NIT or UBI, that is the (economic) question

The Negative Income Tax (NIT) and the Universal Basic Income (UBI) schemes are often mistakenly interpreted as the two sides of the same coin. This is mainly because both policies aim at tackling poverty through redistributive taxation. However, both from an economic and ethical standpoint, these two policies present differences that should not be disregarded.

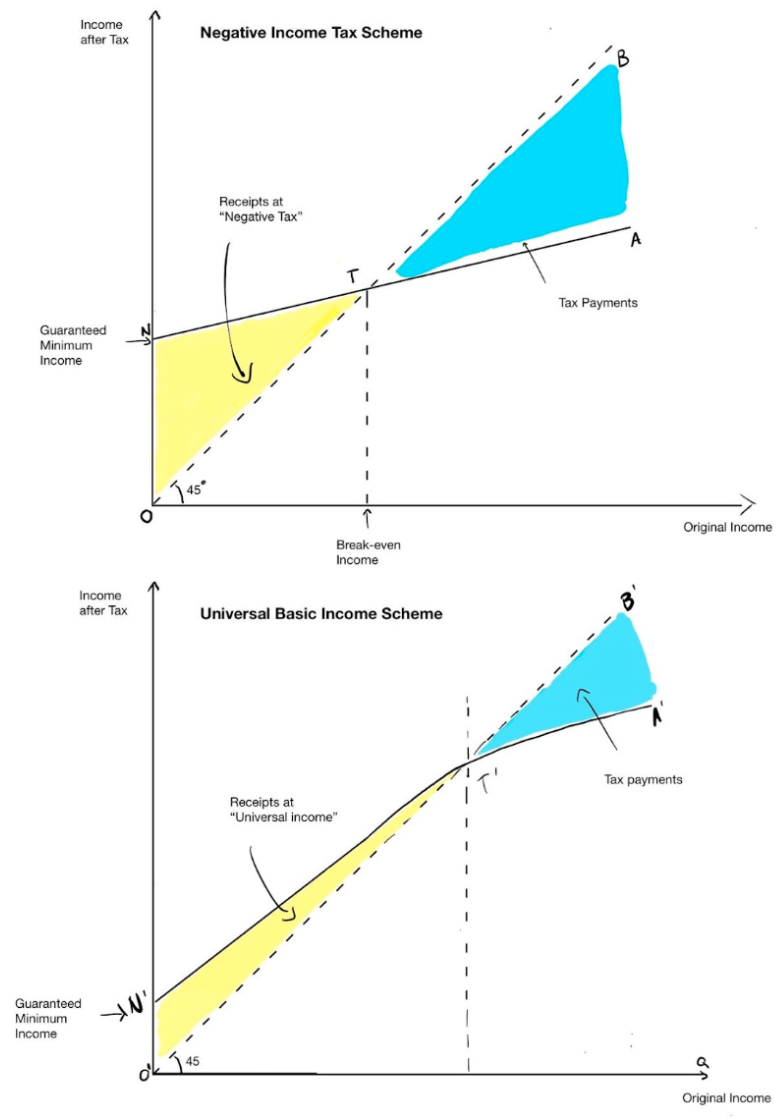

Economically, a NIT can be understood as a tax system associated with a tax deduction, as it proposes a scheme where at the “break-even” level of income, households pay no income tax. Above this level, households pay tax at a constantly increasing marginal rate on each additional pound while, below this level, they receive a payment of such rate at an inverse ratio. In the case of NIT, we can therefore observe a tax transfer (represented by the area NTO in Figure 1) that diminishes as income increases at a rate of -t and becomes zero when an individual’s income reaches the threshold T. Once income surpasses this threshold, taxpayers begin to pay a positive tax, quantified by the area TAB.

On the other hand, the UBI scheme entails the regular distribution of a uniform cash payment to individuals, irrespective of age, without any conditions attached. Realistically, a millionaire will receive the same payout as those currently on Universal Credit. Hence, in the case of UBI, the implementation of a universal and unconditional transfer ON’ to all individuals causes a permanent shift along the 45° line. Following the redistribution, individuals with a gross income below OT’ receive a positive benefit resulting from the disparity between the sum of UBI (represented by ON’) and the taxes paid, measured by the vertical gap between the translated 45° line and the income paid by the firm. Conversely, taxpayers with an income exceeding OT’ will incur a net tax payment.

