Yes, it's trivial, but that's the point

We would note that we’re not averse to some form of licencing for muskets and the like. And yet:

Members of the UK’s leading Napoleonic re-enactment society have said post-Brexit customs rules fail to account for their firearms, leaving them at risk of having their weapons confiscated.

The Napoleonic Association is meant to be heading to the central Spanish-Portuguese border this week for a re-enactment of the 1810 Siege of Almeida.

But they fear they might have to wield pitchforks as Portuguese peasants instead of being British soldiers armed with muskets and rifles.

Before Brexit, re-enactors could obtain a free European licence alongside their shotgun licence, which is used for old-fashioned long arms, allowing them to travel freely with their weapons.

However, the activity is so niche that no provisions seem to exist for it under post-Brexit customs systems.

This is trivial in one sense - now that the issue has been brought to public attention no doubt some alleviation of the problem will take place. However, it does illustrate the problem with a fine grained regulatory state. The bureaucracy never is going to think of everything now, is it? And yet - the clue being in that “fine grained” idea - a bureaucracy which tries to insist on a rule for everything has to think of everything in order to have a rule for it.

This is merely annoying when there are some thousands who already do the thing to be regulated. Eventually, at least, the rule will be issued in a manner that allows the thing to be done. But what happens with new things that are as yet undone, but which that fine grained state insists must have a rule? There is no constituency to push for the rule, nor for the rule to be sensible.

The biggest problem with regulation isn’t that it stops us doing current things for there’s a political constituency to allow them to continue. The problem is the stopping of doing new things because, by definition, there’s no constituency extant to insist that the bureaucracy stop being so damn silly.

That there are already Napoleonic re-enactors means that a solution will be found. But if there were not, and someone were thinking of starting, then how would the rule that allowed it come into being?

Not knowing current reality makes planning very difficult

Hayek - of course - pointed out that the centre just never can know the economy in the level of detail required to be able to plan it. The collection of the necessary data, its processing, just isn’t possible. That’s before we get to how said centre isn’t going to be able to predict the future with any certainty.

Ah, but what if we devolve it all to the experts? That’ll work, right? Except that doesn’t either, as any one plan suffers from the same failures. What’s required is that multiplicity of plans which then offers options under changing circumstances.

Also, it has to be said that some acclaimed experts are not, in fact, such. As here:

I worked for BP for 30 years – the energy sector has become incompetent and greedy

Nick Butler

Strong claim. More expertise claimed:

Nick Butler is a visiting professor at King’s College London, and a former group vice-president for strategy and policy development at BP, and an adviser to Gordon Brown

Well, pass on that planning job then, we are saved!

Except, except:

The third challenge beyond the freeze is to secure adequate physical supplies of gas. This is a matter for close cooperation between the government and the energy sector. Other European countries, led by Germany, have been actively seeking resources on the world market to replace the supplies no longer coming from Russia. The EU has created a single-buyer mechanism and individual countries are pursuing new deals with producers around the world, from Qatar and Algeria to the US. Spare resources are scarce because investment levels have been low and new supplies typically take three to five years to come onstream. The result is that a physical shortage of gas across the EU is highly likely this winter.

Yes, a great deal of truth in that.

Germany and others are preparing for that risk with serious plans for rationing consumption. The UK, apparently considering itself immune to Europe’s problems, has done nothing and is not even matching the current voluntary measures being adopted across the EU to reduce consumption. Ministers seem not to realise that if countries such as France and Norway limit supplies to the UK this winter in order to meet their own needs, the shortages could be real and substantial. The urgent need is to secure a buffer of additional supplies and develop the long-neglected gas storage facilities that other countries take for granted. Securing and maintaining adequate supplies requires a public-private partnership with the common, overriding aim of maintaining energy security.

And that’s grossly ill-informed, even ignorant. Which is not a good look in a would-be planner.

