The TUC is being very silly about the £15 minimum wage

The TUC has decided to call for a £15 minimum wage. We assume that it’s all because the Americans have had that Fight for $15. The TUC seeming not to know that $15 is a different sum from £15.

More importantly, $15 an hour in a country where the median wage is $30 (-ish) is very different from £15 where the median wage is £13.57. That second is moving into Lake Woebegon territory, where all our children are above average.

Yes, this is important:

Inevitably, the TUC’s proposal will prompt warnings that higher pay will come at the expense of jobs. But this argument has been deployed ever since Tony Blair’s government introduced the minimum wage in 1999 at £3.60 an hour. The massive job losses predicted then have not happened and there has been no trade off between tackling poverty pay and employment.

In large part, that is because increases in the minimum wage have been gradual over the past quarter of a century. The Low Pay Commission, the tripartite body that recommends the level at which the minimum wage should be set, has continued to push the boundaries to see how high the wage can go without any deleterious effects. Its conclusion is: so far, so good.

Actually, the Low Pay Commission report on the effects of the minimum wage said that it cost some 30,000 jobs at that original and low level. As ever in economics the point is not that some of this will happen, it’s how much of this will at what price? A minimum wage of £1 an hour in an economy of £13 wages has a trivial effect simply because near no one is paid £1 an hour in such an economy. A £50 an hour minimum will have a large effect. What we want to know is how much effect at what price?

Fortunately the government commissioned a report on just this point. Arindrajit Dube is a very pro-minimum wage researcher so it’s not like us, or the New York Times, shouting that the only real minimum is £0 an hour (true by the way, for that’s what you get if you’ve no job). Dube’s specific task was to look at what portion of the median wage can that minimum be pushed up to without startlingly bad effects elsewhere?

The answer is in that 50 to 60% range of the median. Not a huge surprise really, as that result can be seen in work from back in the 1950s too. Not that many people get paid much less than 50% of the median wage so the effects of pushing the minimum up to that are there, they most certainly are, but they’re not large. The effects fall on the disabled, the young and untrained, we would and do argue that those costs are too high. But the more general effects of shafting large numbers of workers through unemployment arrive in that 50 - 60% of median range.

Sajid Javid at one point announced a policy of getting the minimum to 66% of median. This being pure politics - 66% of median is the normal definition of “low pay” so pushing the min up to that level of med. would allow one to crow that “I’ve abolished low pay!”. Except, of course, for all those on £0 as a result.

One more thing. We talked (OK, emailed) directly with Professor Dube when his report came out. There are two median wages we can use. There’s the full time, full year median, which is some £15.65. There’s the all workers - so including part time and part year - of £13.57. Which of these does that 50-60% range refer to?

Sadly for those who would like a much higher minimum wage it’s the lower of those two. Even if we accept all of the assumptions being made about the minimum wage. We don’t care about the young, untrained or disabled, we’re OK with there being some unemployment effects but not too many, then the maximum sensible minimum wage for the UK is £8.14 an hour.

The TUC’s decided that £15 looks much better on the basis of a comparison with a different country, with a different wage structure, in a different currency. But Fight for £15’s a good campaign slogan.

Have we mentioned before why we think that politics is a bad way to run an economy?

There's a certain rub to this plan

Not the specific plan for semiconductors, but the plan to have a plan about a business sector such as semiconductors:

Smarter, more precise policy can benefit our own chip industry much more, as would being mindful of the Chinese acquiring vital IP for peanuts.

Smarter policy would be a benefit, of course it would. But that runs into a problem. How do we gain smarter policy?

Biden’s Chips Act overwhelmingly favours the big SoCs, which very much reflects the lobbying behind it.

Any policy which depends upon politics for either design or implementation is going to be subject to political lobbying. Which is why such a plan will reflect the weight of political power in any particular direction. Not, in fact, what is sensible or smart to do about the problem under discussion.

This next part should probably be read to the sound of massed ranks of own trumpet blowing. But one of us here is one of the half dozen or so global experts on one of the rare earths. Used to deal with more than 50% of the global market in fact. The British government has a critical minerals policy it has been working on for some time - which does indeed include the rare earths. That expert here at the ASI has even written a whole book on the subject. And yet in that multi-year process of devising that national plan on the subject where this global expert could offer some insight there’s been not the one single contact from those devising the plan. It’s not as if they’d have to look far - we are, after all, only a couple of hundred yards from Whitehall.

