We've been waiting for this change of strategy from Oxfam

Oxfam tells us that they’re going to stop fighting poverty and concentrate on the battle against inequality instead:

Why Fighting Inequality Is at the Heart of Oxfam’s New Global 10-Year Strategy

They really are quite clear about it:

We used to talk only about poverty. No more.

Those who merely wish to alleviate poverty out of that desire to aid a fellow human will have to look elsewhere then.

Oxfam’s new mission is that we will fight inequality to end poverty and injustice.

We’ve seen this before. Here at home in the UK. There was a time when all points left - and classical liberals were definitely part of that back then even as we insist we are now - wanted to alleviate poverty. So, that’s what was alleviated. As Barbara Castle pointed out in 1959, destitution was a thing of the past by then. We did in fact go and conquer that poverty. By economic growth, the thing best promoted by capitalist free marketry.

Much of the rest of the world still suffered it of course. Then that neoliberal globalisation took hold and we had the greatest reduction in absolute poverty in the history of our species. Current best guesses are that it’ll be entirely gone, that $1.90 a day destitution, within the decade. That happening as it did here domestically, economic growth through capitalist free marketry.

That domestic disappearance was a problem for those who wanted something to moan about. Therefore the definition of poverty was changed to a relative measure - to inequality. Now we’re seeing the same internationally. What point an international organisation, like Oxfam, to beat poverty if poverty is beaten? Quick, quick, change the goal so that there’s a reason for the continued existence of the corpus bureaucraticae.

There has to be, after all, some reason why those against capitalist free marketry can have an excuse to agitate against capitalist free marketry. If that neoliberal globalisation has beaten poverty then find something else. Without, of course, celebrating or even acknowledging the victory caused by that thing so despised.

We would say that this is a bureaucracy thrashing around to find a reason for its continued existence. But then we would say that, wouldn’t we?

Look on the bright side though. If the rich world upper middle classes who actually get those indoors, no heavy lifting, jobs at Oxfam insist that a new justification for their gravy train must be found then we do indeed have good evidence that poverty - proper, real poverty - is well on the way to being beaten, don’t we?

Just to hammer the point home:

Practically, we will focus on four interconnected areas: advocating for fairer, just economies; striving for gender justice and for the rights of women in all their diversities; pushing for climate justice; and ensuring that the powerful are held to account.

We would interpret that as they’re going to stop actually doing anything other than issuing press releases. Pity, they used to actually do some rather good actual work.

Draft text of The United Kingdom Free Speech Act

I was caught off guard by the warm reception of my latest ASI paper: Sense and Sensitivity: Restoring free speech in the United Kingdom.

It was covered by Guido and the Telegraph, as well as shared thousands of times across multiple platforms. A number of political types have also reached out to express interest in discussing these ideas further. I couldn’t be happier to see people so engaged.

But it occurs to me, 72 hours later, that I forgot something.

The paper called out government shenanigans with freedom of expression and proposed for five concrete policy changes:

Removing the words “abusive” and “insulting” from the Public Order Act 1986.

Limiting the scope of Section 127 of the Communications Act 2003 to threatening language only.

Replacing the harassment component of Section 127 of the Communications Act 2003 and the Malicious Communications Act with a harassment/cyberstalking statute similar to 18 U.S. Code § 2261A, with its higher thresholds for criminal conduct as a replacement.

Repealing the Malicious Communications Act 1988.

Enacting the UK Free Speech Act.

Item 5 is where I came up short. I didn’t offer any proposals for what the UK Free Speech Act might actually say, although I did state what I thought it should seek to accomplish.

I am cognizant that a discussion draft is always a more helpful starting point than a proposal. Therefore, for discussion purposes, I propose the following:

UK FREE SPEECH ACT [2021]

An Act to secure the free and open flow of information and ideas for the people of the United Kingdom.

Be it enacted by the Queen’s most Excellent Majesty, by and with the advice and consent of the Lords Spiritual and Temporal, and Commons, in this present Parliament assembled, and by the authority of the same, as follows:—

SECTION 1. FREEDOM OF SPEECH

(1) The right of any person, and of the people, to freedom of speech shall not be violated by the state.