Those supplies from Qatar, Algeria and the US? They’ll be liquefied natural gas. Which requires a very specific - and expensive - port facility to be able to land. An LNG decompression plant being something that Germany has none of - not a one. In fact the gas pipelines to the Continent are now stuffed full of LNG derived natural gas which is landed in the UK - from Qatar, Algeria, the US etc - decompressed in UK LNG landing plants and sent off to our confreres.

Far from having done nothing the UK has done the one thing that would alleviate those gas shortages - built the infrastructure to allow the world’s LNG supplies to be landed in Europe. Through, err, private companies and without a national plan to boot.

As we’ve remarked before there are problems with national planning as an economic structure. Hayek’s knowledge problem being one of them - that knowledge that would be planners don’t seem to have.

Not knowing current reality makes planning very difficult.

Should'a gone fracking to beat fuel poverty

The Guardian tells us that the nation will be plunged into fuel poverty:

Two-thirds of all UK households will be trapped in fuel poverty by January with planned government support leaving even middle-income households struggling to pay their bills, according to research.

It shows 18 million families, the equivalent of 45 million people, will be left trying to make ends meet after further predicted rises in the energy price cap in October and January.

An estimated 86.4% of pensioner couples are expected to fall into fuel poverty, traditionally defined as when energy costs exceed 10% of a household’s net income, and 90.4% of lone parents with two or more children.

We do like that “traditionally” there. For the definition of fuel poverty is something rather new. The level of heating that is meant is vastly above what was normal even in the lifetimes of us old folk here. Efficient central heating only became a British commonplace in the 1980s after all. That the common even middle class experience of the 1970s as regards heating is now regarded as poverty is a sign of how far we’ve come. We all expect those linen shirts today as it were. To bludgeon the point, that you are defined as poor today for not having what only the rich used to have - a heated whole house - is evidence of considerable advance in living standards.

But it’s also interesting to ponder how we should - should have perhaps - deal with this. Ryan Bourne tells us that the carbon tax is the way to go. Indeed so, for what that does is operate as a filter on things that should be done and things that shouldn’t.

The economist William Nordhaus laid out the basics of climate change economics in a speech to accept his 2018 Nobel prize. Carbon emissions generate an “externality”, he explained, as households and firms consuming or producing carbon do not account for the social costs of global warming. The best response, he said, would be to estimate these global costs and account for them by adding a uniform carbon price to reflect the damage of all incremental emissions. We could call it “a carbon tax”.

The Stern Review says much the same thing. Take that Stern valuation of those externalities - $80 a tonne CO2. Call that, between friends and at current exchange rates, €80 a tonne.

Ireland’s tax is €7.41 per MWhr of natural gas at a tax rate of some €40 per tonne CO2. So double that to gain the Stern rate - €15 per MWhr. The European price of gas is currently €226 per MWhr.

The point about the tax is to put the costs into prices. If, having paid those costs, the activity is still value additive then we should go ahead and do it. For our task is to maximise human utility over time. All those dastardly things we do to the future are in that tax. The benefits of doing it are here and now. The tax also stops us doing the things that are not value additive, which detract from human utility over time.

So, would fracking for natural gas produce fuel which would be value additive? The other way of putting this is could fracked gas carry a tax of €15 per MWhr and still be value additive at a market price of €226 per MWhr? The answer is obviously and clearly yes. Therefore we should have gone fracking for gas, still should go fracking for gas.

Of course, the truly evil thing we’ve done here is agree with every single one of the assumptions made by the climate change crowd and still proven that fracking is the right thing to be doing. They’ll not forgive us for that, obviously. But it is true all the same.

The science of climate change says that we should be fracking for gas. However much anyone wants to deny it ‘tis true.

Sewage overflow numbers are not quite what you might think - or are being told

This is particularly shocking:

Sewage spills by water firms have risen 29-fold over the past five years, official data reveals.

The number of times raw sewage has been dumped into rivers and lakes across the country has risen from 12,637 in 2016 to 372,533 last year, according to the Environment Agency.

Shocking because, as presented, it’s simply not believable. The water system has become 29 times worse in just the past 5 years? No, really, it hasn’t. That just doesn’t pass the smell test.