Figure 1: Economic assessment of NIT and UBI

To ensure that the total benefits provided by a NIT and UBI program are equivalent, the area ONT in the NIT scheme must equal the area ONT’ in the UBI scheme, considering a normal distribution of individuals.

As clearly evident in Figure 1, a NIT scheme benefits individuals with low pre-tax income, but beyond the threshold T, it disadvantages individuals who would receive a higher disposable income under the UBI option. By ensuring equal net costs for both schemes, in a NIT scheme, a minority of poor individuals is therefore supported by middle and high-income taxpayers whereas, in a UBI one, wealthier individuals contribute to redistributing income to middle and low-income individuals. A NIT program has therefore a more pronounced impact on reducing labour supply among low-income earners compared to UBI. From a distributive perspective, NIT exhibits greater effectiveness in combating poverty, but the presence of high marginal tax rates on low incomes might discourage the same individuals to work. Conversely, in the case of UBI, the lower benefits for impoverished individuals, coupled with lower marginal tax rates, incentivize greater participation of low-income individuals in the labour market at the cost of a lower effectiveness in tackling poverty.

Let us all praise the planners

Apparently we should all be installing heat pumps real quick and right now. Germany’s Greens seem to have a problem with doing so:

Germany’s Greens are facing ridicule over reports that they have failed to install a heat pump in their party HQ, despite pushing for a nationwide switch to the technology.

A project to install the device at the eco-party’s headquarters in central Berlin has taken three and a half years because of a variety of problems that include difficulties finding qualified tradesmen and a two-year wait for a drilling permit, Der Spiegel magazine reported.

OK, so that’s just a ha ha, gurgle sort of observation. Even though it has obvious implications for the current insistence that everyone in this country must have one immediately. But those planners are not done yet:

Households have been saddled with three million faulty smart meters in a botched roll-out that is ballooning over budget, a report reveals today.

It had to be done quickly, you see? But that’s OK, it was really important and ministered by those planners so nothing could go wrong, could it? Rolls Royce minds and all that?

But of course these are mere trivia. Except, well, no. Those first generation biofuels not only starved the poor they had higher emissions than fossil fuels. The idea that Drax burning North American woodchips is CO2 neutral is laughable. Although for a real bellyacher try the Germans again, who actually have torn down a wind farm to get at the cheap brown coal, the lignite, underneath.

The connecting point here is that the planners aren’t very good at planning. Therefore we shall have to stop using planners.

This is entirely different from the logical points usually made about planning - that it’s impossible to have the information, all that Hayek and Nobel Lecture stuff. Instead it’s just the simple observation that our society has put the dullards into the planning offices. Best to keep them safe there and us out here safe from them by not using planning.

Britain's less productive because we're going green

British productivity numbers have not been doing well these recent years. As we all also know we’ve been building out those renewables over that same time period. These two things are connected. In fact, the one is causing the other.

Just to remind, productivity is the value of output divided by the number of labour hours. This means that if labour is used to produce something more valuable then productivity is going up. It also means that if more labour is used to produce something of the same value then productivity goes down. The other thing to know is that while productivity isn’t everything it is, in the long run, pretty much everything as a determinant of lifestyle and wealth. Rising productivity makes us richer.

The IMF has thoughts on this (page four, here). Coal and natural gas require 0.21 job years per GWh of electricity produced. Wind requires 0.32. Replace coal and gas with wind power and productivity declines and we get poorer.

No, this is not arguable. This is simple fact. It might be worth it to save Gaia, that’s at least logically possible. But it is indeed simply true that wind requires more labour therefore lowers labour productivity. Of course, by the same standard, solar requires 1.5 man years so solar is one seventh as productive as coal or gas.

So, what have we been doing recently? Closing down coal and gas in favour of wind and solar. We’ve been deliberately reducing labour productivity.

As we say, maybe this is worth doing for Gaia. But there are those out there who have the nerve to complain about the productivity numbers - exactly the same people who desire those renewables. That’s just damn cheeky. Worry about one or the other by all means, but don’t demand the one then complain about the results of your own insistences.

Do you want NITs?

Lorenzo is an intern at the Adam Smith Institute.

Some argue that the current UK welfare state discourages people to work, rather than specifically targeting low-income individuals.