(2) Freedom of speech encompasses but is not limited to the right to engage in spoken or written expression of any idea pertaining to any matter of public interest, morality, philosophy, or politics, which is not a threat or direct incitement.

(3) “Direct incitement” means speech or writing which is directed towards inciting or producing imminent lawless action and is likely to incite or produce such action.

(4) Schedule 1, Part I, Article 10 of the Human Rights Act 1998 is hereby repealed.

And that’s it.

The text here is not designed to be all-encompassing, but rather to permit the judiciary to do its job in ascertaining the proper application of the statute in situations which Parliament may not have intended or been able to conceive of at such time that a Bill like this was passed.

Section 1(1) states that “freedom of speech” is not to be violated. The right is expressed to be both individual and collective. The exact boundaries of this right are left to be determined by the judiciary. It is expressed to be enforceable against the state. This should be read as applying to any public body and any private body performing a public function, and not to any other private body or private person. The exact details, including standards of judicial scrutiny to state actions which infringe these rules should be left to the courts, which are toying with playing a greater constitutional role (see e.g. the 2019 prorogation of Parliament) and will eventually do so one way or another.

Section 1(2) states an irreducible core of the new freedom of speech which cannot be restricted in nearly any circumstance, and which protects speech on matters of public concern which are neither a threat nor direct incitement. It limits itself to speech or writing and deliberately does not address weird performance art or the assembly of objects e.g. Tracey Emin’s Unmade Bed. This section does so because speech and writing which is neither threatening nor incitement is the least likely type of expression to cause any person to suffer direct physical harm or to create standard-of-review constitutional issues that British courts are, doctrinally speaking, poorly equipped to address. These forms of expression are also easy to avoid by those who do not wish to read or listen to them.

The wording should grant latitude for the courts to both expand the right where appropriate (as in the case of performance art) and restrict it in the case of private concerns (e.g. harassment or defamation) while also drawing a bright red line around speech which is most essential and most threatened by the Law Commission and the Scottish Parliament. But above all this sub-section would ensure that the core right – to speak and write – cannot be touched.

Section 1(3) incorporates the “imminent lawless action” test from Brandenburg v. Ohio, 395 U.S. 444 (1969), which operates to limit the scope of speech protection to only that speech which is likely not to incite others to commit a crime while also permitting advocacy which is unlikely to cause incitement. This is designed to bring the English system “up to speed” with the only system of speech regulation in the world that has so far held up in the face of censorial onslaughts for several hundred years. In other words, it allows the courts to stop truly dangerous people but prevents them from doing much about the merely annoying. The inclusion of this definition is necessary to abolish any common law residuum from the decades-long political misuse of the Public Order Act 1986 and similar rules.

Section 1(4) repeals Article 10 of the Human Rights Act and the European Convention. The right contained in this UK Free Speech Act is more robust than the Article 10 right and supersedes it, so the Act might as well repeal it. The rest of the Human Rights Act, which can just as easily be used to curtail rights as expand them (see the lengthy list of derogations permitted in the name of Article 10(2), for example) should eventually be scrapped and replaced with robust, enforceable civil liberties protections in domestic law similar to this one.

And that’s my proposal, offered for discussion and your reading enjoyment. Happy to hear anyone’s thoughts on its content. I’m easy to find.

One of those little problems with Modern Monetary Theory

Modern Monetary Theory - the magic money tree - is one of those ideas that contains within it the proof of its own problems:

Moreover, as these governments can repay their debts in their own currency, they always have the option to print money. This is a privilege not available to any household with their mortgage. This is a welcome departure from the austerity narrative preached by governments around the world in the aftermath of the 2008 crisis.

OK, that is MMT. Then we are told:

Most importantly, many poorer countries already face dangerous amounts of indebtedness, with 64 countries currently paying more on debt servicing than on healthcare. This is not the fault of the countries themselves, but the legacy of decades of neoliberal policies and the longer history of colonial inequality. As this debt is increasingly owed in foreign currencies, these countries do not have the privilege of printing money to repay their creditors.

Hmm, so, why are those countries not able to borrow in their own currencies? Why is it that people will only lend to them in monies that the borrowers don’t control the volume, issuance and thus value of?