A growing population as well as heavier and more frequent storms has led to excessive amounts of sewage getting dumped into other water sources, according to the Department for Food and Rural Affairs (Defra).

Sure, that might have an effect but it would be pretty marginal. Not x29.

….part of the increase shown in the figures is down to better monitoring from water companies over time.

Ah, what part though?

Which brings us to this:

The Environment Agency (EA) and Ofwat have launched a major investigation into sewage treatment works, after new checks led to water companies admitting that they could be releasing unpermitted sewage discharges into rivers and watercourses.

New checks, is it?

In recent years the EA and Ofwat have been pushing water companies to improve their day-to-day performance and meet progressively higher standards to protect the environment.

As part of this, the EA has been checking that water companies comply with requirements and has asked them to fit new monitors at sewage treatment works.

Higher standards and more monitors, is it?

At which point what is really happening becomes clearer. More monitoring of sewage overflows is happening - therefore more sewage overflows are being found.

This all leaves entirely open what is the correct number of such overflows to be having. So too the cost of not having them. Even, is the state owned water system in Scotland doing better or worse by this same measure? Are they, in fact, measuring the same thing in the same way?

But those larger questions can be put aside for a moment or two. The x29 increase in detected sewage overflows is a result of more detectoring of sewage overflows going on - not some catastrophic change in the performance of the sewage system.

Think on it - if the system goes looking for more overflows under tighter standards of what constitutes an overflow then more overflows are going to be found, aren’t they? Which does mean that a claim about an increase in overflows happening, rather than an increase in overflows being detected, is more than a little mendacious.

Henry Dimbleby is entirely missing the point

Apparently we must do this and that and all because:

The only way to have sustainable land use in this country, and avoid ecological breakdown, is to vastly reduce consumption of meat and dairy, according to the UK government’s food tsar.

Henry Dimbleby told the Guardian that although asking the public to eat less meat – supported by a mix of incentives and penalties – would be politically toxic, it was the only way to meet the country’s climate and biodiversity targets.

“It’s an incredibly inefficient use of land to grow crops, feed them to a ruminant or pig or chicken which then over its lifecycle converts them into a very small amount of protein for us to eat,” he said.

Except this is to entirely miss the point of the task. Our aim is to maximise human utility over time. Utility is something defined by the person doing the consumption.

Yes, of course, there are third party effects and those need to be considered. But so too does the utility - that’s what is damaged by the third party effects either way. Either by an action causing that decline in utility, or the consumers’ decline in utility by not performing the action. It’s the balance that matters - the optimal position which maximises utility within the constraints the universe sets upon us.

Once the correct logical basis is established it’s possible to see what’s wrong with Dimbleby’s pronouncements. He’s forgotten that people like to eat meat. Therefore there’s a trade off in that utility. To be more extreme than he is, a fully vegan world would have lost that pleasure of meat eating, that’s a cost to be set against whatever effect that would have upon climate change.

If plans are made without even understanding what the goal is then they’re going to be bad plans, aren’t they?

Of course, we can go further too - there’s no reason whatsoever that the land of England needs to feed England. We do have this thing called trade which can aid in that. Missing out that little factor moves this all from a bad plan to a grossly stupid one. But then as the Stern Review itself said, we just musn’t try to plan our way out of climate change because every idiot with an obsession will come out of the woodwork (we might have changed the language there a little bit). Instead change prices the once and then leave markets to optimise utility - you know, the thing markets are good at?

Introduce School Choice to Save Children with SENs

Earlier this year, the children’s commissioner Rachel de Souza released her report into England’s ‘missing children’- those who have fallen through the gaps of our education system. Unfortunately, the number of these missing children have soared in the wake of the pandemic, with pupils with SEN among those being let down in England’s schools.

In fact, children with SENs or an Education Healthcare Plan (EHC) have a persistent absence rate that is more than double those without an identified SEN. Two years of disrupted learning has only exacerbated this issue, with SEN children being disproportionately affected by the lockdown.