An example of such policies are the Jobseeker’s Allowance (JSA) and the Income Support (IS) (Niemietz, 2010). As a matter of fact, these welfare-enhancing policies impose elevated implicit marginal tax rates on the most vulnerable segments of the labour market (Blundell et al., 1998; Meghir and Phillips, 2008), essentially functioning as an additional income tax for individuals receiving transfers who strive to go back to the labour market. Consequently, they give rise to detrimental effects on labour dynamics, as clearly highlighted in Table 1.

Adam et al. (2006) find indeed that, as the ratio of benefit income without work to disposable income in a low-paid occupation increases, the share of working adults strongly decreases. Despite recognising that there might not be a causal link between the two, the authors conclude that UK benefits might discourage job-seeking and return to work.

These policies extend economic support to a significant portion of the population including those who do not necessarily require it, rather than providing incentives for individuals with the lowest incomes to work and escape poverty.

As Table 2 shows, government transfers have evolved into a regular source of income across various income levels, as opposed to being limited to those with the lowest earnings (Office for National Statistics, 2020).

In 2019-2020, the 5th, 6th and 7th income decile groups, namely the middle and upper-middle class, received a higher percentage of benefits than the lowest decile group. This is mainly because the coverage of a spending programme, as opposed to its net distributional impact, is a much better predictor of its popularity (Niemietz, 2010).