Yes, there’s an element of “But why didn’t they ask us? Aren’t we important or famous enough?” here for those who would like to impute such. And yet it is something of a failure all the same. If we had been asked our advice would have been to spend a couple of million on certain basic research, not the many millions on subsidising a factory using old technology but that’s almost by the by. A planning process that doesn’t use expertise available on the doorstep is a less than exhaustive planning process, isn’t it?

Or, as we might also put it. Planning through the political process ends up being those elected because they’re good at kissing babies doing whatever they’re told by those who shout loudest at them. This isn’t a good way of building plans - nor of running the country.

The argument for minarchy is watching what governments do

We’ve said often enough that if we assume that what is said about climate change is entirely true then the policies to deal with it are still wrong. We’re confident in that because the Stern Review, the Nobel Laureate William Nordhaus and the vast, vast, majority of other economists all tell us that the policy decisions are wrong. Don’t try and be clever and plan everything, make the one single change to the price system and leave the market be to work it out from there. The carbon tax that is - not what all governments are actually doing instead.

One example of which is Drax:

Mike Childs, head of research at Friends of the Earth, said: “For over a decade the Government has known that in some circumstances burning biomass to make electricity can be worse than burning gas or coal.

“Yet they failed to set strict enough standards on what can be burnt and where it comes from.

"Instead, Drax has received billions of pounds worth of public subsidies."

Commissioned by the Department of Energy, the 2014 report looked at the carbon intensity of burning wood for power.

It found that using forest “residues” for fuel was less carbon-intensive than burning gas and coal over a period of 100 years, but that using whole trees was worse than burning coal when measured over 40 years and 100 years.

Add in the emissions from transport from North America and it’s a complete failure as a policy. But it’s subsidised to the tune of near a billion a year. Which is, even at the interface of government and the energy business, real money.

From which we derive our more general case. The argument for having less government, for minarchy, is watching what governments do. That also means that we’ve a corollary to Occam’s Razor - Adam’s Shaving Brush perhaps. The solution which involves less government is less likely to be counterproductive.

Yes, it's trivial, but that's the point

We would note that we’re not averse to some form of licencing for muskets and the like. And yet:

Members of the UK’s leading Napoleonic re-enactment society have said post-Brexit customs rules fail to account for their firearms, leaving them at risk of having their weapons confiscated.

The Napoleonic Association is meant to be heading to the central Spanish-Portuguese border this week for a re-enactment of the 1810 Siege of Almeida.

But they fear they might have to wield pitchforks as Portuguese peasants instead of being British soldiers armed with muskets and rifles.

Before Brexit, re-enactors could obtain a free European licence alongside their shotgun licence, which is used for old-fashioned long arms, allowing them to travel freely with their weapons.

However, the activity is so niche that no provisions seem to exist for it under post-Brexit customs systems.

This is trivial in one sense - now that the issue has been brought to public attention no doubt some alleviation of the problem will take place. However, it does illustrate the problem with a fine grained regulatory state. The bureaucracy never is going to think of everything now, is it? And yet - the clue being in that “fine grained” idea - a bureaucracy which tries to insist on a rule for everything has to think of everything in order to have a rule for it.

This is merely annoying when there are some thousands who already do the thing to be regulated. Eventually, at least, the rule will be issued in a manner that allows the thing to be done. But what happens with new things that are as yet undone, but which that fine grained state insists must have a rule? There is no constituency to push for the rule, nor for the rule to be sensible.

The biggest problem with regulation isn’t that it stops us doing current things for there’s a political constituency to allow them to continue. The problem is the stopping of doing new things because, by definition, there’s no constituency extant to insist that the bureaucracy stop being so damn silly.

That there are already Napoleonic re-enactors means that a solution will be found. But if there were not, and someone were thinking of starting, then how would the rule that allowed it come into being?

Not knowing current reality makes planning very difficult

Hayek - of course - pointed out that the centre just never can know the economy in the level of detail required to be able to plan it. The collection of the necessary data, its processing, just isn’t possible. That’s before we get to how said centre isn’t going to be able to predict the future with any certainty.

Ah, but what if we devolve it all to the experts? That’ll work, right? Except that doesn’t either, as any one plan suffers from the same failures. What’s required is that multiplicity of plans which then offers options under changing circumstances.