It is, then, welcome news that the Government has acknowledged that things need to change. Education Secretary Nadhim Zahawi announced plans to train 5,000 more early-years teachers to be SEN co-ordinators, aiming to:

“…give confidence to families across the country that from very early on in their child's journey through education, whatever their level of need, their local school will be equipped to offer a tailored and high-quality level of support”.

But throwing more taxpayer money at a centralised education system—one that restricts families in the choices that they make—is ineffectual. The current “one-size-fits-all” model assumes that every child learns in the same way, meaning that children with SENs are not adequately taught.

By contrast, giving parents greater choice over where they send their children would encourage greater specialisation in learning techniques, meaning that education would truly become “tailored and high-quality”. A system of school vouchers through a public-private partnership would ensure that every family in the UK could choose for themselves where, and by extension, how, their children are educated.

Under such a system, the government would allocate a voucher to families, so that they are free to make the decision on where to send their children themselves. Parents would then have the option to top-up these vouchers if they deem this to be financially feasible, giving them the freedom to choose how their child is educated, whilst also ensuring that no one goes without an education.

School vouchers are not a novel idea- they are based on Milton Friedman’s arguments for greater freedom of choice, as he set out in his classic 1962 book “Capitalism and Freedom”. A number of these market oriented reforms have been implemented based on Friedman’s fundamental belief that governments should fund schools, but not administer them.

This school voucher system would give families greater freedom of choice. This means scrapping the current “one-size-fits-all” model, which does not cater to anyone’s learning needs adequately, and is an especially poor system for those with SENs. Parents know their children’s learning needs the best, and so a system of educational freedom would allow families to make educational choices specific to their child.

It also opens up the education market, allowing for schools to specialise in particular learning methods and styles. Just as a blanket insurance plan would not cater to every insurance need, and individual consumers choose insurance plans based on their specific needs, families should have the freedom to choose what works for them. A voucher system hands parents the power to demand what works for their child.

Furthermore, a voucher system means that teachers are directly accountable to parents, giving schools strong incentives to meet the needs of their students. Just like any other consumer, an unsatisfied family can take their voucher money elsewhere. If a child with SEN is not being adequately taught at one school, families are able to simply move to another. This puts competitive pressure on schools, increasing the overall quality of education. Research has shown that student performance in both Milwaukee and Florida improved following the launch of school choice opportunities for this reason.

Competition drives up both quality and choice: education is no exception.

Addressing the Right Problem

Last month, in a somewhat bizarre throw-back to the 2010 General Election, Suella Braverman diagnosed one of the causes of Britain’s current woes; “There are too many people in this country of working age, who are of good health and also are choosing to rely on benefits.”

She is missing the central point. Britain is indeed on the verge of entering another recession, but unlike the 2008 down-turn, it is not one—at least yet—that is underlined by a high unemployment rate. In 2011, the unemployment rate reached a peak of 8.5%. In comparison, the UK’s unemployment rate currently sits at 3.8%, while the economic inactivity rate has also been in decline. Indeed, the Department for Work & Pensions has spent the last few months gleefully sending out press releases announcing how many more people they have helped into work.

Source: Office for National Statistics

This rhetorical appeal to ‘work-shy Britain’ also omits the fact that 40% of people on Universal Credit (UC) are employed, whilst 1.4 million people are claiming working tax credit. The cost of living crisis isn’t a symptom of a high unemployment rate; it is shining a harsh light onto the problem of in-work poverty.

When I talk about poverty, I do not mean ‘relative poverty,’ which is often how it is defined. Those living in relative poverty live in a household which has an income below 60% of the inflation-adjusted median income of a base year (usually 2010/2011.) Of far more use are more measures such as the Joseph Rowntree Foundation’s conception of a minimum income standard, which is an annual calculation of the cost of items and activities we deem to be necessary for an acceptable standard of living in the UK. This is analogous to Adam Smith’s own conception of poverty in his Wealth of Nations:

“A linen shirt, for example, is, strictly speaking, not a necessity of life. The Greeks and Romans lived, I suppose, very comfortably though they had no linen. But in the present times, through the greater part of Europe, a creditable day-labourer would be ashamed to appear in public without a linen shirt.”

