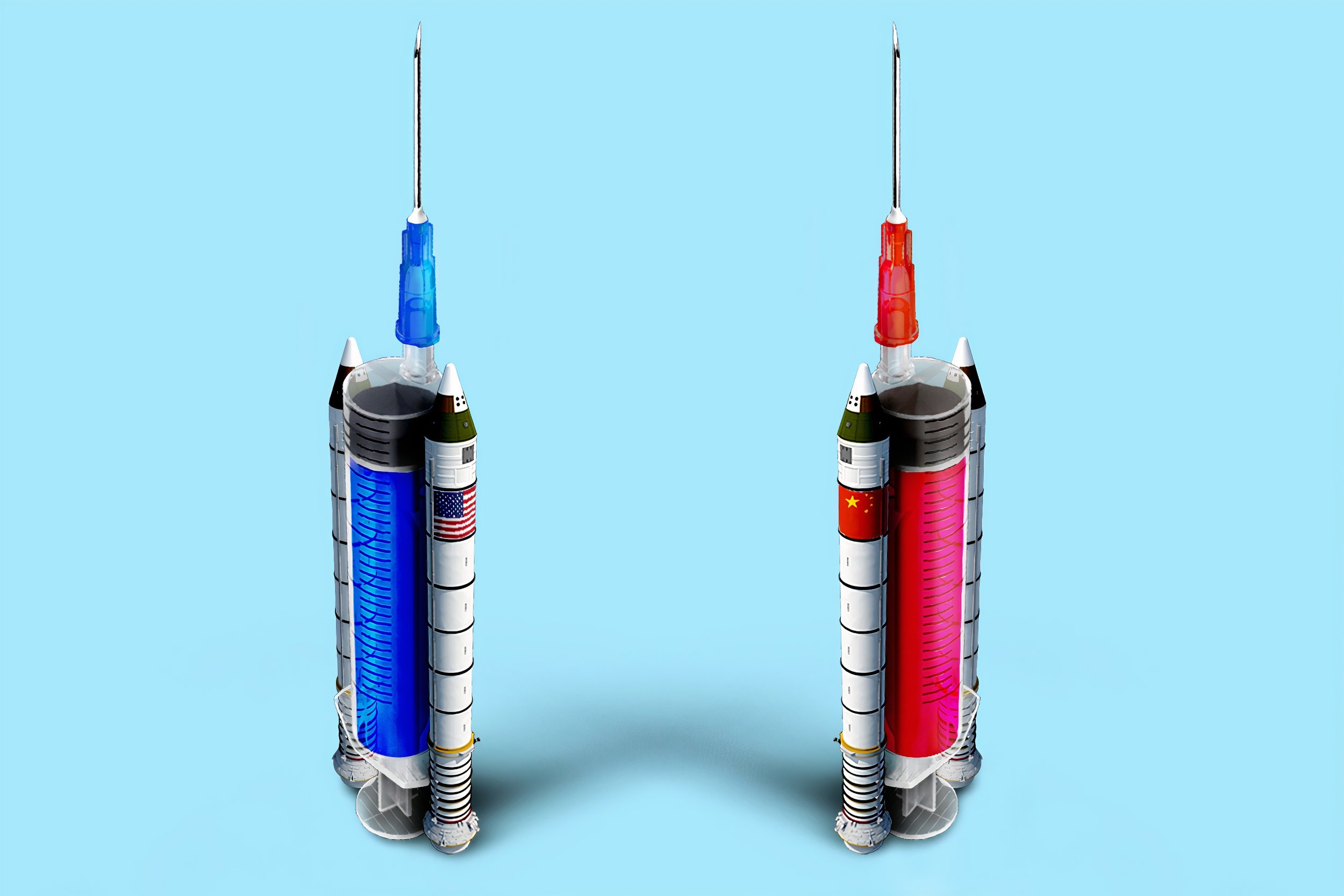

This also being a larger issue. For pledges are being made to purchase millions of doses of this vaccine, tens of millions of that. None of which have been proven to work as yet. The purchases being across the spectrum of those that might work - which means again there are going to be significant purchases of vaccines that don’t. Or less well than others, certainly government is going to end up buying what is not used. Which will call forth the same wailin’ an’ a cryin’ that these tests are.

However, look on the bright side. It will bring into the public conversation just how expensive drug development is - as opposed to the usual complaints about how high the profits are. For in that usual complaint about capitalist drug development the comparison is made between the amount one company has invested in a drug and the amount of money received from having done so. Which isn’t the correct comparison at all. Rather, it’s all the money that was invested in searching for a drug as against the revenues from the one that succeeded.

Now, with government paying all those costs of all developments we’re going to see this, vividly, how much it really does cost. And yes, large amounts of what is spent is indeed wasted. The thing being that in the old system it’s the capitalists who risk - and waste - their money, in this new world of government drug development it’s us taxpayers. There’s even the possibility that with the costs being made so evident that those who argue fort the nationalisation of drug development will end up having to wind their necks in.

We can hope at least. Drug development is an inherently wasteful and therefore expensive endeavour. It’s probably cheaper to leave it to the capitalists to do then only spend taxpayer's’ money on the winner.

To introduce The Guardian to a little economics

The Guardian has been telling us for a couple of decades now that Britain really must get out of this low wage, low productivity, employment and production system that we have. They might even be right for as Paul Krugman has pointed out productivity isn’t everything but in the long run it’s almost everything.

It is necessary - OK, desirable then - that the paper also know how the economic thigh bone is linked to the economic hip bone. What they desire is happening right now and they’re complaining about it:

Firms cut jobs amid recovery worries

UK service sector companies cut jobs at a sharper pace in July, because they are worried that the Covid-19 recovery will be slow.

So says Duncan Brock, Group Director at the Chartered Institute of Procurement & Supply. He warns that there are still serious ‘underlying problems’ in the economy, even though activity grew last month.

From the source, the PMIs:

UK service providers reported a strong increase in business activity during July, with the rate of growth the sharpest recorded for five years. New orders also rebounded during the latest survey period, reflecting an improvement in corporate and household spending. Growth was mainly linked to the phased reopening of business operations across the UK economy. Employment was a weak point in July, with staffing numbers falling at a steep and accelerated pace ...

That is rising productivity. We need to use less labour to produce the same amount. Or less labour to produce more in this case. That’s the very definition of the rising productivity which it is said we should desire and work towards.

There is that necessary connection - rising productivity means fewer jobs in what we do now.