The obvious reason being that lenders don’t trust them and their power over that issuance of money. To the point that they won’t lend to people who obviously do just print more money to pay off their debts.

That is, MMT only applies to people who, historically, haven’t used MMT. Which is something of a problem for the idea moving forward as when those who haven’t start to then the same will happen again.

The conservative revolution is in fact happening

The conservative that is, not Conservative, revolution:

About eight months ago, a fascinating social change began to ripple through hundreds of British neighbourhoods. Given the deluge of news that has happened since, it is easy to forget how remarkable it all seemed: droves of volunteers who were gripped by community spirit coming together to help deliver food and medicines to their vulnerable neighbours, check on the welfare of people experiencing poverty and loneliness, and much more besides. From a diverse range of places all over the country, the same essential message came through: the state was either absent or unreliable, so people were having to do things for themselves.

It’s possible to argue with that “have to” instead of desire to but still, the finding now is that it is preferred:

There and elsewhere, the key story of the Covid crisis has been that of town and parish councils enabling people to participate in community self-help.

Community self help might be this year’s buzzword for the process. But this is just - or perhaps is gloriously - Edmund Burke’s little platoons deploying for action. That appropriate technology - a method of organisation is a technology - for so many of life’s activities and problems. The voluntary association of those concerned to deal with what is in front of them. What’s not to like?

From the other side of politics, it is worth reading a recent report by the Tory MP Danny Kruger, commissioned by the government to look at “sustaining the community spirit we saw during lockdown, into the recovery phase and beyond”. Kruger proposes a new Community Power Act, using deliberative democracy, participatory budgeting and citizen assemblies “to create the plural public square we need”.

Well, obviously, there’s always someone out there willing to spoil a good thing. We’ve just found out that certain parts of life are better run without politics so politics must be reintroduced to them?

This is also of course the classical liberal as well as conservative position. That voluntary association provides the best method of dealing with many, but not all of, life’s processes. Sometimes it will be those little platoons. Sometimes it will be larger such voluntary cooperation - a supermarket chain is exactly that, a group of people that cooperates in order to produce retail services for the rest of us. Sometimes, if rarely, such spontaneous order doesn’t in fact work and then government is necessary.

But isn’t that an interesting finding from the recent pandemic? That the “rarely” is a lot more rare than our system previously assumed? At which point roll on the neoliberal, even if conservative and Burkean, revolution.

Legislators should legislate; governments should govern

As Britain’s best-known classicist, Boris Johnson, should know, the verb govern comes from the Latin gubernatori—what the helmsman does in taking the ship towards its intended destination. In this case, steering the ship of state. The state, of course, has three branches: parliament (the legislators), the judiciary and the government (the executive). The helmsman does not make the rules; the captain (i.e. Parliament) does. He sets and maintains direction, rather than running around the ship trying to fix whatever he thinks needs fixing.

The trouble with power is that it is addictive: instead of sticking to governing, the party in power fiddles with legislation (as has been especially apparent during the Covid pandemic) and tries to manage the many activities it should leave to others. Government would perform better if it focused on governing. As Lord Udny-Lister, now the PM’s Chief of Staff, once put it “If I'm to do the job properly, I've got to understand it, how it [in this case government] works, what makes it tick.”[1]

Lord Sumption has reminded us that government has no power beyond that prescribed in law. In practice, however, the distinction between the powers of government and parliament has become murky. Primary legislation is solely a matter for parliament but government has acquired excessive control over the Commons’ time availability and agenda.

Secondary legislation—statutory instruments (“SIs”)—are created by ministers, not MPs. A Commons Library briefing summarised their scale: “An average of 2,100 UK SIs were issued annually from the 1950s to around 1990. This then rose to an annual average of 3,200 in the 1990s, 4,200 in the 2000s, and fell to around 3,000 a year on average during the 2010s (to June 2019).” According to the Hansard Society, only 0.01% (11) were rejected between 1950 and 2017. The number of SIs has declined sharply since 2015: only 757 were laid before parliament in 2015/6, the lowest number in 20 years, yet they still comprised 7,783 pages of legislation. A few MPs spent a total of less than eight hours debating them, an average of four seconds per page, and then waved them all through.