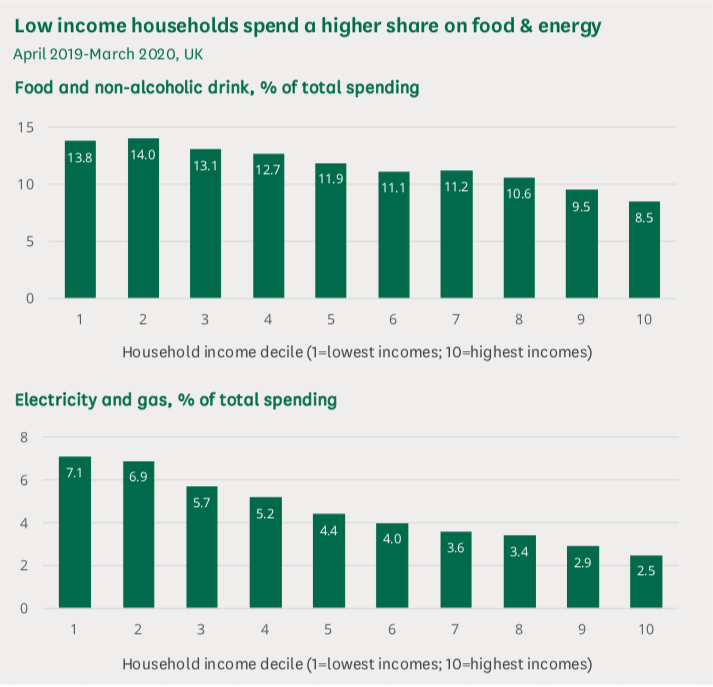

The inability of many people in work to afford items we would consider essential is precisely the problem; the price of food and energy are the top two reasons behind UK adults reporting an increase in their cost of living. Unsurprisingly, lower-income households are the most affected by rising prices as they spend a larger proportion of their income on energy and food. Worse still, lower-income households are facing inflation rates around 1.5 percentage points higher than higher-income households due to rising energy prices.

Source: House of Commons Library

Unfortunately, there are no immediate fixes. But there are a few reforms that the Government could enact to reduce in-work poverty. Firstly, it could help to reduce some of the higher costs facing workers through enacting supply-side reforms. This would include reforming our hideously outdated planning laws in order to drive down house prices, and relaxing child:staff ratios to reduce childcare costs.

Secondly, it could reduce the tax burden on workers. One simple way of doing this would be to index tax brackets, in particular the Personal Allowance, to inflation in order to eliminate fiscal drag.

Thirdly, it could seriously consider introducing a system of Negative Income Tax, (NIT), which would act as a minimum income guarantee, tapering away as peoples’ wages rose through work.

Fourthly, it could stimulate an increase in productivity, which is linked to workers’ wages, through replacing the super-deduction policy, thereby incentivising greater investment in capital. At present, the UK is forecast to be the slowest-growing economy in the G7 by 2023—if the Government is serious about wanting the UK to be a high-wage economy, this is something that needs addressing.

The outlook for those on lower wages over the next couple of months is bleak. The Conservative Party will not do itself, nor the public, any favours by complaining that Britons simply ‘aren’t working’ and reproaching a ‘culture of dependency’ which they have served to entrench through failing to enact necessary reforms for economic growth, rather than accurately diagnosing the problem.

What you measure, and how, is the essence of any sort of planning

Yet it’s not obvious that those who would plan actually understand this:

In 2018, a report by the TUC revealed that private and public investment as a proportion of national income put us 34th in a ranking of 36, trailed only by Portugal and Greece. In the 40 years to 2019, fixed investment in the UK averaged 19% of GDP, the lowest in the G7. Now, business investment in the UK remains more than 9% below its pre-pandemic level. Crucial parts of our national infrastructure have been failed twice over: first when they were state-owned and let down by the stinginess of the man from the ministry – and then when they became privatised victims of modern capitalism’s increasing fondness for stripping out, squeezing down, and chasing dividends.