The advantages of a Negative Income Tax

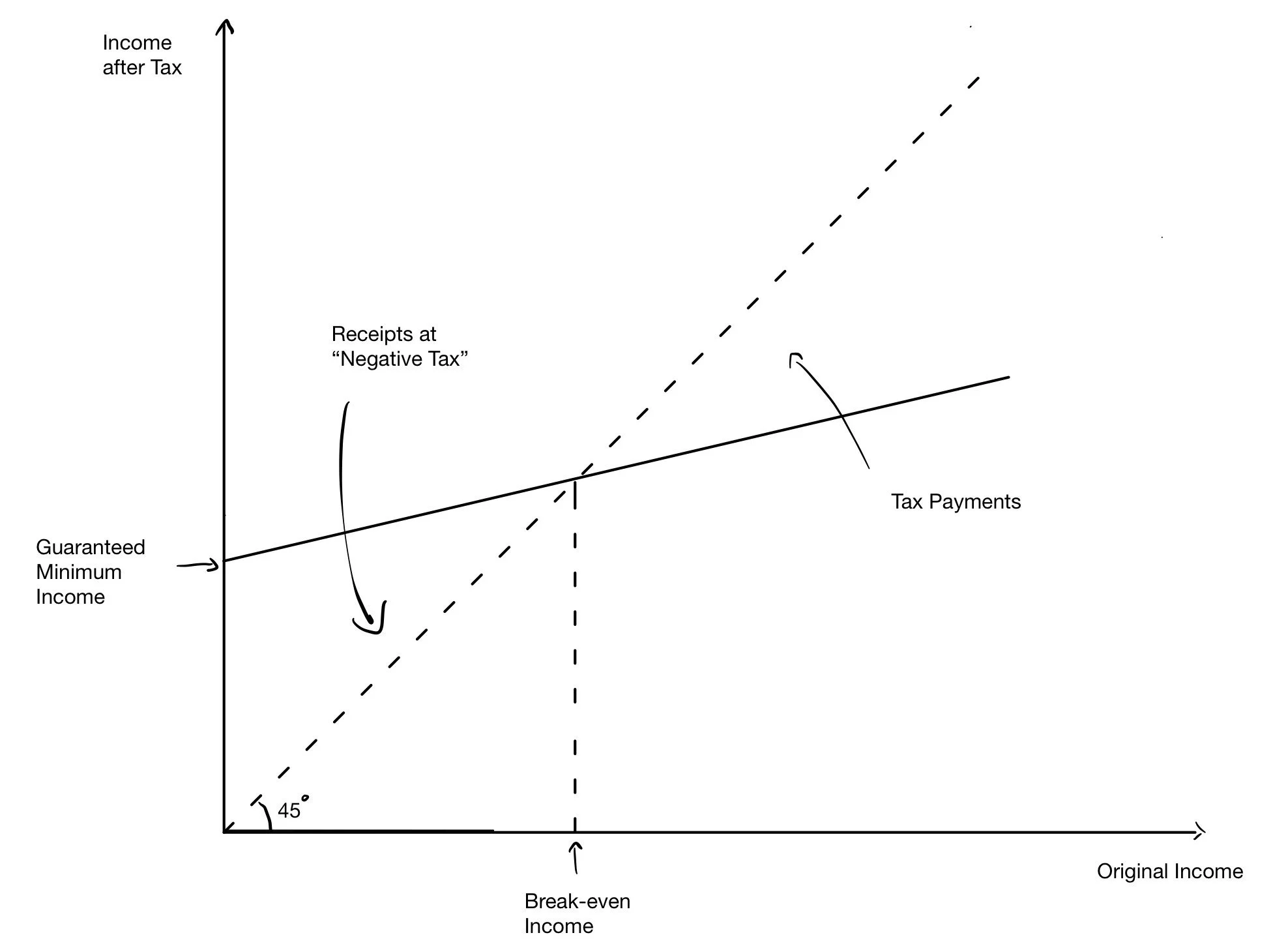

A negative income tax (NIT) supplements the incomes of the poor by achieving systematic structure of marginal rates, without poverty trap problems or cliff-edges. According to Friedman (1962)’s proposed scheme, at a “break-even” level of income, households pay no income tax (Figure 1).

Above this level, households pay tax at constant rate on each additional pound while, below this level, they receive a payment of such rate for each pound by which income falls short of the breakeven level tax.

This net benefit can therefore be considered a "negative" income tax as it makes the income tax symmetrical. Under such a proposal, some households would now pay no taxes, others would pay less taxes than before while other households with relatively high incomes would be unaffected (Tobin et al., 1967).

NIT’s main advantages are therefore claimed to be reducing poverty, supplementing the incomes of low-income earners, reducing expenditure on social security, welfare and administrative costs as well as contributing to the development of social capital (Humphreys, 2001).

Empirical Evidence

From 1968 to 1980, the U.S. Government conducted four experiments on the NIT, while the Canadian government conducted one, aiming to evaluate the policy's effectiveness and economic viability.

Some scholars argued in favour of the policy's success as the experiments did not find any evidence suggesting that a NIT would cause a portion of the population to withdraw from the labour force (Robins, 1985; Burtless, 1986; Keeley, 1981).

On the other hand, some scholars declared the failure of the policy based on two main arguments.

First, there was a statistically significant work disincentive effect for some subgroups such as primary earners in two-parent families, allowing scholars to conclude that a NIT discourages certain people to work.

Second, the work disincentive would increase the cost of the program of about 10 to 200% over what it would have been if work hours were unaffected by the NIT (Rees and Watts, 1975; Ashenfelter, 1978; Burtless, 1986; Betson et al., 1980; Betson and Greenberg, 1983).

Despite its theoretical economic advantages - reducing poverty by supplementing the incomes of low-income earners until they reach better paid work as well as lowering expenditure on benefits payments, welfare and administrative costs - further field research is required to assess NIT overall efficiency and economic feasibility.

Bibliography

Adam, S., Brewer, M. and Shephard, A. (2006) ‘Financial work incentives in Britain: Comparisons over time and between family types’, Working Paper 06/2006, Institute for Fiscal Studies.

Ashenfelter, O., 1978. The labor supply response of wage earners. In: Palmer, J.L., Pechman, J.A. (Eds.), Welfare in Rural Areas. Brookings Institution, Washington, DC.

Betson, D., Greenberg, D., (1983). Uses of microsimulation in applied poverty research. In: Goldstein, R., Sacks, S.M. (Eds.), Applied Policy Research. Rowman and Allanheld, Totowa, NJ.

Betson, D., Greenburg, D., Kasten, R., (1980). A microsimulation model for analyzing alternative welfare reform proposals: an application to the program for better jobs and income. In: Haveman, R., Hollenbeck, K. (Eds.), Microeonomic Simulation Models for Public Policy Analysis, vol. 1. Academic Press, New York.

Blundell, R.; Duncan A., Meghir, A., (1998) ‘Estimating labor supply responses using tax reforms’, Econometrica, 66, 4, 827-861.

Burtless, G., (1986). The work response to a guaranteed income. A survey of experimental evidence. In: Munnell, A.H. (Ed.), Lessons from the Income Maintenance Experiments. Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, Boston

Friedman, M. (1962). Capitalism and Freedom. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Humphreys, J. (2001). Reforming wages and welfare policy: six advantages of a negative income tax. Policy: A Journal of Public Policy and Ideas, 17(1), 19-22.

Keeley, M.C., (1981). Labor Supply and Public Policy: A Critical Review. Academic Press, New York.

Meghir, C. and Phillips, D. (2008), ‘Labour supply and taxes’, Working Paper 08/04, London: Institute for Fiscal Studies.