Also, it has to be said that some acclaimed experts are not, in fact, such. As here:

I worked for BP for 30 years – the energy sector has become incompetent and greedy

Nick Butler

Strong claim. More expertise claimed:

Nick Butler is a visiting professor at King’s College London, and a former group vice-president for strategy and policy development at BP, and an adviser to Gordon Brown

Well, pass on that planning job then, we are saved!

Except, except:

The third challenge beyond the freeze is to secure adequate physical supplies of gas. This is a matter for close cooperation between the government and the energy sector. Other European countries, led by Germany, have been actively seeking resources on the world market to replace the supplies no longer coming from Russia. The EU has created a single-buyer mechanism and individual countries are pursuing new deals with producers around the world, from Qatar and Algeria to the US. Spare resources are scarce because investment levels have been low and new supplies typically take three to five years to come onstream. The result is that a physical shortage of gas across the EU is highly likely this winter.

Yes, a great deal of truth in that.

Germany and others are preparing for that risk with serious plans for rationing consumption. The UK, apparently considering itself immune to Europe’s problems, has done nothing and is not even matching the current voluntary measures being adopted across the EU to reduce consumption. Ministers seem not to realise that if countries such as France and Norway limit supplies to the UK this winter in order to meet their own needs, the shortages could be real and substantial. The urgent need is to secure a buffer of additional supplies and develop the long-neglected gas storage facilities that other countries take for granted. Securing and maintaining adequate supplies requires a public-private partnership with the common, overriding aim of maintaining energy security.

And that’s grossly ill-informed, even ignorant. Which is not a good look in a would-be planner.

Those supplies from Qatar, Algeria and the US? They’ll be liquefied natural gas. Which requires a very specific - and expensive - port facility to be able to land. An LNG decompression plant being something that Germany has none of - not a one. In fact the gas pipelines to the Continent are now stuffed full of LNG derived natural gas which is landed in the UK - from Qatar, Algeria, the US etc - decompressed in UK LNG landing plants and sent off to our confreres.

Far from having done nothing the UK has done the one thing that would alleviate those gas shortages - built the infrastructure to allow the world’s LNG supplies to be landed in Europe. Through, err, private companies and without a national plan to boot.

As we’ve remarked before there are problems with national planning as an economic structure. Hayek’s knowledge problem being one of them - that knowledge that would be planners don’t seem to have.

Not knowing current reality makes planning very difficult.

Should'a gone fracking to beat fuel poverty

The Guardian tells us that the nation will be plunged into fuel poverty:

Two-thirds of all UK households will be trapped in fuel poverty by January with planned government support leaving even middle-income households struggling to pay their bills, according to research.

It shows 18 million families, the equivalent of 45 million people, will be left trying to make ends meet after further predicted rises in the energy price cap in October and January.

An estimated 86.4% of pensioner couples are expected to fall into fuel poverty, traditionally defined as when energy costs exceed 10% of a household’s net income, and 90.4% of lone parents with two or more children.

We do like that “traditionally” there. For the definition of fuel poverty is something rather new. The level of heating that is meant is vastly above what was normal even in the lifetimes of us old folk here. Efficient central heating only became a British commonplace in the 1980s after all. That the common even middle class experience of the 1970s as regards heating is now regarded as poverty is a sign of how far we’ve come. We all expect those linen shirts today as it were. To bludgeon the point, that you are defined as poor today for not having what only the rich used to have - a heated whole house - is evidence of considerable advance in living standards.

But it’s also interesting to ponder how we should - should have perhaps - deal with this. Ryan Bourne tells us that the carbon tax is the way to go. Indeed so, for what that does is operate as a filter on things that should be done and things that shouldn’t.

The economist William Nordhaus laid out the basics of climate change economics in a speech to accept his 2018 Nobel prize. Carbon emissions generate an “externality”, he explained, as households and firms consuming or producing carbon do not account for the social costs of global warming. The best response, he said, would be to estimate these global costs and account for them by adding a uniform carbon price to reflect the damage of all incremental emissions. We could call it “a carbon tax”.

The Stern Review says much the same thing. Take that Stern valuation of those externalities - $80 a tonne CO2. Call that, between friends and at current exchange rates, €80 a tonne.