Well, yeeees. Part of the TUC’s case there is that because we in Britain have a smaller manufacturing sector than many other countries therefore we invest less in manufacturing. Which seems entirely logical.

We might also ponder that investment is a cost. Therefore decrying the low levels of investment could be seen as complaining about how low our costs are.

However, there’s a deeper problem here, one of simple measurement. Or perhaps complex measurement. If we are to decide to plan, which is the insistence here, then we’ve got to understand the data that we’re trying to plan from. After all, it’s only that understanding that turns data into information. And the truth is that there’s a distinct lack of understanding of that data here.

The definition of investment is, in fact, non-current spending. For the GDP numbers - which all of this is drawn from - that becomes that spending which is accounted for across accounting time periods. Current spending is that which is accounted for as spending in this, the current, accounting period. Investment is that which is written off over more than the one accounting period. The inverse of this same statement is that investment is whatever it is that we depreciate, current spending is what we do not. We can get more complex than this but that is the essence of it in the national accounts.

That switch from manufacturing to services - the thing which we’ve done more than most nations - has an effect upon this. Because an awful lot of what could be called “investment” in services is in fact written off in the one accounting period. Very few firms capitalise their software development these days, just as one example. Those costs are - usually you understand - accounted for as current expenses in the wages of the developers, not something that is then depreciated across time.

This then goes further. This distinction causes other national accounts problems too. The old way of buying in software was to buy a license - that was a capital investment which then was written down, depreciated over time. The new way is to rent by the month - Software as a Service, or SaaS. That’s a current expense, not an investment. And as the developing firm is also accounting for the software development costs as a current expense - mostly to often enough - we seem to have a fall in investment within the economy. Switching from Office, on a 2 year licence, to Office 365, on a monthly rental, reduces investment in the national accounts even as exactly the same activity, by the same people, in the same place, happens.

This might all sound a little recondite and it is. It’s also not the full explanation but it is at least a part of it. The national accounts were drawn up in a different age, measure the world of that previous time. They don’t deal well, the definitions, with our modern world. They are, therefore, not all that useful as a base to plan the future from. Because they’re not telling us what most think they are.

If, just to pick an example, Trotters Independent Traders switches from a purchased copy of Sage to a monthly subscription to Sage then investment as classified in the national accounts falls. This does mean that looking at the levels of investment in the national accounts is not a good guide to the current state of the economy and is thus a very bad base from which to try to plan the future.

Just and only the public cloud part of SaaS amounts to some 0.5% of GDP.

Of course, Hayek said all of this rather more carefully but it is still true. The centre doesn’t have the information necessary to do the planning so many people want the centre to do. Therefore that planning from the centre isn’t going to work.

It's astonishing how little Willy Hutton knows

Given that it always takes more time to clean up intellectual ordure than to create it to concentrate on just the one point here from Willy Hutton:

As British exports stagnate, there is not a nod to the role of trade as a propellant of growth. The UK, as the second largest exporter of services in the world – built on intangibles that sit behind sectors as diverse as finance and the creative industries – is locked out of the country’s largest markets in Europe. It is a growth plan built on sand.

British finance locked out of its largest markets in Europe?

London remains the world’s second-biggest financial center behind New York when infrastructure, reputation and business environment are taken into account, according to the Global Financial Centres Index 2021.

Well, that’s a disastrous result. So is this:

The London Stock Exchange's LCH unit in London clears about 90% of euro interest rate derivatives, a contract widely used by companies in the EU to insure themselves against unexpected moves in borrowing costs.

We can even go further from that same source:

The European Union agreed on Tuesday to prolong until June 30, 2025 permission for Britain's clearing houses to continue serving customers in the bloc, with officials saying it would be the final extension.

Why has the EU done so? Because 90% of the business is in London, that’s why. What we’ve got here is an extreme and clear example of the usual and general truth. The people who benefit from a service are the people who buy it, not those who provide it. That’s why they buy it, see? London finances business in the EU. The EU - and the businesses in it - benefit from that financing. As to why it’s all in London, the EU’s own evaluation is:

The place of London as a major financial centre largely predates the single market and relies on a dynamic business environment, the predictability of the British legal system, the worldwide use of English as language for business, and the attractiveness of a cosmopolitan city.