If our legislators are so ignorant of their own laws, how can the rest of us be expected to know them? A law is useful only if those who are supposed to obey it are aware of it. The world’s oldest surviving parliament is not Westminster but Iceland’s Althing, founded in 930. As there were no written records, each session of the Althing began with the speaker reciting, from memory, all Iceland’s statutes. Any laws he forgot were no longer laws. This seems an excellent precedent.

Although excessive regulation is usually blamed on the EU, the House of Commons Library estimated that an average of only 13.2% of SIs, passed between 1993 and 2014, were EU-related. Nor are all SIs trivial: secondary legislation can be used to amend primary legislation. Around 20% of SIs are significant enough to require impact assessments on how they are expected to impact the private or voluntary sectors and the economy in general—providing a more realistic picture of the legislation decided by government.

From a high of 664 in 2011, the number of impact assessments steadily dropped to 170 by 2017. Alok Sharma’s Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy department deserves credit for that. Impact Assessments began about 20 years ago following the publicity given, notably by the British Chambers of Commerce, to over-regulation which was thought, in 1997, to be costing about £100bn pa or 10% of GDP. Regulation was critically reviewed by the Commons Regulatory Reform Committee in 2008 with 29 recommendations, including closer scrutiny by parliament.

The logic of legislators legislating and government governing leads to the conclusion that SIs should be replaced by four categories:

“Regulations,” accompanied by impact assessments, should be scrutinised, amended and decided by committees in both Houses when the private or voluntary sector is affected. The 29 recommendations of the 2008 Commons Regulatory Reform Committee should be reconsidered. Example: The Ionising Radiation Regulations SI 201/1075.[12]

“Legal amendments” of no impact on, or interest to, the general public or, probably, government, should be scrutinised, amended and decided by a specialist committee of the House of Lords only. Examples: Crown Court Amendment Rules SI 2017/1287, The Communications Act 2003 and the Digital Economy Act 2017 (Consequential Amendments to Primary Legislation) Regulations 2017 SI 2017/1285

“Local bye laws”, such as temporary road closures, flights over Edinburgh during Hogmanay (SI 2017/1299) and transferring small funds between Church of England schools (SI 2017/1294), should be devolved to local authorities.

The remaining SIs which should not be legislated at all, e.g. exhorting one government department to work with another, are matters for government, not parliament.

The role of legislators should also concern our Attorney General, Suella Braverman, but what about the rest of government? Clearly it should decide policies and use current law, guidance and the taxpayers’ money to bring them about. Using funding to influence behaviour makes sense but it needs to sharpen up its approach to guidance. The Department for Health and Social Care sprays out about 2,000 bulletins a year, a mix of guidance and “open government” with no targeting to the right people: one can either opt in and receive them all or opt out and receive none.

Neither is thought given to whether guidance is expressed in ways that would achieve compliance. Quite a few give the impression that they are legal instructions when they are not (or should not be). The guidance to care homes to keep people from seeing dying relatives is an example: “This supplements the legal position set out in the Health Protection (Coronavirus, Restrictions) (England) (No. 4) Regulations 2020.” Care homes took it as instruction to keep visitors out but actually it was simply advice that care homes and families “should work together” to decide the right balance.

For clarity and effectiveness, government guidance should:

Indicate that it is advice, not instruction, where that is the case. If it is instruction, the relevant legal authority should be cited.

Be targeted at relevant members of the public. People with no weight problems do not need guidance on their calorie consumption. Press releases should just go to the media.

Understand, from the recipient’s point of view, how the guidance will be received and therefore its likelihood of changing behaviour.

Not be issued at all if it will not help achieve the desired policy outcomes. Bulletins, such as officials’ travel expenses, which we only need to know if they are improper, should be placed on departmental websites with open access but not circulated.

In short, as Michael Gove has said, “we surely know the machinery of government is no longer equal to the challenges of today.” The performance of both Parliament and government will be improved if the former does all the legislating and the latter sticks to setting policies and using current law, guidance and its income to achieve them.