Ireland’s tax is €7.41 per MWhr of natural gas at a tax rate of some €40 per tonne CO2. So double that to gain the Stern rate - €15 per MWhr. The European price of gas is currently €226 per MWhr.

The point about the tax is to put the costs into prices. If, having paid those costs, the activity is still value additive then we should go ahead and do it. For our task is to maximise human utility over time. All those dastardly things we do to the future are in that tax. The benefits of doing it are here and now. The tax also stops us doing the things that are not value additive, which detract from human utility over time.

So, would fracking for natural gas produce fuel which would be value additive? The other way of putting this is could fracked gas carry a tax of €15 per MWhr and still be value additive at a market price of €226 per MWhr? The answer is obviously and clearly yes. Therefore we should have gone fracking for gas, still should go fracking for gas.

Of course, the truly evil thing we’ve done here is agree with every single one of the assumptions made by the climate change crowd and still proven that fracking is the right thing to be doing. They’ll not forgive us for that, obviously. But it is true all the same.

The science of climate change says that we should be fracking for gas. However much anyone wants to deny it ‘tis true.

Sewage overflow numbers are not quite what you might think - or are being told

This is particularly shocking:

Sewage spills by water firms have risen 29-fold over the past five years, official data reveals.

The number of times raw sewage has been dumped into rivers and lakes across the country has risen from 12,637 in 2016 to 372,533 last year, according to the Environment Agency.

Shocking because, as presented, it’s simply not believable. The water system has become 29 times worse in just the past 5 years? No, really, it hasn’t. That just doesn’t pass the smell test.

A growing population as well as heavier and more frequent storms has led to excessive amounts of sewage getting dumped into other water sources, according to the Department for Food and Rural Affairs (Defra).

Sure, that might have an effect but it would be pretty marginal. Not x29.

….part of the increase shown in the figures is down to better monitoring from water companies over time.

Ah, what part though?

Which brings us to this:

The Environment Agency (EA) and Ofwat have launched a major investigation into sewage treatment works, after new checks led to water companies admitting that they could be releasing unpermitted sewage discharges into rivers and watercourses.

New checks, is it?

In recent years the EA and Ofwat have been pushing water companies to improve their day-to-day performance and meet progressively higher standards to protect the environment.

As part of this, the EA has been checking that water companies comply with requirements and has asked them to fit new monitors at sewage treatment works.

Higher standards and more monitors, is it?

At which point what is really happening becomes clearer. More monitoring of sewage overflows is happening - therefore more sewage overflows are being found.

This all leaves entirely open what is the correct number of such overflows to be having. So too the cost of not having them. Even, is the state owned water system in Scotland doing better or worse by this same measure? Are they, in fact, measuring the same thing in the same way?

But those larger questions can be put aside for a moment or two. The x29 increase in detected sewage overflows is a result of more detectoring of sewage overflows going on - not some catastrophic change in the performance of the sewage system.

Think on it - if the system goes looking for more overflows under tighter standards of what constitutes an overflow then more overflows are going to be found, aren’t they? Which does mean that a claim about an increase in overflows happening, rather than an increase in overflows being detected, is more than a little mendacious.

Henry Dimbleby is entirely missing the point

Apparently we must do this and that and all because:

The only way to have sustainable land use in this country, and avoid ecological breakdown, is to vastly reduce consumption of meat and dairy, according to the UK government’s food tsar.

Henry Dimbleby told the Guardian that although asking the public to eat less meat – supported by a mix of incentives and penalties – would be politically toxic, it was the only way to meet the country’s climate and biodiversity targets.

“It’s an incredibly inefficient use of land to grow crops, feed them to a ruminant or pig or chicken which then over its lifecycle converts them into a very small amount of protein for us to eat,” he said.

Except this is to entirely miss the point of the task. Our aim is to maximise human utility over time. Utility is something defined by the person doing the consumption.

Yes, of course, there are third party effects and those need to be considered. But so too does the utility - that’s what is damaged by the third party effects either way. Either by an action causing that decline in utility, or the consumers’ decline in utility by not performing the action. It’s the balance that matters - the optimal position which maximises utility within the constraints the universe sets upon us.

Once the correct logical basis is established it’s possible to see what’s wrong with Dimbleby’s pronouncements. He’s forgotten that people like to eat meat. Therefore there’s a trade off in that utility. To be more extreme than he is, a fully vegan world would have lost that pleasure of meat eating, that’s a cost to be set against whatever effect that would have upon climate change.