It’s not about trade barriers nor being inside them. In fact, London has often benefitted from being well outside regulatory systems - the Eurobond market is proof of that.

We do not pretend that everything is rosy in this financial garden but it’s also true that the old, apocryphal, headline applies here - “Fog in Channel, Continent Cut Off”. This being something the EU recognises. The City, those London based wholesale financial markets, is not locked out of its largest markets. Entirely the opposite.

Now “someone is wrong on the internet” is not really a reason to stay up at night. But it is worth pointing out how Willy Hutton is an exemplar of that more general point. Those who would plan our lives, the economy, the country, always do seem to be those with the least knowledge of how it all currently works. Which isn’t, when you think of it, all that good a method of deciding what to do next. For if you’ve no clue where you currently are then how can you decide a path to any destination?

It's necessary to understand that corporation tax is a bad tax

All taxes make the wallet of some live human being lighter. There is no exception to this rule. The study of whose, when, is that of tax incidence.

The incidence of corporation tax is split between the shareholders and all the workers in the economy where the tax applies. For if you tax the return to capital then you will have reduced the return to capital thereby reducing the amount of capital invested. Since it is capital added to labour which increases labour productivity this then reduces the growth of wages - average wages are determined by average labour productivity.

All of this is well known. Where disagreements come in is what is that split between capital and labour? It is absolutely not the corporation that pays - that might be a legal person but it’s not a live human being therefore it cannot carry the economic burden of the tax. Reasonable studies of the US state that it’s 70/30 capital to labour in that market. Other, equally reasonable, studies indicate 30/70. A study here argues 50/50 for the UK.

One study by Kimberly Clausing argues that it’s 0% the workers. Although when directly questioned when that came out (by this writer asking the question of her) Professor Clausing did agree that the result could be driven by multinational companies already using offshore to reduce their tax bills, severely limiting the relevance of the result.

We also know what drives the split. The smaller the economy in relation to the global one, the more mobile the capital under discussion, the more it will be the workers carrying the burden. It was also a result from Tony Atkinson and Joe Stiglitz that the burden could be more than 100%. That is, the workers could lose in wages more than the amount raised in tax - although we’d expect that result to apply in small and poor countries where the capital under discussion is foreign investment.

This loss from this form of taxation is known as the deadweight cost. What is lost purely from the amount of tax raised, the method of doing so. This is nothing at all to do with hte good that may be gained from the spending of the money, it’s purely a commentary on how the tax is raised, how much is, from whom.

We have a spectrum of rising deadweights too. From repeated taxation of real property (so, an LVT, the taxation of resource rents and so on) through consumption taxes (VAT say), to income taxes, to capital and corporation taxes. Topping out at vastly the most expensive in this sense are transactions taxes (the Robin Hood tax on financial markets say).

So, corporation tax is a bad tax because it has high deadweights - we lose more economic activity this way than by raising the same revenue from less damaging taxes. This birden also falls ever more heavily the smaller a place is, the poorer it is. In developing countries the damage is more than the revenue raised.

All of which is a prelude to this:

Liz Truss could pull the UK out of a deal agreed by Rishi Sunak to “stitch-up” global corporation tax rates at 15 per cent, it has emerged, as two of her most prominent supporters criticised the agreement.

That attempt at the minimum is an international cartel determined to enforce a bad tax. Of course we should pull out of it. Even if not for ourselves then for those in the developing countries where it bites hardest.

As to why the attempt at the cartel that’s because almost no one outside the actual experts in the field of taxation understands the first 8 paragraphs of this little note. Therefore politicians see it as a convenient way of taxing them over there, those corporations, to provide nice things for voters. Instead of what it is, a method of impoverishing those same voters.

Competition between nations to lower the corporation tax rate is exactly what stops that political pillaging. Which is why the politicians are so against that competition.