Allow us just to translate this particular report for you

There is, often enough, a certain difference between what is said and what is meant. That leads to there being a value in a translation, from the words used to the underlying meaning:

Middle-class problem drinkers who have turned to alcohol in lockdown are missing out on help because health services “are not designed for them,” says the president of the Royal College of Psychiatrists.

Leader of trade union for professionals wants to explain what we, the nation, can do for the members of his profession.

Dame Carol Black’s report is a rare opportunity to overhaul addiction services. It must commit to properly funding services by reversing the cuts and investing £374million into adult services over the coming years.

Give us lots of money.

Addiction services were taken out of the NHS and given to local authorities where contracts are re-tendered every three years. This creates a race to the bottom with contracts going to the cheapest bidder at the expense of specialist staff and training places.

Stop that silly nonsense of asking “How much?” and just hand it over. Don’t you know it’s uncouth to ask professionals to account for what is spent and how?

For many years, addiction services have borne the brunt of swinging cuts with funding slashed by over 25 per cent since the Health and Social Care Act was implemented in 2013.

You’ve all been entirely beastly for years now, not giving us enough of your cash.

The justification is that some of you have been having a second gin and tonic during lockdown. No, really:

But the reality is that alcohol dependence is rife in our warm and comfortable houses. It’s seen at the dinner table when that second bottle of wine is uncorked or when another large gin and tonic is poured, all done under the guise of socially acceptable drinking.

We will decide what is socially acceptable, thank you very much, because we’re the professionals here. And don’t be absurd and claim that mere members of society get to do that - what do you think this is, a liberal polity?

Now that we have that accurate translation we must all consider our reaction to the plan, the demand. We suspect that the correct one involves an Anglo Saxon Wave or two, somewhere in it…..

If only Owen Jones understood the merest smidgeon of economics

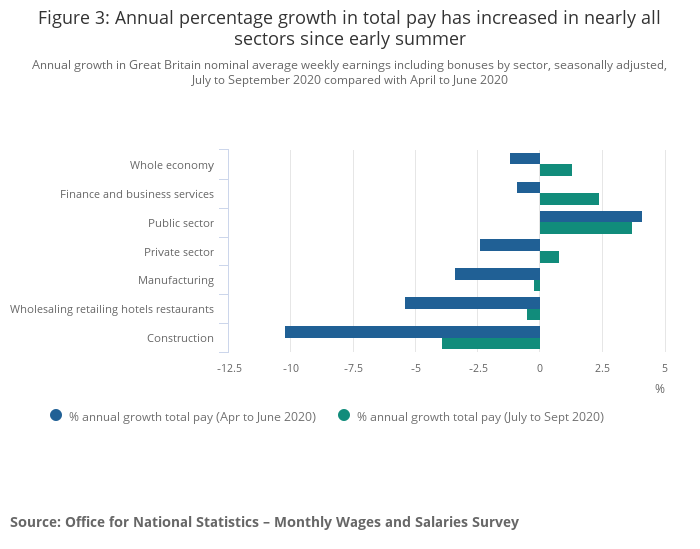

Yes, of course Owen Jones is going to complain about a public sector pay freeze. It would, however, be useful if he had even the merest, slightest, knowledge of economics to back up his indignation.

Reports suggest the chancellor, Rishi Sunak, will resuscitate divide-and-rule arguments, pointing out that private-sector workers have been worse hit than their public-service counterparts. Instead of aiming anger at the government for causing another lockdown and disruption to those working in retail or hospitality, we’re being asked to direct our venom at our neighbours who’ve been required to go into work every day to keep our schools, councils and social services running. If Britain had a rational political culture, the debate would centre on driving up the wages of private and public-sector workers alike, ensuring everyone has a decent day’s pay for a decent day’s work. Instead we are left with a race to the bottom.

Well, we could start with the actual numbers, which is that public sector wages have been rising recently, as private sector fall. Mutter something about fair shares of the burden and all that.

But Young Owen’s making a larger mistake here. GDP is about 10% below where it was. Therefore all incomes, in aggregate, need to fall by 10%.

Now it’s entirely true that GDP isn’t everything that’s good in this life and it’s not the only societal target we should have. However, GDP is indeed all value added in the society as measured at market prices. By construction it is also all consumption at those same market prices and also it’s equal to all incomes in the country.