If plans are made without even understanding what the goal is then they’re going to be bad plans, aren’t they?

Of course, we can go further too - there’s no reason whatsoever that the land of England needs to feed England. We do have this thing called trade which can aid in that. Missing out that little factor moves this all from a bad plan to a grossly stupid one. But then as the Stern Review itself said, we just musn’t try to plan our way out of climate change because every idiot with an obsession will come out of the woodwork (we might have changed the language there a little bit). Instead change prices the once and then leave markets to optimise utility - you know, the thing markets are good at?

Introduce School Choice to Save Children with SENs

Earlier this year, the children’s commissioner Rachel de Souza released her report into England’s ‘missing children’- those who have fallen through the gaps of our education system. Unfortunately, the number of these missing children have soared in the wake of the pandemic, with pupils with SEN among those being let down in England’s schools.

In fact, children with SENs or an Education Healthcare Plan (EHC) have a persistent absence rate that is more than double those without an identified SEN. Two years of disrupted learning has only exacerbated this issue, with SEN children being disproportionately affected by the lockdown.

It is, then, welcome news that the Government has acknowledged that things need to change. Education Secretary Nadhim Zahawi announced plans to train 5,000 more early-years teachers to be SEN co-ordinators, aiming to:

“…give confidence to families across the country that from very early on in their child's journey through education, whatever their level of need, their local school will be equipped to offer a tailored and high-quality level of support”.

But throwing more taxpayer money at a centralised education system—one that restricts families in the choices that they make—is ineffectual. The current “one-size-fits-all” model assumes that every child learns in the same way, meaning that children with SENs are not adequately taught.

By contrast, giving parents greater choice over where they send their children would encourage greater specialisation in learning techniques, meaning that education would truly become “tailored and high-quality”. A system of school vouchers through a public-private partnership would ensure that every family in the UK could choose for themselves where, and by extension, how, their children are educated.

Under such a system, the government would allocate a voucher to families, so that they are free to make the decision on where to send their children themselves. Parents would then have the option to top-up these vouchers if they deem this to be financially feasible, giving them the freedom to choose how their child is educated, whilst also ensuring that no one goes without an education.

School vouchers are not a novel idea- they are based on Milton Friedman’s arguments for greater freedom of choice, as he set out in his classic 1962 book “Capitalism and Freedom”. A number of these market oriented reforms have been implemented based on Friedman’s fundamental belief that governments should fund schools, but not administer them.

This school voucher system would give families greater freedom of choice. This means scrapping the current “one-size-fits-all” model, which does not cater to anyone’s learning needs adequately, and is an especially poor system for those with SENs. Parents know their children’s learning needs the best, and so a system of educational freedom would allow families to make educational choices specific to their child.

It also opens up the education market, allowing for schools to specialise in particular learning methods and styles. Just as a blanket insurance plan would not cater to every insurance need, and individual consumers choose insurance plans based on their specific needs, families should have the freedom to choose what works for them. A voucher system hands parents the power to demand what works for their child.

Furthermore, a voucher system means that teachers are directly accountable to parents, giving schools strong incentives to meet the needs of their students. Just like any other consumer, an unsatisfied family can take their voucher money elsewhere. If a child with SEN is not being adequately taught at one school, families are able to simply move to another. This puts competitive pressure on schools, increasing the overall quality of education. Research has shown that student performance in both Milwaukee and Florida improved following the launch of school choice opportunities for this reason.

Competition drives up both quality and choice: education is no exception.

Addressing the Right Problem

Last month, in a somewhat bizarre throw-back to the 2010 General Election, Suella Braverman diagnosed one of the causes of Britain’s current woes; “There are too many people in this country of working age, who are of good health and also are choosing to rely on benefits.”

She is missing the central point. Britain is indeed on the verge of entering another recession, but unlike the 2008 down-turn, it is not one—at least yet—that is underlined by a high unemployment rate. In 2011, the unemployment rate reached a peak of 8.5%. In comparison, the UK’s unemployment rate currently sits at 3.8%, while the economic inactivity rate has also been in decline. Indeed, the Department for Work & Pensions has spent the last few months gleefully sending out press releases announcing how many more people they have helped into work.