Niemietz, K. (2010). Transforming welfare: incentives, localisation and non-discrimination. Institute of Economic Affairs.

Office for National Statistics (2020) “Working and workless households in the UK: April to June 2020”

Rees, A.,Watts,H.W., (1975). An overview of the labor supply results. In: Pechman, J.A.,Timpane, P.M. (Eds.),Work Incentives and Income Guarantees: The New Jersey Negative Income Tax Experiment. Brookings institution, Washington, DC.

Robins, P.K., (1985). A comparison of the labor supply findings from the four negative income tax experiments. Journal of Human Resources 20 (4), 567–582.

Robins, P.K., Brandon, N., Yeager, K.E., (1980). Effects of SIME/DIME on changes in employment status. The Journal of Human Resources 15 (4), 545–573.

Widerquist, K. (2005). A failure to communicate: What (if anything) can we learn from the negative income tax experiments? The journal of socioeconomics, 34(1), 49-81.

It's never us that's the problem, is it, it's always them, the other

Apparently climate change is all the creation of a few fossil fuel company billionaires and entirely nowt to do with any of us:

It makes sense that anyone facing conditions as awful as those caused by the smoke this week would get angry. The trick is to get angry at the right people: fossil fuel billionaires who couldn’t care less about the horrors they’ve unleashed.

We’ll leave aside the obvious logical comparison here for simple good taste reasons, but there’s a definite side of human nature that wants to blame everything that goes wrong, whatever goes wrong, on that other. It’s them over there, not us. No, really - they’re to blame, just couldn't be cute and cuddly us now, could it?

Varied attempts have tried to blame things on the Trots, the bourgeois, wreckers, whites, colonialism, The English, Rosicrucians and the Illuminati. But climate change, whatever we might think of how bad it is or isn’t, isn’t something being done to us - certainly not us rich world folk. It’s something we’re doing.

Consumer demand fuels these companies’ decisions, to be sure.

Well, yes. Without the demand to be able to transport ourselves, heat our lives, cook our food - even have food grown that we can eat - there would be no climate change. There also wouldn’t be 8 billion of us either and most human beings do rather like being able to live (that’s a testable proposition, the number who don’t equals the suicide statistics).

The fossil fuel billionaires are only such because we like to transport ourselves, heat, have and cook food and so on. There is no “other” forcing this upon us. It’s also true that there’s no solution to climate change - if one is even needed - without us out here changing our behaviour. Expropriating, eliminating, even topping on Tower Hill, those fossil fuel billionaires won’t change that in the slightest.

The entire system is based on our desire for the ability to drive off for a hot steak in a warm room. There is no “other”, other than us, causing it all. Nope, not even the Rosicrucians. Nor the Illuminati.

Climate change is not in the billionaires or the fossil fuel companies dear Brutus, it is in ourselves.

America’s Exceptional Experiment in Self-Government

I was very pleased to receive a new ‘think piece’ by Tom C Veblen — yes, he is related to the great Theory of the Leisure Class author, and his daughter worked at ASI for a while too. His piece is called America’s Exceptional Experiment in Self-Government and it imagines a cultural and political revival of that great nation, now struggling through its self-induced cultural and political mess.

Among other things, Veblen cites a guide for surviving a seaplane crash on water. When that happens, they tend to come to rest upside down, so you need to have your wits about you. You must stay calm. Grab your life vest. Open the exit and work out your escape route before releasing your seat belt. If the obvious way out is blocked, work out another before you unbuckle yourself. Don’t let go until you are out. If you are underwater, follow the bubbles to the surface. Then inflate your life vest.

Veblen says it’s an analogy for ‘getting out alive’ from the wrecked political systems we have, and the more you think about it, the more apt the analogy is.

You need to stay calm. Too many politicians see problems emerging — inflation, for example, leading to widespread complaints and strikes over pay, rising borrowing costs, falling house prices and soaring prices for essentials like food and energy — then rush into some ‘quick fix’ solution that actually makes things worse. Like huge domestic heating subsidies to households, both rich and poor, which require vast new public borrowing to finance.

Or windfall taxes on oil producers alongside calls to cap energy prices, which have the effect of driving energy investment out of the country. Or capping the price of bread and milk and other basic groceries, which (as the author of Forty Centuries of Wage and Price Controls can tell you), won’t work and will just lead to shortages.