This is simply the definition. OK, we might quibble a bit about GNI instead of GDP, but for the UK that is a quibble. That number which is now 10% lower is all incomes in the country in aggregate. That is, all incomes in the country must, in aggregate, be 10% lower.

How should we divide this pain? We could have 10% unemployment and so 10% of the people have no income. Although given the existence of the welfare state, which provides an income to those without a job, we’d need unemployment to be much higher than that. Perhaps we could wipe out all those corporate profits? Except, once we account for the labour share of the economy, subsidies and taxes on production and consumption, self-employed income, we find that capital share is about 20%, half of which is depreciation. So, we’d need to wipe out all profits from all investment. At which point we’d have no investment moving forward, something that would significantly lower the incomes of those who come after us, or ourselves in the future.

The logical and civil - even just and fair - manner of dealing with this is that all incomes fall a bit. Rather than some incomes disappear entirely.

Sure, we can shout that the economy, and thus all incomes aggregated, shouldn’t have fallen. Even, that we’ve a plan we’ve not told anyone as yet which would have prevented it. But we are where we are. GDP is 10% smaller, all incomes aggregated are 10% smaller. Now, who gets the pain?

It’s not, to put it mildly, obvious that those who work for the state shouldn’t have to carry any of that burden, is it? Especially since public sector compensations - so including terms and conditions, job security, pensions and the rest as well as wages - are significantly higher than private sector already. Isn’t it progressive to insist that the richer among us should carry rather more than in proportion of society’s burdens?

We've been telling the Fawcett Society for over a decade now

The Fawcett Society is, again, using the wrong numbers to describe the gender pay gap. Something we’ve been pointing out to them for over a decade now. Our doing so is even in the references to their Wikipedia page so you’d think they would grasp it by now. Apparently not though:

According to the Office for National Statistics, the mean gender pay gap for all employees is 14.6% this year, down from 16.3% last year. Fawcett calculates Equal Pay Day by using the full-time mean average gender pay gap – which this year is 11.5%, down from 13.1% in 2019.

That’s the wrong number to be using. As we, and the ONS, and the Statistics Authority, possibly Uncle Tom Cobbleigh ‘n’all, have been pointing out for more than that decade it must be the median used, not the mean. For wage distributions are hugely biased by there being a bottom limit of zero (while it’s possible to have a negative income we don’t measure them as such) and no obvious upper limit as footballers’ salaries show.

The thing is that the people making this mistake are aware of it. They must be for our same criticism has led them to abandon their earlier, even more misleading, comparison of part time to full time wages. They are, that is, actually numerate. This makes their behaviour worse of course. They know what they’re doing.

Until and unless they start using the correct numbers - and as we insist, they do know what they are - we can and should all ignore them. There are enough problems out there to be dealing with without taking note of those being, in our opinion, deliberately misleading about them.

The government declares that gas boilers are better than heat pumps

The government has just announced that gas boilers, that old technology, are better than heat pumps, that new, green and wondrous technology. That’s what is actually meant by the newly announced ban:

Gas boilers will be banned in all newly built homes within three years under the government’s plan to tackle climate change.

If the heat pump option was in fact better for consumers then there would be no need for the ban. Everyone would naturally gravitate to the better solution because that’s how us humans work. It’s also how technological advance works. We observe, ooooh, that looks good, we adopt and that’s how change happens.

The very insistence that the older technology many not be used is an admission, a declaration even, that the newer is not better.

Blinding us with Nonscience

The government decides, from time to time, that it needs to justify its intended course of action with science. But is that science or “nonscience”, selective statistics dressed up to look like science? Yes, we should reduce air pollution from vehicles and discourage excessive alcohol consumption; policies of this nature do not need spurious justification by bogus science. The SAGE committee has provided statistical extrapolations of their guesses of people’s reactions in hitherto unknown circumstances. This is known as “behavioural science” even though, because the conventions of science (theory – test – revise theory etc.) are not followed, it is not science at all.