Source: Office for National Statistics

This rhetorical appeal to ‘work-shy Britain’ also omits the fact that 40% of people on Universal Credit (UC) are employed, whilst 1.4 million people are claiming working tax credit. The cost of living crisis isn’t a symptom of a high unemployment rate; it is shining a harsh light onto the problem of in-work poverty.

When I talk about poverty, I do not mean ‘relative poverty,’ which is often how it is defined. Those living in relative poverty live in a household which has an income below 60% of the inflation-adjusted median income of a base year (usually 2010/2011.) Of far more use are more measures such as the Joseph Rowntree Foundation’s conception of a minimum income standard, which is an annual calculation of the cost of items and activities we deem to be necessary for an acceptable standard of living in the UK. This is analogous to Adam Smith’s own conception of poverty in his Wealth of Nations:

“A linen shirt, for example, is, strictly speaking, not a necessity of life. The Greeks and Romans lived, I suppose, very comfortably though they had no linen. But in the present times, through the greater part of Europe, a creditable day-labourer would be ashamed to appear in public without a linen shirt.”

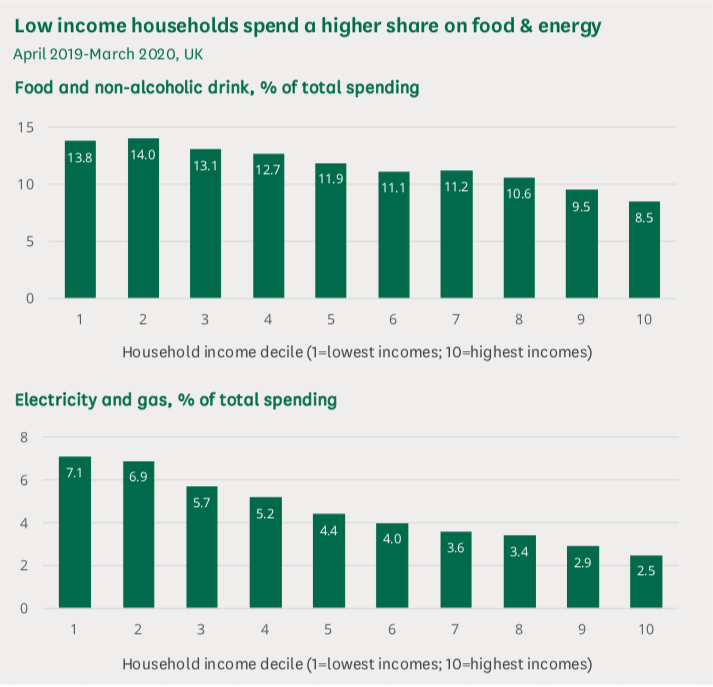

The inability of many people in work to afford items we would consider essential is precisely the problem; the price of food and energy are the top two reasons behind UK adults reporting an increase in their cost of living. Unsurprisingly, lower-income households are the most affected by rising prices as they spend a larger proportion of their income on energy and food. Worse still, lower-income households are facing inflation rates around 1.5 percentage points higher than higher-income households due to rising energy prices.

Source: House of Commons Library

Unfortunately, there are no immediate fixes. But there are a few reforms that the Government could enact to reduce in-work poverty. Firstly, it could help to reduce some of the higher costs facing workers through enacting supply-side reforms. This would include reforming our hideously outdated planning laws in order to drive down house prices, and relaxing child:staff ratios to reduce childcare costs.

Secondly, it could reduce the tax burden on workers. One simple way of doing this would be to index tax brackets, in particular the Personal Allowance, to inflation in order to eliminate fiscal drag.

Thirdly, it could seriously consider introducing a system of Negative Income Tax, (NIT), which would act as a minimum income guarantee, tapering away as peoples’ wages rose through work.

Fourthly, it could stimulate an increase in productivity, which is linked to workers’ wages, through replacing the super-deduction policy, thereby incentivising greater investment in capital. At present, the UK is forecast to be the slowest-growing economy in the G7 by 2023—if the Government is serious about wanting the UK to be a high-wage economy, this is something that needs addressing.

The outlook for those on lower wages over the next couple of months is bleak. The Conservative Party will not do itself, nor the public, any favours by complaining that Britons simply ‘aren’t working’ and reproaching a ‘culture of dependency’ which they have served to entrench through failing to enact necessary reforms for economic growth, rather than accurately diagnosing the problem.