No quick fixes will get you out of this crash. You need to grab your life vest, the thing that’s going to keep you afloat. And that life vest is what Adam Smith (whose 300th birthday we celebrate this month) called the ‘simple system of natural liberty’. Make sure your money is sound, protect the basic institutions of open markets, competition, individual liberty and the rule of law. Leave people free to go their own way, and they will collaborate and boost value and progress before any government bureaucrat has even got the spreadsheet functioning.

Then you need to work out your escape route. That’s not always easy, as we discovered during the early 1980s, when Margaret Thatcher’s government tried to roll back a bloated state. Efficiency experts were brought in, and when they left again, things reverted back to their sad normal. We needed instead to work out a way to get the all-dominating nationalised industries (utilities, communications, transport, manufacturing and all the rest) out of state protection and into the chill wind of competition. The solution to each was different, and some worked better than others. It’s not easy to find your way out of a crashed state.

Follow the bubbles — look at what other people round the world are doing that actually works, and do that, rather than clinging to some ideological totem pole like the National Health Service. And, when you have done all that, distance yourself from the wreckage and inflate your life vest. Deploy the system of natural liberty, and you can float free.

Something we actually agree with

John Naughton tells us that:

We got to the point of thinking that if all that was needed to solve a pressing problem was more computing power, then we could consider it solved; not today, perhaps, but certainly tomorrow.

There are at least three things wrong with this. The first is that many of humankind’s most pressing problems cannot be solved by computing. This is news to Silicon Valley, but it happens to be true.

It’s also news to all those who would plan the economy. Allende was one of those who fell prey to this delusion - computers were going to run that Socialist Chilean economy. But it’s been a phantasm all the way back to those first stirrings of scientific socialism. If only we could calculate then we’d be able to plan!

No, actually, we can’t. We do not have, cannot have, the information required to feed into the starting point of however much computing power we have available.

While Hayek was right here, an excellent outlining of the problem in detail is this. The most important part of which - after the intractability of the actual computing problem - is what is it that we’re trying to plan?

We want to optimise some form of social utility function. OK, so what is that? The sum and aggregation of all of the individual utility functions, obviously. So, what are they? Well, we don’t know. Because utility functions are something we back calculate. We observe what people do given what’s available then write that down. But if we have to observe behaviour in order to work out what people want then we cannot plan what will be made available as we don’t know what will maximise utility in that new situation created by the plan. We can’t just ask people because that’s expressed preferences and we know that doesn’t define utility - revealed preferences do.

Naughton is quite right, not all problems are amenable to more computing power. The direction and planning of the economy among them.

Britain doesn't have enough second homes

From Theodore Zeldin’s “The French” (1983):

Almost one in every six families has access to a second residence

Translate that into British, we’ve some 25 million households, there should be 4.25 million second homes.

According to George Monbiot we have rather fewer:

Before the pandemic, government figures show, 772,000 households in England had second homes. Of these, 495,000 were in the UK. The actual number of second homes is higher, as some households have more than one; my rough estimate is a little over 550,000.

We are, thus, short some 3.75 million second homes. If we wish to be like the French that is.

This is more than just snark - tho’ snark is always fun. The important thing to understand about housing across cultures is that each is a technology. A machine for living in. And those cultures, technologies, which have people living in dense urban cores, in apartments, also have the wide ring of summer places surrounding them. This is true - from personal experience of people here - for Germany, of the Czech lands, or Russia (to the point that one of us has endured a lecture from a Soviet car factory manager on the importance of providing dachas for the workers. And it was important, growing your own was the only way you’d get vitamins, let alone vegetables.) No, an allotment is not the same thing - it is illegal to even think about staying overnight on an allotment. All these country places will have at least a shack with bunks.

The Southern European towns tend not to have gardens attached even to the houses, let alone the flats. But they have different inheritance practices (real property must, by law, be divided equally among all kids) and are also several generations closer to the land. At least a part share in Granny’s hovel out in the country is near universally available.

Those stack-a-prole worker flats that our UK urban planners think we should all live in are only part of that whole housing technology. By observation that works only with that addition of the second place in pulchra agris. The British solution to the same idea, that housing technology as a whole, has been the des res with front and back garden and on that quarter acre plot of land. Exactly the thing that is now illegal to build given required densities of up to 30 dwellings per hectare.

They’re technologies. Suburbs of housing with gardens, or flats with second houses. They’re integrated technologies, things where you need both parts to make them work. Our British planners have decided to go off half-cocked with only half of either technology. They’ll allow the house but not the garden, the flat but not the shack in the country.