This week saw the announcement that the sale of petrol and diesel motor vehicles will be banned from 2030. Fair enough. However it is based on nonscience published by Public Health England (PHE) in 2018. The authors are anonymous but the source is “the UK Health Forum (UKHF), in collaboration with Imperial College (the School of Public Health and the Business School), [which has] built on the UKHF’s existing flexible microsimulation model.” Perhaps unfairly, UKHF has been described as “a slush fund for 'public health' activists to lobby for the usual assortment of paternalistic anti-market interventions in lifestyle choices.” PHE seems to have come to the same conclusion because it withdrew funding from UKHF in the year following their document. UKHF then closed down.

PHE and the Department for Health have long commissioned work from the Centre for Social Marketing at the University of Stirling which, coincidentally, endorsed whatever PHE wanted to do. The Centre is headed by Professor Gerard Hastings who “also conducts critical marketing research into the impact of potentially damaging marketing, such as alcohol, tobacco and fast food promotion.” He authored “Europe’s only social marketing textbook: Social Marketing: Why Should the Devil have all the Best Tunes?”

The extent to which he who paid the piper called the tune should always be taken into account in assessing the credibility of academic research. Volkwagen notoriously fiddled the research they gave regulators. Imperial College has a strong relationship with the Department of Health and Social Care and there is nothing wrong with that. The funding for its School of Public Health research is not apparent from its annual report but, overall, government and health authorities are its third largest source.

In terms of provenance, the Imperial Environmental Research Group (ERG) under Professor Kelly is indeed impressive. The 2018 study would have been more convincing, however, if it had simply come from named ERG authors in the conventional way, and, better still, been published after peer review in a leading academic journal. As it is, we only have a mongrel.

Three areas are taken: Lambeth (high pollution), South Lakeland (low pollution) and England as a whole. South Lakeland is the area around Kendal, South Cumbria, with life expectancies about the national average. Life expectancy in Lambeth is much the same: 78.4 for men and 83.5 for women. It has been rising steadily, possibly due to air pollution.

The baselines in the PHE research were the years 2010 and 2015. Curiously, background pollution in South Lakeland seems to have declined over the five years but that was not commented upon. Fine particulates are treated as being 100% in the low category for South Lakeland with zero in the high category. Vice versa for Lambeth and one third in each of the three (high, medium and low) categories for England. Nitrogen dioxide variation was less extreme for South Lakeland. No discussion of these odd findings and assumptions.

The basic, and undeniable, thesis is that air pollution causes related diseases and consequential premature deaths. Table 7 makes some heroic estimates of the costs of primary, secondary and social care and medication.

Their conclusion (p.49) is:

“Between 2017 and 2025, the total cost to the NHS and Social Care of air pollution in England is estimated to be £1.60 billion for PM2.5[fine particulates] and NO2 [nitrogen dioxide] combined (£1.54 billion for PM2.5 and £60.81 million for NO2) where there is robust evidence for an association between exposure and disease. If we include the costs for diseases where there is less robust evidence for an association, then the estimate is increased to an overall total of £2.81 billion for PM2.5 and £2.75 billion for NO2 in England between 2017 and 2025.”

Curiously, the extension to 2035 comes earlier (p.29):

“From 2017 to 2035 it is predicted that 3,242 cumulative incidence cases per 100,000 population will be attributable to PM2.5 exposure in Lambeth, compared with 861 cases per 100,000 population in South Lakeland and 2,248 per 100,000 population in England. This represents a total NHS and social care cost of £9.41 billion, £80.26 million and £7.45 million per population for England, Lambeth, and South Lakeland respectively.”

One would expect the cost attributed to pollution would be the England level minus the South Lakeland (low) level but this subtraction does not seem to have been made.

Reviewing this paper was hard work as the authors seem to have immersed themselves in detail and failed to address three big picture questions:

The scenarios needed to be compared with a careful consideration of what would have happened without the pollution. People do die of the same diseases, e.g. heart attacks, when pollution is not a factor. And people do die prematurely, notably in the poorer areas of Lambeth, due to relative deprivation. Waiting in winter for London buses is a major health risk.

No attempt was made to disentangle causation from correlation.

It is hard to verify data extrapolated 20 years and no attempt was made to do so.

In short, when government says it is merely following the science: it may be blinding itself or they may just be trying to blind us with nonscience.