We might have mentioned before that we really don’t like planners or planning. This is one of the reasons why - the planners we actually get are ignorant.

Banning ultraprocessed foods

We are aware that Sir Simon did not write the headline but:

Banning ultra-processed food is not a nanny-state issue. It’s common sense

So, on the basis of a laughable book from Dimbleby fils (the man, recall, who made his money selling fish finger sandwiches) we should ban:

Fizzy drinks (sugary or sweetened); crisps and packaged snacks; chocolate, confectionery; ice-cream; mass-produced packaged breads and buns; margarines and other spreads; biscuits, pastries, cakes; breakfast ‘cereals’, ‘cereal’ and ‘energy’ bars; milk drinks, ‘fruit’ yoghurts and drinks; ‘instant’ sauces. Many preprepared ready-to-heat products including pies and pasta and pizza dishes; poultry and fish ‘nuggets’ and ‘sticks’, sausages, burgers, hot dogs, and other reconstituted meat products; and powdered and packaged ‘instant’ soups, noodles and desserts. Infant formulas, follow-on milks, other baby products.

That is actually the recommendation. Or as it can be put, “Enjoy your turnips, serfs”.

We’d actually enjoy watching someone try to do this. But then we do have that anarchist love of watching riots and chaos in the streets. For there’s just no way that this could be done in a free society or without them. Therefore it will not be done. But as we say, it would be fun watching someone try.

Our own opinion is that this is just another version of the desire for sumptuary laws, as with the hopes for bans on fast fashion. If even the poor can have a change of clothes, interesting food, then what’s the point of being privileged? Therefore those things that enable the poor to be as their betters must be banned.

It’s a very common and very unattractive part of human nature.

The other way to look at this is as a proof of Hayek’s contention in The Road to Serfdom. If government becomes the provider of health care - the NHS - then the population will be managed at the pleasure of the health care system.

Bank balance

The UK financial sector, one of our most important industries, has had its share of problems and faces more than its share of challenges.

The uncertainty about Brexit and access to European markets, specifically the lack of much positive government action to capture the advantages of Brexit, does not help. Also, business is still flat since the Covid lockdowns; additionally, commercial property has been hit and more people are defaulting on loans.

Higher interest rates have hit the mortgage market too. Then there is Fintech (financial technology) which is challenging some of the traditional players, like the high street banks. Though customers are increasingly demanding digital banking, their systems are largely stuck in a previous era — thanks to the laziness that comes from having a cosy regulated market rather than one more open to new competition.

Plus all the problems in the pensions sector — investment conditions and the multiplicity of pension plans, and the general lack of transparency in pensions (need I say over-regulation by a jealous Treasury?). And there is growing competition from other financial sectors such as New York and Singapore (which again, is a direct result of the UK government’s over-taxing and over-regulating).

So what is to be done? Lower taxes on UK businesses would help. Instead of companies (and their financial needs) going abroad, or not coming to the UK in the first place, we need to attract businesses in and induce them to say. And encourage people to start new businesses too. High tax, by increasing the risk in already risky ventures, kills business creation stone dead.

We need more competition, too. Right now, getting a banking licence out of the regulators is like getting a smile out of a stone. The barriers to entry should be a lot lower. Right now, we are regulating banks as if they are all enormous, and that their failure would be a national disaster — as the failure of big banks was in the 2008-09 financial crisis. (And what did Gordon Brown do about it? He forced banks to merge, creating institutions that were arguably safer but which were even more ‘too big to fail’. ) And yes, if we have institutions that we really cannot afford to lose, they should indeed be carefully regulated.

But new, small banks are different. If a small bank fails, it’s a very limited disaster, not a nationwide one. We can get over it. Even if deposits are guaranteed by the taxpayer, the amounts at risk are manageable, unlike the 2008-09 bank bailouts, which saw government debt soaring and gave us much of the debt overhang we have today. It is quite possible too that customers of new banks are more aware of the risks than customers of large and established banks; so perhaps the need for taxpayer bailouts is less.

So the answer there is to have banking regulation that reflects the existential risk (or lack of it) of the institution. Large ‘too big to fail’ banks should have tough regulation, small ‘if it fails we can deal with it’ banks should be more lightly regulated. That would encourage more competition in financial services, and therefore greater focus on customers and keeping customers safe, instead of regulator-focused box-ticking complacency.